Within a month and a half, both Lydia Davis and Jhumpa Lahiri published essays on their efforts at learning a new language. Their reasons and methods couldn’t have been more different, yet underneath their distinct approaches runs a commonality that unites them in a common act. It’s the same commonality that links together every reader of literature, present and past.

Lydia Davis’s essay, “On Learning Norwegian,” was included in the first volume of John Freeman’s biannual anthology. Davis had a rather bizarre compulsion to read Dag Solstad’s “Telemark novel.” There is almost no chance that it will ever be translated into English. It will be a miracle if more than five Norwegians even read it. To call the book a novel is to bend that word to the limit. There are fierce debates in Norway over Solstad’s use of this term to describe to his newest project.

The “Telemark novel” is long — 426 pages not counting the appendix. It is devoid of any action or drama. There is no unifying plot. It is a recitation of Solstad’s ancestors who lived in the town of Telemark from 1691 to 1896. Accounts of their births, deaths, marriages, and property transactions. And little else. Why Davis was moved to read this book, I’m not sure and neither is she. It has less to do with the novel itself and more with Davis’s desire for experiment.

Davis did not know Norwegian. And she knew that it’s almost inconceivable that the novel would ever be translated into a language she could access. So why not just learn Norwegian? Reading Solstad would be a rewarding challenge in itself. The act would not accomplish anything, per se. There is no joy to be had in following a great storyline or new knowledge to learn about the universe. The only delight Davis would receive from reading Solstad is being the only non-Norwegian to have done it. But how? That’s the part Davis wants to experiment with.

Davis thought it would be even more challenging to read the “Telemark novel” without using a dictionary and without formal language training. This isn’t as ludicrous as it sounds. Davis already knew German and French so right off the bat she was able to discern certain things — verb conjugation patterns, cognates, the alphabet and its sounds, and some prepositions. And there are advantages to not using a dictionary.

Dictionaries can be detrimental crutches for those learning a new language. They are psychological hindrances to fully grasping vocabulary. If you know that a dictionary is only a keystroke away, you’ll likely not spend as much effort driving new words into your head as you would if you had no safety net. Furthermore, discovering words in context gives a deeper understanding than scanning an abstract definition.

Davis created her own treatments of the Norwegian language. She worked from the inside out. Whenever Davis would divine a term’s import she would add it to a running list. Each time she’d crack open a syntactical feature she’d include it in her nascent grammar. She did cheat a few times. She had a handful of sessions with a language teacher and she read through a children’s book and a graphic novel to acquire a basic vocabulary. But other than she taught herself Norwegian by reading one of the most opaque “novels” to ever be published in any language.

She is open about the fact there was much in the book she didn’t understand. But going through it slowly, reading it word by word, opened to her new ways of thinking. She learned almost as much about the English language as she did the Norwegian. Most of these discoveries were etymological but often they would lead to more philosophical observations. Davis learned that “neighbor” means to live near someone. She mused that this could be good or bad, depending upon the persons involved. She also noticed characteristics about Solstad’s writing that she might not have understood if she were reading fast. Solstad shifts his narrative mode to explain the same event in a different way and his writing changes pace to reflect the nature of the narrative. These insights are fairly minor but they were products of hard-fought work so to Davis they were grand accomplishments.

Davis did not become fluent in Norwegian. She is not able to speak it nor can she readily compose Norwegian prose. She was able to understand a good bit of a tremendously challenging tome without recourse to learning aids. A herculean task if there ever was one.

Jhumpa Lahiri did precisely the opposite of Lydia Davis. In “Teach Yourself Italian” published in The New Yorker, Lahiri describes how she availed herself of every tool imaginable to learn her language of choice. She bought textbooks, met with tutors for years on end, and finally moved her family to Rome. It took her years and years of frustrating toil but she finally reached the point where she was satisfied with her efforts. Most impressive to me was the fact that her essay was translated into English by Ann Goldstein. Lahiri wrote it in Italian.

Lahiri explores more deeply than Davis her reasons for learning a new language. For here it wasn’t a merely a fun challenge. Lahiri’s mother was born in India and she raised Jhumpa speaking Bengali. But Lahiri admits that her command of Bengali is far from perfect. She can’t write in it. Nor can she speak it without an accent. She feels alienated from her mother tongue. But English, her default language, is actually her second language. She feels like a linguistic exile, an author without a home.

Lahiri wanted to get away from English, to find rest and transformation in a language new and different. She reconstructed herself from the grammatical ground up. Lahiri wanted to connect with another way of viewing the world and fuse it with her own. Davis and Lahiri are similar in this. Why else would Davis spend an entire year reading a single book? She wanted to grow, to change, to metamorphose through the challenge. She also desired a connection with this very alien way of telling a story, to see the world through Solstad’s eyes.

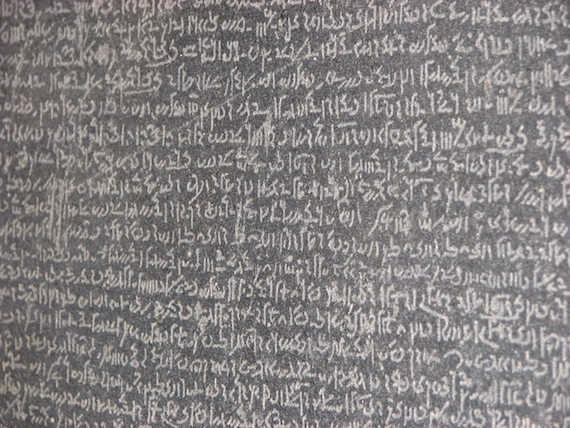

Davis and Lahiri’s narratives remind me of the first author that we know of in human history—a Mesopotamian princess who went by the name Enheduanna. We don’t know exactly how Enheduanna learned the language she wrote, but we can surmise that she probably did it through a hybrid of Davis’ and Lahiri’s approaches.

Roughly 4,500 years ago, Enheduanna’s father united two cultural groups of Mesopotamia into a single empire. These two areas spoke different languages and thought of themselves as different peoples. Enheduanna grew up speaking Akkadian, but after her father conquered the southern lands and joined them to his kingdom, he sent his daughter to become the high priestess at one of this region’s most significant temples. While she was there, Enheduanna learned their dominant language, Sumerian.

Likely, Enheduanna had teachers and, like Lahiri, she also made use of textbooks. Also like Lahiri, Enheduanna moved to the Rome of her day — she traveled to a foreign place where people lived and spoke differently, a place with a reputation as a cultural and religious capital. But like Davis she probably relied on word lists to acquire vocabulary. Enheduanna did not use a dictionary as we understand them. Also like Davis she learned grammar inductively, through reading instead of by memorizing rules of syntax.

Enheduanna also had a similar goal in learning this new language. She produced the first collection of poetry that is known to exist. She rounded up 42 temple hymns that celebrated various shrines across her father’s empire. She included religious sites from both the north and the south. These regions had an open and longstanding hostility toward one another. Enheduanna wanted the residents of the two parts of the new country to understand the commonalities they shared. They had different customs and they spoke different languages but by reading each other’s poems they could bridge these divides, they could meet a new people and come to know themselves in a fresh way.

Lydia Davis came to a realization after she finished Solstad’s book: “It also occurred to me, as I bent over my thin pencil scratches on the handsome pages of the book, that we read selfishly — and we read in whatever way we choose.” I think this is true for the way that most every human reads and has read. We like different types of books; some stories resonate with us while others do not. Davis’s observation is even true for the way we learn languages. People learn in different ways. But the why of reading? I think that, in large part, is something we all share. We’ve been searching texts for a connection to another person or community for more than 4,000 years. This is what Davis and Lahiri wanted. It’s what Enheduanna tried to create. It is likely the reason why you are reading this right now. And in this desire for connection, every reader, across time and place, is intimately linked.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.