1.

The Bolsheviks shot ’em, chopped ’em up, threw ’em in a hole, poured acid on ’em. This was my high-school History teacher’s recounting of the Romanov murders. He sat at the back of the classroom grading while we watched a video, the people of the early 20th century jerking along soundlessly in black and white. Then the finish: the forest of today, grown up where the scattered royal bodies had recently been found and DNA-tested, proving the story was all real. In spite of two of the skeletons being missing, this was passed off as a happy ending.

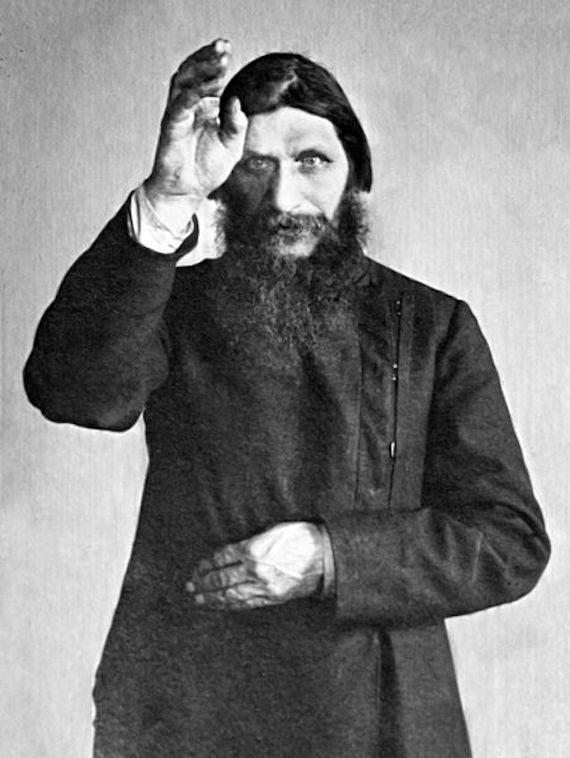

Grigori Rasputin came up too, of course, and took over. They couldn’t kill him. Poisoned him. Shot him. Clubbed him. Tied him up and threw him in the water. Intrigued by the whiff of the dark, I wrote a long, galloping essay about him. I stared at his stark photographs in books, sucking up descriptions. He smelled like a goat, and always had food in his beard, yet was extremely attractive to women. He looked that way. Like someone who stank and didn’t care, whose lack of caring was behind his ability to get any woman naked in a hurry. Under his caveman brow, his eyes were pale and startling. “A flaming glow,” as Boney M. put it in the song about him and the Russian queen. My parents had the album.

I could see how the eyes got to that queen (another Alix, as I noted with a thrill). I’m sure I included them in the essay. I got a B, and was irritated. I was usually an A student, a prim compiler of what teachers wanted to hear. “Great! A little inconclusive,” the teacher wrote in red. There was something I clearly hadn’t gotten at. Something I didn’t see, or didn’t yet know how to write about. And didn’t know was coming.

2.

This year, I didn’t see Donald Trump’s election win coming either. At home in British Columbia, watching poll results on my phone half the night, I drifted into bleary memories of high school, of sadistic boys, of History class. Rasputin floated up again when I skimmed an article about Trump seeking to bro down with Vladimir Putin. Trump is no Mad Monk, but there are other similarities. Like Rasputin, he projects himself as a “man of the people” with heroic powers, including the ability to transform a sick country into a healthy one. Like Trump, Rasputin was proud of his genitals, and enjoyed grabbing and kissing and firing others once he got some governmental clout. And both he and Trump show themselves as ringmasters of narrative: they tell their own heroic stories, and reroute everyone else’s.

That’s especially true of women’s stories. Aside from persuading the queen that he was cousin to Jesus Christ and knew everything she was thinking, Rasputin told “my little ladies” that sleeping with him wasn’t the sin they had been brought up to believe, but conversely, a sin-removing act. Trump is similarly possessive about “my women,” but is a less subtle deflector. We’ve all heard his “Pussygate” responses: the accusers are wrong, the assaults never happened, they’re liars. This technique spreads easily. When his campaign manager was accused of aggressively grabbing a female reporter by the arm, Trump said, “Perhaps she made the story up. I think that’s what happened.” It goes beyond gaslighting; it’s a rewrite, or a writing-over.

Like many people who’ve been sexually abused, I’ve gone over and over my past in my mind, keeping it mainly to myself. And like them, I’ve felt chewed up and spat out by this presidential victory and what it’s peeled away from the world. A lot of women I know have said the election result feels personal, and it has surely reanimated old occurrences for us, things we thought were dead. Inconclusive things. Things with zombie afterlives that are difficult to tell. Here’s one of them.

3.

All the things you don’t remember line themselves up first. After watching so much political posturing, I now feel the need to note that, to defend my honesty upfront.

I don’t remember leaving the party at the house near the river in Oxford, where all my A’s had taken me. I was studying English Literature there at the end of the 1990s. I don’t remember getting back to my college closer to town, going up the stairs to my room, putting the key in the lock, turning on the lamp inside. He must have been with me all the way. I feel the need to list details, too. There were three flights of stairs. He was in a tux, I was in a long gown. Oxford parties often required oddly formal dress, and we’d sit around on the floor drinking like that, as though we were minor Russian royals from some other time.

I look for connections, trying to give this story a shape.

I don’t remember what we talked about, walking over the cobbled street in the cool winter night. We must have talked. I do remember sitting on my small couch chatting about families. I liked talking about mine then, with anyone who would listen. And complaining about things wrong with England: the eyedropper pressure of the showers, the clerks’ pain upon eye contact at the grocery store. I was very obviously homesick. I’ve wondered since if that marked me.

He wasn’t Russian or American. He was English. I can’t remember his eye colour. He had glasses.

My room looked out onto the shoulder of the chapel next to the quad. It was late, it was dark, as we sat by the windows. I do remember being cheerfully drunk, amused. I don’t remember us getting into my narrow bed. I don’t remember how we started kissing. I do remember stopping and telling him, “I don’t want to have sex with you.” His odd compliments: You’re so feminine. You’re so female.

How I ended up out of my rustling pewter ballgown: No.

His weight: Yes.

The pain when he pushed into me: Yes.

I said nothing else, except asking him to finish, so it would stop. He did, and fell heavily asleep with his arm over me, blurting out Bloody fucking in his dreams, twice. I had wavery, still-drunk thoughts about pregnancy and disease. These seemed to be far away but coming, trains that had left their stations. I held very still.

I remember him leaving in the earliest morning with a kiss and his number, and me going along with it, already deciding this script would make things better, though I felt like a wasteland. Chopped up and thrown in a hole and covered in acid, yes. Him calling later to say, “I owe you an apology. I’m sorry I raped you.” His voice was slightly abashed in that English way, permanently level. And me trying to figure out what to reply.

No words came to mind. I still hadn’t slept. I was sitting at my desk, trying to work, with the heavy curtains closed against the white sky. I’d taken a shower, avoiding thinking about what I was washing away. I’d stripped the navy sheets from the bed and taken them straight downstairs to the laundry. He stayed on the phone a while, mentioned his girlfriend, how he had one, yeah, and he was sorry about that too. I’m not sure which seemed worse to me at that moment.

Then all I did was think, for weeks. All the old donkeys trotted out in the service of rape explanations. Your fault, your drunkenness, your strapless dress, your taking him to your room, your kissing him back, men can’t help themselves, men can’t stop themselves, nobody knocked you unconscious, it wasn’t your first time, you asked him to finish, you must have wanted him. And others, less clear. Your unanchored need. You wanted to talk with him, you wanted to meet someone, the cute story, the happy end. Isn’t that why you went to parties?

Via email, I blurted out a summarized version to a guy I knew, as if a male witness would cement it. His reaction: Are you sure? Rape-rape? I had nothing to say to that either. I think I wrote the rapist a blistering email at some point. But I’m not sure I sent it. My Oxford email address disappeared years ago, so I can’t check. Are you sure? That question never dies.

I tried to go on working, too, making a thesis out of piles of 19th-century research. In the Bodleian Library — everyone called it the Bod, which now made me queasy — I felt swallowed up. Waiting for my books to be delivered to my desk, I looked up at the faces of ancient greats painted high on the walls. Ovid was one. I remembered first reading his Metamorphoses as an undergrad back home in Canada. The people changed into rocks and trees and animals still felt human, still had human emotion, but nowhere to put it now. The back of my brain wondered: How was I changed? It was the same stew of disbelief and fascination I knew from reading fairy tales all my life, Russian or German or Irish, the ones that kept turning up in my research now. Girl into bird, sister into deer, queen into witch. How did it happen? What happened to her after that?

I tried to go on working, too, making a thesis out of piles of 19th-century research. In the Bodleian Library — everyone called it the Bod, which now made me queasy — I felt swallowed up. Waiting for my books to be delivered to my desk, I looked up at the faces of ancient greats painted high on the walls. Ovid was one. I remembered first reading his Metamorphoses as an undergrad back home in Canada. The people changed into rocks and trees and animals still felt human, still had human emotion, but nowhere to put it now. The back of my brain wondered: How was I changed? It was the same stew of disbelief and fascination I knew from reading fairy tales all my life, Russian or German or Irish, the ones that kept turning up in my research now. Girl into bird, sister into deer, queen into witch. How did it happen? What happened to her after that?

4.

The morning after Trump’s victory, I posted a broken heart on my Facebook feed. I usually hate emojis, but I was out of words, tired and blasted, as if it were again the morning after in Oxford. Another memory circled: the day, weeks later, when I was brusquely declared clear of pregnancy and sickness by the clinic, and went back to work in the library with a goodie bag of condoms they’d handed me. It felt like an ending, though it wasn’t, there isn’t one. Looking at that Facebook heart, I wanted to write my story, all of it, in point form or tweets or emojis, sure. Something shapeless.

Trump’s campaign brought the prevalence of sexual assault into the open, and then brushed it away. It felt like a nation turning its eyes on victims and asking what my male friend asked me: Are you sure? You’re not sure. Anyway, it doesn’t matter. There are other issues. Turn the page, tear it out, write it better.

He tells it like it is.

The subtext of that favorite comment of Trump supporters is this: That isn’t the story. He’s telling the story. Their impatience for the victory, the desired finish, is palpable. Trump has always wanted to keep hold of the narrative, saying, for instance, that he would be the one to “reveal all” about his accusers after the election. Rasputin did the same, teasing his followers along with opaque predictions about the future. After a financial fall in 1997, Trump declared, “Anyone who thinks my story is anywhere near over is sadly mistaken,” like Rasputin undying, staggering up from poison and bullets, controlling the tale until the absolute end.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons