1.

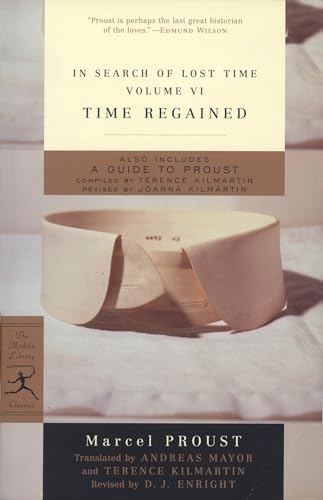

Several months ago, a commenter asked if reading Marcel Proust had affected my writing, and I’ve been turning the question over in my mind ever since. I thought it would make an interesting subject for a book club entry, and I’ve started this one many times, but I haven’t been able to write anything. One reason is that I’ve been working on a novel, and that’s taking up a lot of my time. A second reason is that my attention (like everyone else’s) has been dragged this way and that by the news cycle. A third reason is that the final volume, Time Regained, is so intelligent, so truthful, and so piercing, that there doesn’t seem to be any point in writing about it. I have nothing to add, nothing to analyze. There is also something incredibly delicate about this last volume. The narrative seems to be crumbling in my hands. The characters are suddenly much older, World War I has arrived, and the voice of the author is, for the first time, a little rushed. You can tell Proust is dying, truly writing on deadline, and it’s as if the book’s most important theme, Time, is taking over.

(I have more to say on Proust’s treatment of death, but I don’t think I can write it until I’ve finished the book.)

With 200-odd pages still left to go, it feels too early to reflect on how this past year of reading has affected my writing, in general. But I can speak to how Proust has aided me in my own fiction. In particular, reading In Search of Lost Time has helped me to refine my approach to characterization.

With 200-odd pages still left to go, it feels too early to reflect on how this past year of reading has affected my writing, in general. But I can speak to how Proust has aided me in my own fiction. In particular, reading In Search of Lost Time has helped me to refine my approach to characterization.

The novel I’m working on now is almost completely character driven, and the premise is simple: here are three women on the brink of three different life changes; let’s see how they fare over the next five years. When I started making notes for this book, a few years ago, I wasn’t sure what these three women would do or if I even had a book. (To be honest, sometimes I’m still not sure, but that’s a topic for another day.) Small plots have emerged, but most of my technical focus has been on characterization. I want to keep showing different aspects of each woman, while at the same time giving the reader a consistent sense of who each character is and how she will behave. To put it more simply, I want readers to feel as if they know these characters, in a real, complex way.

2.

My first — and now that I think about it — only formal lesson in characterization came from my 10th-grade creative writing teacher. He asked our class to come up with a list of ways that authors convey character without simply describing a person’s personal qualities, e.g. “kind,” “greedy,” “selfish,” “compassionate,” etc. First on the list were physical description, action, and dialogue. From there we moved to the environment that a character inhabits, and their social milieu: their family and friends; their clothing and possessions; their house, room, office, school, etc. Then we got into the more subtle aspects of physical presence: the sound of a voice, a manner of sitting or standing, particular movements or gestures. Finally, we considered a person’s inner, unseen qualities: their thoughts and beliefs, likes and dislikes, loves and hates, and their previous lived experiences, i.e. their “backstory.”

This may seem like a blindingly obvious exercise, and maybe it was (we were 15), but as I recall, we got into a big discussion of personality and some students questioned the premise of the exercise. Why couldn’t you just describe a character as “nice” or “good” and get on with the story? Why did you have to show it? My teacher told us that it’s more memorable for a reader to decide that a person is nice, rather than being informed of their niceness. But he offered the following work-around: another character could say that a character was nice, and that would also be memorable — though of course, character’s B’s testimony of character A’s niceness would be judged based on a variety of factors, including but not limited to: character B’s relationship to character A, character B’s motivations with regard to A, character B’s overall trustworthiness, and to whom character B is describing character A’s niceness.

This is the part of the lesson that really stuck with me, because it made me see, first of all, how plot can arise from character. Even in this highly abstract set-up, you can’t help wondering if character A is really as nice as character B says. At the same time, it made me see how difficult it is to represent the intricacies of human interaction. What is said and what is done isn’t even half of the equation. We have a variety of social selves, and even the most straight-shooting, guileless person speaks differently to a parent than to a best friend. To properly reveal a character, you would need to show them in a variety of situations and moods and how on earth are you supposed to do that with any economy?

One answer is: don’t write a novel. Instead, write something for the stage or screen and let the actors fill in all the subtle dynamics that action and dialogue alone cannot describe. Another answer: write a long novel or a series of novels with the same characters. It’s human nature to feel attached to the people we spend the most time with — this is basically the premise of the American version of The Office — and so even if the characterization is not subtle, you can’t help feeling close to a person you have followed for thousands of pages over the course of several books.

At first blush, it would seem that Proust’s strategy is to write a very long book. The events of In Search of Lost Time take place over four decades. Characters grow up, marry, and bear children. Some become ill and die. This accumulation of events certainly contributes to a feeling of knowledge and intimacy. But the key to Proust’s characterization is, paradoxically, the way he shows that, when it comes to other people, there is no knowledge and no real intimacy. Our experience of other people is subjective, colored by our own fantasies and projections or dulled by habitual contact. As Proust observes in The Fugitive, at the end of his long, tormented affair with Albertine: “It is the tragedy of other people that they are merely showcases for the very perishable collections of one’s own mind.” Our subjective assumptions keep us ignorant of other people’s motives and proclivities, and certainly we know little of the inner changes taking place in other people. In addition, powerful outside forces are constantly shaping people in ways in which they themselves are often unaware: history, society, time — to name a few. Throughout In Search of Lost Time, Proust illustrates this ambiguity by revealing new sides to his characters. The final chapter of The Fugitive is straightforwardly titled: “New Aspect of Robert de Saint-Loup.”

At first blush, it would seem that Proust’s strategy is to write a very long book. The events of In Search of Lost Time take place over four decades. Characters grow up, marry, and bear children. Some become ill and die. This accumulation of events certainly contributes to a feeling of knowledge and intimacy. But the key to Proust’s characterization is, paradoxically, the way he shows that, when it comes to other people, there is no knowledge and no real intimacy. Our experience of other people is subjective, colored by our own fantasies and projections or dulled by habitual contact. As Proust observes in The Fugitive, at the end of his long, tormented affair with Albertine: “It is the tragedy of other people that they are merely showcases for the very perishable collections of one’s own mind.” Our subjective assumptions keep us ignorant of other people’s motives and proclivities, and certainly we know little of the inner changes taking place in other people. In addition, powerful outside forces are constantly shaping people in ways in which they themselves are often unaware: history, society, time — to name a few. Throughout In Search of Lost Time, Proust illustrates this ambiguity by revealing new sides to his characters. The final chapter of The Fugitive is straightforwardly titled: “New Aspect of Robert de Saint-Loup.”

3.

The character twist is a staple of thrillers, but Proust does not use character revelations to advance his plot (the plot of In Search of Lost Time, if there can be said to be one, is: how Proust came to write In Search of Lost Time). Instead he uses them to remind the reader that our observations of other people are subjective and incomplete. Here’s Marcel, in a scene from The Captive, reflecting on the unexpected kindness of an old family friend, a person who had generally been indifferent toward him:

The character twist is a staple of thrillers, but Proust does not use character revelations to advance his plot (the plot of In Search of Lost Time, if there can be said to be one, is: how Proust came to write In Search of Lost Time). Instead he uses them to remind the reader that our observations of other people are subjective and incomplete. Here’s Marcel, in a scene from The Captive, reflecting on the unexpected kindness of an old family friend, a person who had generally been indifferent toward him:

I concluded that it is as difficult to present a fixed image of a character as of societies and passions. For a character alters no less than they do, and if one tries to take a snapshot of what is relatively immutable in it, one finds it presenting a succession of different aspects (implying that it is incapable of keeping still but keeps moving) to the disconcerted lens.

Proust illustrates this “succession of different aspects” in a beautiful passage about Saint-Loup, one of the most well-developed characters in the novel, someone we see throughout the book and feel that we know. But after Saint-Loup’s death, it occurs to Marcel that he really didn’t know his friend very well, and that they rarely saw each another:

And the fact that I had seen him really so little but against such varied backgrounds, in circumstances so diverse and separated by so many intervals — in that hall at Balbec, in the café at Rivebelle, in the cavalry barracks and at the military dinners in Doncieres, at the theatre where he had slapped the face of the journalist, in the house of the Princesse de Guermantes — only had the effect of giving me, of his life, pictures more striking and more sharply defined and of his death a grief more lucid than we are likely to have in the case of people whom we have loved more, but with whom our association has been so nearly continuous that the image we retain of them is no more than a sort of vague average between an infinity of imperceptibly different images and our affection, satiated, has not, as with those whom we have seen only for brief moments, during meetings prematurely ended against their wish and ours, the illusion that there was possible between us a still greater affection of which circumstances alone have defrauded us.

To me, this paragraph is a miniature class on literary characterization. Marcel is saying that even though he does not actually know Saint-Loup very well, he feels that he does; there is an illusion at play. And that illusion is the result of having seen Saint-Loup for brief periods of time in a variety of different circumstances. Anyone who has ever been in a long-distance relationship will certainly recognize this phenomenon. A dear friend recently visited me, or at least someone I consider a dear friend, though I have actually not spent much time with him. We have never lived in the same city and I know very little of his daily life. But we see each other every year or so, and I remember our meetings in greater detail than I do with friends in New York that I see on a regular basis. In some ways, this friend is more real to me than my friends who are “like family” — the ones I text with daily and who wipe my child’s nose. I rely on my local friends for companionship and community but I don’t notice them in quite the same way.

Literary characters are, maybe, like long distance friends. Your perception of them is brief, but intense. Even in a very long book, an author writes with the knowledge that there is a limit to the number of scenes he can write with a particular character, or the number of lines he can devote to physical description or psychological observation. An author is not trying to reconstitute an actual person, but to create an illusion of intimacy. And there are tricks — many of them as described by my teacher, earlier in this entry. But the main trick is to abandon objectivity. That doesn’t mean that a novelist has to employ a subjective narrator. It’s not the mode of narration that matters, it’s the discipline of the author — the precision it takes to leave aspects of a character unresolved and ambiguous.

4.

In order to exert some discipline on this essay, I will not get into Proust’s philosophy of selfhood, which distinguishes between the parade of moods, states of mind, and social performances that constitute our experience, and a deeper, bedrock self. But in terms of literary expression, of trying to create the illusion of character, one thing I’ve learned from reading Proust is that a writer must attempt to show a character’s “succession of selves.” This is different from the classic storytelling advice: that a character must change or grow over the course of the narrative. I’ve never liked that presumed moral arc; it feels constraining and didactic. Also, it’s not necessary, because the passage of time will always reveal character.

The poignancy of the final volume, Time Regained, is in seeing all of Proust’s character’s age. At a party attended by many of the novel’s personages, Marcel observes that he must study the guests with his memory as well as with his eyes. Some are so transformed that he doesn’t recognize them at first. Of his old school friend, Bloch, Marcel cannot even perceive him as middle-aged until someone else points it out:

I heard someone say that he quite looked his age, and I was astonished to observe on his face some of those signs which are indeed characteristic of men who are old. Then I understood that this was because he was in fact old and that adolescents who survive for a sufficient number of years are the material out of which life makes old men.

In Time Regained, the chronology is somewhat confusing as War World I begins and ends, Marcel retreats to a sanatorium for an unspecified number of years, and certain marriages are never fully explained. It’s hard to know if this was intentional, since Proust never had a chance to complete his revisions, but it makes psychological sense, because time doesn’t pass logically for us, especially when it comes to our friends. By embracing the subjectivity of perception, and of the passage of time, Proust created characters that feel as mysterious, fleeting, and precious as life itself.