With the news of Simon & Schuster’s conservative Threshold imprint acquiring — via $250,000 advance — a memoir by “that person” (whom I’m declining to name, or even describe, because why give him more free publicity?), the outcry was swift, accusing Simon & Schuster of cynically capitalizing on and rewarding hate speech and normalizing white supremacy.

I don’t disagree with those sentiments, but I didn’t jump into the fray because, quite honestly, I didn’t know how I felt. There are a lot of issues at play: hate, misogyny, capitalism (i.e., publishing as a business), coexisting with my reality as a writer fortunate enough to have a supportive publisher. And that publisher is Simon & Schuster.

I had an 800-page manuscript that I had taken 10 years to finish; literary fiction is never a clear moneymaker, long novels are problematic from, if anything, a production point of view (all that paper, all that ink, the increased shipping costs), and yet my editor took me on for a nice five, not six-figure, advance. Even better, she had also just taken on a prizewinning Korean American author whom I admired, whose first book had also come out with an independent press. My editing process at Beacon Press was fairly straightforward because the novel was ready to go. With the current novel, there are structural issues, and a team of editors have rolled up their sleeves, put the tome on a metaphorical lift, and gotten just as sweaty and dirty tinkering with its guts as I have. I’m relieved that, even as the years slide by, they talk only about getting the book right, rather than pushing out “product.” In short, I’m living a dream I’d had as a child banging out stories on my hand-me-down typewriter and selling them — to my parents.

Like many, I was horrified that a person who Twitter had deemed so odious/dangerous it banned him from the platform was being given another platform, a paid one, in short order.

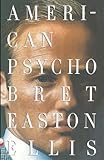

Protest is often the only way to get a company’s attention. And it can have results. But it’s not always the results that were intended, or wanted. For instance, after the outcry over the “sadistic contents” of Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, three months before the book’s publication, it was dropped by the publishing house….Simon & Schuster. CEO Richard Snyder explained, “It was an error of judgment to put our name on a book of such questionable taste.”

Protest is often the only way to get a company’s attention. And it can have results. But it’s not always the results that were intended, or wanted. For instance, after the outcry over the “sadistic contents” of Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, three months before the book’s publication, it was dropped by the publishing house….Simon & Schuster. CEO Richard Snyder explained, “It was an error of judgment to put our name on a book of such questionable taste.”

But the book was just as quickly picked up by esteemed editor Sonny Mehta and published by Random House’s prestigious Vintage imprint.

Irrespective of the nature and quality of these two books, it’s instructive to examine these unintended consequences. Books are indeed published by corporations, which need to sell to stay in business. But as much was we like to treat books as “widgets,” they aren’t interchangeable goods or services. Each one is written by an author or co-author.

In an overcrowded publishing market, bad attention can be just as valuable, perhaps more so, as good attention. The brouhaha over American Psycho certainly branded it into America’s cultural consciousness; the book is still robustly with us, it recently turned 25 and just appeared on Broadway as a musical (!), i.e., trying to kill it with bad publicity may have done exactly the opposite.

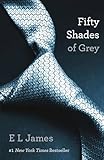

The second thing to consider is unintended collateral damage. Many people objected to the content of Fifty Shades of Grey, but it not only helped keep Random House (now Penguin Random House) in the black, it brought in so much revenue that every employee, from “top editors to warehouse workers,” received a $5,000 bonus.

The second thing to consider is unintended collateral damage. Many people objected to the content of Fifty Shades of Grey, but it not only helped keep Random House (now Penguin Random House) in the black, it brought in so much revenue that every employee, from “top editors to warehouse workers,” received a $5,000 bonus.

So what’s the opposite of a rising tide?

When I heard the calls to boycott Simon & Schuster, that reviewers were going to refuse to review, authors were vowing not to blurb S&S authors’ books, a bookstore tweeted that it wasn’t even going to stock any S&S books, I felt a bit of a chill. I had no urge to write my editors, because they had zero to do with the decision to acquire that book. Publishing firms are “houses” with huge family trees, divided into specialized groups called imprints. While imprints are not wholly autonomous, they each have their own eco-systems. I write literary fiction and publish with the Simon & Schuster imprint. Simon & Schuster also has several other general interest imprints, specialized imprints, and several children’s book imprints, as well as Howard Books, which publishes for the Christian marketplace. Should its Folger Shakespeare Library imprint be penalized for an acquisition by Threshold Editions, a conservative writers’ imprint (that has also published Donald Trump and bona fide war criminal Dick Cheney — with no outcry)?

The calls to boycott are continuing after Simon & Schuster (the company) has stated it intends to go ahead and publish the book in question. So what, then, is the endgame?

Professor Matthew Garcia, who wrote From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement and who has studied boycotts for years told me that “The boycott of S&S will be tricky. It requires a campaign and a set of goals. First, is there an organization willing to put the time in to organize and pursue the campaign the way the United Farm Workers did?”

Professor Matthew Garcia, who wrote From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement and who has studied boycotts for years told me that “The boycott of S&S will be tricky. It requires a campaign and a set of goals. First, is there an organization willing to put the time in to organize and pursue the campaign the way the United Farm Workers did?”

Good question. I personally feel that protecting healthcare, especially Medicaid and Medicare, is one of the most important things we need to do right now.

“Second, that organization needs to do what UFW did with grapes — identify what percentage of the product’s delivery to market they need to effect in order to have S&S respond,” Garcia said. “In the UFW case, they did not hit all sellers of grapes equally. They targeted the biggest sellers, and set as their goal to reduce sales by 10 percent in 10 of the top markets. They did that by knowing what amount would hurt their bottom line, and produce the biggest seller’s capitulation. I imagine the organization that pursues a boycott of S&S would have to identify the same profit margins for the company and what it would take to tip them in order to identify effective goals.”

Books, though, aren’t an undifferentiated product like grapes. There’s a lot of untethered anger that’s much more than about one guy, one book deal, one company. People are mad as hell (rightly so) about the rise of the so-called “alt-right” (a.k.a. white supremacists). But how do we try to harness this anger productively? Successfully boycotting S&S is not going achieve what many of us really want — which is to boycott 2016.

But if we’re going to try to get Simon & Schuster (and CBS, its parent company) to listen, what books should boycotters target to get to the United Farmworkers’ 10 percent threshold? Probably the big ones like…the Bruce Springsteen memoir. Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer-winning novel, All the Light We Cannot See. Maybe Shonda Rhimes’s bestselling memoir, Stephen King’s latest? How about Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything — cited as one of the “Seven Books You Need to Understand (and Fight) the Age of Trump“?

But if we’re going to try to get Simon & Schuster (and CBS, its parent company) to listen, what books should boycotters target to get to the United Farmworkers’ 10 percent threshold? Probably the big ones like…the Bruce Springsteen memoir. Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer-winning novel, All the Light We Cannot See. Maybe Shonda Rhimes’s bestselling memoir, Stephen King’s latest? How about Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything — cited as one of the “Seven Books You Need to Understand (and Fight) the Age of Trump“?

Even if such a boycott was successful in harming the bottom line of a publisher, how do we know in a capitalist society that the publisher wouldn’t then make up the difference by publishing even worse things or being less inclined to take risks? S&S started Salaam Reads, a imprint for Muslim-themed children’s books. Why not starve “that person’s book” financially and publicity-wise, and instead buy two books from Salaam Reads?

Bookstore owners and buyers, who are the most direct link in all of this, are starting to formulate statements and implementing plans. Kathy Crowley, co-owner of Belmont Books, a Boston-area store set to open this spring, is a writer herself, and she told me that she and her husband have decided “Belmont Books won’t sell this book.” She adds, “Though I do want S&S to feel the heat for this decision, boycotting all S&S authors seems neither fair nor likely to be effective. More likely, the boycott generates lots of publicity for the book, raises the hackles of the anti-PC, pro-[‘that person’], pro-Trump crowd, and, in the end, rewards S&S and [‘that person’].”

On the other coast, Christin Evans, owner of The Booksmith, a 40-year-old institution, which is, she said “specifically located in the historic Haight Ashbury” section of San Francisco will skip over “that person’s” book (and anything from the Threshold Editions imprint), cut the number of S&S books, and, of the remainder, donate any profits from S&S books to the ACLU “for the foreseeable future.”

The extremity of what’s coming requires we actually lay out on the table what we stand for. If we stand for a free exchange of ideas, we have to support publishing. Can we instead reject this person’s ideas and collectively stop giving him a platform? If publishing is a business, can we vote with our dollars and our attention (cultural capital)? Store owners can decide whether to stock this title or not, reviewers can review or not. But a blanket boycott of any publisher’s books makes no sense. It’s burning down the house because you saw a spider.