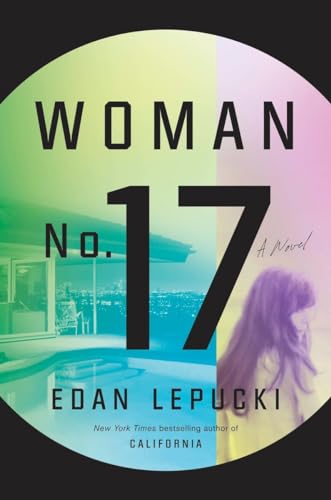

Edan Lepucki’s Woman No. 17 is the story of Lady, a mother of two recently separated from her husband, Karl. She hires a nanny named S to watch her toddler son while she works on a memoir about raising her teenage son, Seth, who can’t speak. S, who until recently went by Esther, has decided to start acting as she thinks her impulsive, hard-drinking mother would, as an act of performance art. As Lady feels the growing distance from her sons, she becomes close to S, who herself is warming to her put-on personality and finding a friend in Seth. Got that?

Lepucki and I are both staff writers for The Millions. We have collaborated before on pieces about Gillian Flynn and Tana French (both of whom come up in this interview) and casting a Goldfinch movie. I was thrilled to read her insightful, funny, sometimes unsettling book, and get to ask her about it.

We talked about eyebrows and makeup, performing gender and trying to control one’s narrative, secret online lives, and characters with dual identities.

The Millions: It seems to me like in the last few years beauty rituals have come out of the closet. Rather than just taking orders from women’s magazines, we’re all talking about what we do to ourselves to look the way we do. I know you and I are both big fans of the “Beauty Uniform” column on Cup of Jo, and I noticed in the book a lot of the characters describing their beauty rituals, or noticing other people’s. Why do you think we’ve become so upfront about it, and why did you want that in the book?

Edan Lepucki: I like that this is the first question. Well I’ll say first I’ve always been really open about that kind of stuff in my life. It’s easy for me to be naked with people and talk about my body. I think the human body’s really funny. I’ve always gravitated to the other girls and women who are also like that. I’ve always been kind of shocked when someone doesn’t want to communicate about that kind of stuff. I personally find it really fun to share — I color my hair, get my eyebrows down — I think it’s fun to talk about that.

In my book, it’s not like I set out to do that, but I also really wanted to write a book that felt exceptionally contemporary. There’s one point when Lady on Twitter talks about getting a Brazilian. When I thought of it I was so pleased by it but also really embarrassed. It’s so private and ridiculous, but if I put it in the book it feels courageous in this absurd way. One way to make the book feel contemporary was to talk about those things that are super private that are becoming more and more public. The whole book, too, is about representation and the masks we wear and the performance of our identity in all these ways, and obviously that includes gender and the ways that we put on ourselves and put on our femininity, and I wanted to show that.

TM: I sort of think women got to the point where they thought, if I’m gonna go through all this and spend 20 minutes on makeup every morning and have all these expensive appointments, I want you to know why I’m doing it, or that I’m making intelligent decisions about it. People love explaining to you why their products work for them, and by talking about it we’re refusing to let it be trivialized. There’s a line in the book where you say being a woman is a lifelong education, and it’s like it takes so long to get good at this stuff, that once you have a handle on what your beauty identity is going to be, you’re so proud of it.

EL: I think it is a badge of honor. I also think that when I document any beauty rituals I’m saying I’m aware that I’m spending three hours to work on my hair, and the awareness of that oppression sort of liberates me. I’m comfortable with the burdens of my gender.

TM: Lady is also frequently giving spontaneous advice to S about grooming, and thinking about the advice her mom gave her. Like talking about beauty rituals is an intimate form of female communication.

EL: I think one of the main qualities of Lady is that she is carrying a lot of resentment towards her mother. She believes her mother damaged her, and she’s carrying that damage into all her other relationships. She’s sort of playing out the same relationship with S that she had with her mother, so I was really interested in how she’s repeating those cycles. It’s sort of the only way she knows how to be. She’s totally barred, she won’t really let anyone in, and at the same time she’s critical of everyone else. It’s especially heightened with other women, because she lived with a mother who criticized.

TM: The main reason I’m obsessed with the performative femininity in the book is that Lady and S and Kit (Lady’s sister-in-law) all ostensibly have artistic projects that they’re focused on, and this is what they would tell you is their work, but in Lady and S’s cases it’s faltering. Meanwhile how they’re performing their womanhood is speaking so much more loudly. They’re trying to express themselves through these specific projects, but they’re really expressing themselves so much more clearly through the roles they play.

EL: I think you’re right. Lady in particular — her artistic project is a story of her motherhood, and it’s a story of connection and triumph, and it’s not the narrative that is true. It makes sense that the way that she’s actually coming through is not through that story, but through every day you see in the novel. Her story is really everything she’s trying to avoid.

S is interesting because the question for me while I was writing was “who is S?” She’s so young and it allows her to be really reckless in what she does and she’s not fully formed, she’s like a ball of clay. At the beginning of the book she talks about how she’s a girly girl, but you never see that in the novel. She’s very ordered in her life, and then she tries to enact her mother’s version of motherhood, which, besides being drunk all the time, means that she doesn’t wear make up and doesn’t care what people think. As I was writing I realized that there were a lot of ways in which S wanted to be like her mother — these qualities that she did not have herself — and by becoming her mother she was able to become this different kind of woman, one who can say what she means, the first thing on her mind, and I think she gets a thrill from that. I don’t know if the disconnect between who she is and who she’s playing is causing a tension in her.

TM: This is something I also ask authors who have a character who’s very secretive or is hiding something. With S, most of the time she’s a person pretending to be a different kind of person. It’s like in movies where somebody is acting like they’re a bad actor. As the author, how well do you have to know Esther, S’s “natural self,” before you can layer S on top of her?

EL: It’s a similar question to how do you write a repressed character — how do you write a character who is unable to think certain things when you as the author know what’s motivating them. Esther to me was really slippery, as she is in the book. I have a real sort of love for her. Her core for me is a real longing — firstly, for her to have something with her mother that she doesn’t have. Immediately I could feel that from her. And secondly her heartbreak — what really sets her off on this whole thing is that she’s getting over her dumb boyfriend. Describing her boyfriend Everett’s art projects, I could feel S — even if she was writing them off — I could tell that she really admired Everett. That also felt very true to her. And her relationship to her father — every time she was talking to her dad, immediately I could lock in to S. But at other moments I was like, there isn’t a real S. I did reread The Talented Mr. Ripley, which is a book I love, because I wanted to read those moments when Tom Ripley becomes Dickie Greenleaf, and those moments when he locks into the next persona. I love those descriptions and I used them as a model. There is a blankness to S, but part of me thinks that’s just because she’s so young. Is part of that because her parents are divorced and don’t communicate and are so different that she’s had to be two different people already? That’s something that I identify with personally. My parents divorced before I was 5 and I went from one house to the next and they never spoke to each other, and I really did have two different lives with them, so I wonder what part of that slipperiness or blankness of her will always be there. I do think there’s a vulnerability to her that I sort of get, and maybe that makes me more compassionate to her than other people.

EL: It’s a similar question to how do you write a repressed character — how do you write a character who is unable to think certain things when you as the author know what’s motivating them. Esther to me was really slippery, as she is in the book. I have a real sort of love for her. Her core for me is a real longing — firstly, for her to have something with her mother that she doesn’t have. Immediately I could feel that from her. And secondly her heartbreak — what really sets her off on this whole thing is that she’s getting over her dumb boyfriend. Describing her boyfriend Everett’s art projects, I could feel S — even if she was writing them off — I could tell that she really admired Everett. That also felt very true to her. And her relationship to her father — every time she was talking to her dad, immediately I could lock in to S. But at other moments I was like, there isn’t a real S. I did reread The Talented Mr. Ripley, which is a book I love, because I wanted to read those moments when Tom Ripley becomes Dickie Greenleaf, and those moments when he locks into the next persona. I love those descriptions and I used them as a model. There is a blankness to S, but part of me thinks that’s just because she’s so young. Is part of that because her parents are divorced and don’t communicate and are so different that she’s had to be two different people already? That’s something that I identify with personally. My parents divorced before I was 5 and I went from one house to the next and they never spoke to each other, and I really did have two different lives with them, so I wonder what part of that slipperiness or blankness of her will always be there. I do think there’s a vulnerability to her that I sort of get, and maybe that makes me more compassionate to her than other people.

TM: The characters in the book are frequently expressing themselves in different modes. With Seth it’s so literal because speech is a form of expression that’s cut off from him, and so he gets so good at communicating with facial expressions or condensing a conversation into three sentences. Do you feel like everybody in the book is doing that in their own way? Nobody else has an avenue cut off from them in such a literal way, but they’re finding ways around what they’re unable to communicate.

EL: When you’re writing a book, you don’t know what you’re doing. I personally try to avoid any understanding of the themes of the book until I’m done, but then you stop and go, oh I see, the whole book is about communication and representation, feinting and dodging. Seth is such a literal version of that, he cannot speak so he has to express himself in these very specific ways. He can’t communicate and yet he’s so adept at communicating, whereas other people can talk and talk and not say anything that’s really true.

Somebody who read the book pointed out that everybody is using either art of the Internet to either hide or emerge. Lady is definitely hiding in her memoir, yet weirdly with @muffinbuffin41 (her Twitter handle) she’s kind of emerging. There’s this sneaky self of hers that’s true that’s online. Esther is literally hiding behind S, but there are moments when she doesn’t know if it’s S or Esther who’s feeling something, so the attraction to Seth is really fraught because she knows she’s crossing a boundary, but she knows her mother would be really into it. Everyone is either jumping right into something — whether a photograph or the Internet — or they’re completely using that to shield themselves. The trick is to figure out when they’re being real and when they aren’t.

TM: As soon as she decided to have a secret Twitter account, I was like, oh no that never works.

EL: [Laughs.] Do you speak from experience, Janet?

TM: Not personally, but in college we found a teammate’s secret LiveJournal, which she used to talk about all of us. A secret Twitter account is like a gun in the first act, somebody’s reading it by the end of the book. But what was Lady’s motivation to start a secret Twitter — is it as simple as being lonely?

EL: When I was done writing California, I was like, the next book I write is going to have technology. I want to have technology be a part of not only the everyday life of the characters, but be thematically important. My goal was to have it be part of the plot. If I was going to have Twitter in the novel, things had to be revealed in Twitter. There’s so many novels that take place in the ’90s because nobody wants to deal with the Internet issue. It’s hard to write anticipation and romance and spontaneity with the Internet. I thought, I need to put this into my novel and use it to the benefit, like how does the Internet amplify all our issues, and make things more suspenseful? And one of those ways is making your Internet presence a secret.

EL: When I was done writing California, I was like, the next book I write is going to have technology. I want to have technology be a part of not only the everyday life of the characters, but be thematically important. My goal was to have it be part of the plot. If I was going to have Twitter in the novel, things had to be revealed in Twitter. There’s so many novels that take place in the ’90s because nobody wants to deal with the Internet issue. It’s hard to write anticipation and romance and spontaneity with the Internet. I thought, I need to put this into my novel and use it to the benefit, like how does the Internet amplify all our issues, and make things more suspenseful? And one of those ways is making your Internet presence a secret.

TM: Seth is diagnosed with selective mutism. Is that a common condition?

EL: It’s not a perfect diagnosis. I once read Gillian Flynn or Tana French talking about doing research with homicide detectives, and she said, I don’t need this to be common, it just has to be plausible. That’s sort of how I thought about Seth’s disability. In my story he just doesn’t speak, that’s the end of it. The way he has it, I don’t know if it’s possible. I wanted to emphasize his humanity in all ways while also emphasizing that there is something he cannot do and that affects his life. I didn’t want to be like it’s not a big deal, and I also didn’t want to make him only his disability. As he tells S, he’s not a metaphor. I wanted to make him a full human character. That was one of the biggest struggles of the book: how do you write Seth? How do you write a scene with someone who doesn’t speak, how do you write dialogue with someone who doesn’t speak? How do you look head on at disability and also recognize that its not his story, it’s two people who don’t have his disability talking about his disability? So they’re going to get things wrong, they’re not going to represent him properly, they’re not going to see him full at all points. The failures of that was what I was interested in.

TM: Your first book was titled California, but this book is also definitely a California novel.

EL: It was such a relief to be able to describe the world as it is now. I had not been able to do that for years when I was working on California (a post-apocalyptic novel). It was almost as if I had been writing a sestina for a long time and then suddenly I got to write free verse again. I didn’t feel constrained, there was no speculation going on. I just got to look outside and describe what I see.