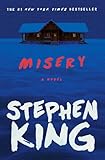

As we learned from Misery, the story of the woman who holds a man captive can never be a glamorous one. Over the course of Stephen King’s 1987 novel, we’re led to understand that Annie’s insanity—her insecurity, her obsession—is inextricable from that which makes her unlovable, a given long before she ever stumbles across the luckless object of her affections, her favorite writer, in the wreckage of his car. Dowdy and deranged, Annie forces him to rewrite his final novel according to her whims, crooning, “I’m your biggest fan,” over his tortured body.

And indeed, what could be beautiful or romantic about a woman with the violent upper hand, the muse forcing herself on the artist—never mind that the gendered inverse (see: Scheherazade’s dilemma) is the stuff of literature? A story about woman holding a man against his will, especially if she seeks to exploit his creative labor…Well, that’s just crazy. And for women, crazy, as we all know, is not a Good Look.

And indeed, what could be beautiful or romantic about a woman with the violent upper hand, the muse forcing herself on the artist—never mind that the gendered inverse (see: Scheherazade’s dilemma) is the stuff of literature? A story about woman holding a man against his will, especially if she seeks to exploit his creative labor…Well, that’s just crazy. And for women, crazy, as we all know, is not a Good Look.

While Glenn Close boasts a career spanning more than 40 years and dozens of awards, including six Oscar nominations, she’s still best-known for her portrayal of Alex, a woman who attempts to murder her married lover in a fugue of jealousy and rage. The story of Alex—otherwise known as 1987’s Fatal Attraction, the film for which Close received one of those six nominations—is one whose histrionics and gendered ableism have brought with it both critique and dismissal in the three decades since its release. And though Close herself has undoubtedly continued to thrive, she also hasn’t been able to escape its shadow.

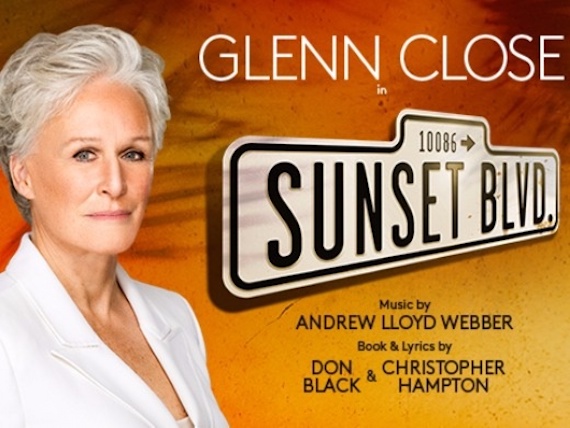

Such a legacy may sound like a curse—but then, Close does crazy so well. This spring, she returned to Broadway to reprise the starring role in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s adaptation of Sunset Boulevard, and she’s as captivating onstage as she is in her best movies. Once more, she takes on Norma Desmond, the silent film actress fixated on her past glory from the shadows of obscurity, still ready for her closeup decades after the world has moved on to talkies (and to younger leading ladies). The plot ignites when Desmond hires screenwriter Joe Gillis to doctor the script that she’s convinced will spell out her big comeback, and though his capture isn’t quite as obvious as the one masterminded by Misery’s Annie, his gradual (co-)dependence on his new benefactress proves to be just as deadly.

Such a legacy may sound like a curse—but then, Close does crazy so well. This spring, she returned to Broadway to reprise the starring role in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s adaptation of Sunset Boulevard, and she’s as captivating onstage as she is in her best movies. Once more, she takes on Norma Desmond, the silent film actress fixated on her past glory from the shadows of obscurity, still ready for her closeup decades after the world has moved on to talkies (and to younger leading ladies). The plot ignites when Desmond hires screenwriter Joe Gillis to doctor the script that she’s convinced will spell out her big comeback, and though his capture isn’t quite as obvious as the one masterminded by Misery’s Annie, his gradual (co-)dependence on his new benefactress proves to be just as deadly.

Since Boulevard’s original film release, the role has become famous for its tragic, hysterical femaleness, and is for that reason vulnerable to one-dimensional renderings of empty, and even harmful, stereotype. But despite this, Close somehow succeeds in recreating a character whose humanity permeates the Palace Theatre, like a furious cloud of gold that envelops audience all the way up to the nosebleeds.

Close is good, almost distractingly so. As an audience member, I spent as much time enjoying the production as I did wondering just how she does it. Is it the suppleness and subtlety of her craft, for which James Lipton once praised her on Inside the Actor’s Studio? Is it the way she injects even the most heartrending of Desmond’s dramatics with narcotic, knowing camp? Is it in the way her presence, as commanding as her voice—its raw power somehow undiminished as the 70-year-old scales countless flights of stairs over the course of the 200-minute show—so masterfully balances bottled panic with profound and searching pain? Whatever the reason, only a seasoned artist could embody the crazy woman, a figure infamous for her unwantedness, without sacrificing an ounce of soul, or a whit of glamour.

Her performance is all the more remarkable considering the fact that humanity is not something the crazy woman is typically afforded, as critics of Fatal Attraction were quick to point out. This archetype, the creation of a society in which a woman who desires (what she doesn’t have; what she shouldn’t want; what is inconvenient or dangerous for male authority) must be institutionalized, silenced, or worse, is deep in the bedrock of our culture. Though Alex and Norma embody slightly different kinds of failed female revolt—the former as a woman professional, the latter as a woman artist—both are in conversation with hysteria, one of the 19th century’s most prevalent (and most gendered) diseases of the West. On film and in subsequent stage adaptations, Boulevard’s subtextual warning that women’s ambition, creativity, and desire for sexual fulfillment are the causes of unhappiness and undoing still comes through loud and clear. After all, the original film, released in 1950, starred a woman who was born in the heyday of Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell, a pioneer in the study of nervous conditions who urged Charlotte Perkins Gilman to treat her hysteria by abstaining from her work as a writer, and to “never touch a pen, brush or pencil,” as long as she lived.

But even in the 21st century, Desmond still exists in the crosshairs of the 20th, an unsettling bridging of contemporary and Victorian gender dynamics. Regardless from which perspective she’s viewed, she’s still forced to star in the spectacle of her own artistic destruction, and as the villain, to boot. Such is her due, for the woman who is too needy (which means she believes she deserves happiness); too self-obsessed (though that same brand of self-obsession is how Boulevard’s Joe aims to fight his way to stardom); or too selfish (another quality that Gillis, played almost dandily by Michael Xavier, can unquestioningly deploy), no success goes unpunished.

More revealing than the spectacle of the crazy woman are the ebbs and flows of her presence in popular culture. At the moment, the cynical rehashing of old classics and dreamscapes for new entertainment is all the rage. One of the most prominent characteristics of the so-called Golden Age of Television is its mobilization of nostalgia, exhuming artists overlooked or misunderstood because of their gender (as well as other identities; nothing, least of all the crazy woman archetype, is untouched by the ravages of white supremacy). Slowly but surely, we’re beginning to revisit geniuses once dismissed as too narcissistic (Nina Simone), mercenary (Joan Crawford and Bette Davis), or selfish (Eartha Kitt) to be taken seriously. Though an incredible boon to the viewers of our time, none of this, of course, does Desmond, and the dead women she represents, any good: After all, it was the unforgivable sin of insanity, and not her own artistry, that garnered her a place in the celluloid pantheon.

The spectacle of female humanity was recently addressed by Jess Zimmerman in her brilliant Role Monsters series with an essay on the rapacious, relentless harpy. “In isolation,” writes Zimmerman, “female ambition is laudable, the kind of thing asset management firms make statues about. In context, it’s considered monstrous.” Even now, at a time when American women can ascribe to feminism with comparatively little fanfare, insisting on one’s own humanity as a woman is still an act of monstrosity—one with which ugliness and craziness, the two things that women are supposed to fear most, is always elided.

With Sunset Boulevard, Close returns to the stage at a time in which women and non-cis-male people across demographics are watching a reinvigorated assault on hard-won rights and liberties. While the monstrosities of misogyny and sexism play out in daily life, her embodiment of a woman made monstrous by her desire for better feels a lot like bearing witness. Curse though it may be, it’s also Close’s most beautiful legacy.