When I was a student at the University of Delaware in the late 1990s, there were a handful of options for buying books in town. One was a midsized shop called Rainbow Books and Records, located amid the downtown’s Main Street bustle. I have few memories of actually buying anything there (though I did steal, for no good reason, a used Cypress Hill CD from the store; hopefully the crime’s statute of limitations has run out). There was a mediocre campus bookstore from which I bought a copy of Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland that I read eight or nine pages of. The best, by a wide margin, was the airy, endless Bookateria, where I spent afternoons searching for titles by Edward Abbey, Tom Robbins, Robert Pirsig, and whatever else might bolster my developing self-image as a chin-stroking bongside intellectual. Twenty years on, The Bookateria is still there — or so says the internet — and just thinking of it puts me there, my Birkenstocks (I was looking for Tom Robbins, remember) soft on its creaking hardwood floors.

When I was a student at the University of Delaware in the late 1990s, there were a handful of options for buying books in town. One was a midsized shop called Rainbow Books and Records, located amid the downtown’s Main Street bustle. I have few memories of actually buying anything there (though I did steal, for no good reason, a used Cypress Hill CD from the store; hopefully the crime’s statute of limitations has run out). There was a mediocre campus bookstore from which I bought a copy of Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland that I read eight or nine pages of. The best, by a wide margin, was the airy, endless Bookateria, where I spent afternoons searching for titles by Edward Abbey, Tom Robbins, Robert Pirsig, and whatever else might bolster my developing self-image as a chin-stroking bongside intellectual. Twenty years on, The Bookateria is still there — or so says the internet — and just thinking of it puts me there, my Birkenstocks (I was looking for Tom Robbins, remember) soft on its creaking hardwood floors.

There was also a fourth option, and I have no idea what it was called. In a wide alley off of Main Street, a miniscule bookstore existed for an equally miniscule length of time. Its lifespan, as I recall, was just a few months, but it might have been less than that. It was heavily curated, blue of carpet, and run by a prim white-haired woman with a courteous smile. Its metal shelves were home to midcentury cookbooks and color-plate nature guides, their prices written, almost apologetically, in the corners of their inside covers. The shop, so small and quiet — save for the waft of classical music — lent it the feeling of the quarters of a bibliophilic monk. Entering the store always reminded me that I was wearing dirty track pants and an old Phillies cap.

On one of my few trips there — I could feel the owner’s eyes, as if my CD-lifting reputation had preceded me — I came across a row of hardbacked, dark-blue novels. Their jackets were gone, and they stood together, naked, as if huddling against danger. Each spine bore the stamped name of the books’ author — Kurt Vonnegut— and, in smaller type, the title. I’d heard of Vonnegut, and vaguely knew that I should read him. I picked up Breakfast of Champions, read a few lines (“I think I am trying to make my head as empty as it was when I was born onto this damaged planet fifty years ago.” “I have no culture, no humane harmony in my brains. I can’t live without a culture anymore.”), and felt a surge in my chest. I paid the owner the lightly-penciled price of five dollars plus tax, waited for her pointlessly elaborate receipt, said thanks, and tore the fuck out of there. I had to read this book.

On one of my few trips there — I could feel the owner’s eyes, as if my CD-lifting reputation had preceded me — I came across a row of hardbacked, dark-blue novels. Their jackets were gone, and they stood together, naked, as if huddling against danger. Each spine bore the stamped name of the books’ author — Kurt Vonnegut— and, in smaller type, the title. I’d heard of Vonnegut, and vaguely knew that I should read him. I picked up Breakfast of Champions, read a few lines (“I think I am trying to make my head as empty as it was when I was born onto this damaged planet fifty years ago.” “I have no culture, no humane harmony in my brains. I can’t live without a culture anymore.”), and felt a surge in my chest. I paid the owner the lightly-penciled price of five dollars plus tax, waited for her pointlessly elaborate receipt, said thanks, and tore the fuck out of there. I had to read this book.

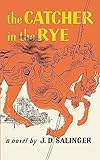

Breakfast of Champions felt, like a handful of other works — The Catcher in the Rye, of course, and later T.C. Boyle’s The Tortilla Curtain and the stories of George Saunders — wholly new to me, modes of communication that kicked through my mind’s thin walls. I’d never — and still have never — read anything like it. I suppose that any Vonnegut book would have had this effect, so distinctive is his style — that of a brilliant depressive, the vitality of his talent battling his downbeat vision — but Breakfast of Champions is Vonnegut’s loosest book, full of drawings and nonsense lines (“Dwayne Hoover had oodles of charm. I can have oodles of charm when I want to. A lot of people have oodles of charm.”) that gain menace as they mount. It seemed somehow right for this to be my first, the best route into his world.

Breakfast of Champions felt, like a handful of other works — The Catcher in the Rye, of course, and later T.C. Boyle’s The Tortilla Curtain and the stories of George Saunders — wholly new to me, modes of communication that kicked through my mind’s thin walls. I’d never — and still have never — read anything like it. I suppose that any Vonnegut book would have had this effect, so distinctive is his style — that of a brilliant depressive, the vitality of his talent battling his downbeat vision — but Breakfast of Champions is Vonnegut’s loosest book, full of drawings and nonsense lines (“Dwayne Hoover had oodles of charm. I can have oodles of charm when I want to. A lot of people have oodles of charm.”) that gain menace as they mount. It seemed somehow right for this to be my first, the best route into his world.

Breakfast of Champions isn’t my favorite Vonnegut novel, but it smacked me in the head with more force than any of his others — and possibly more than any other book I’ve read. I haven’t read it since that day in 1998, and I have only a dim memory of what it was about — something about a used-car salesman; something about cows. But that initial excitement has stuck; when I picked it up before writing this piece, something tightened in my throat. It was an artifact that had shoved me towards the person I would become.

And it seems somehow insane to me that I could have gotten it — this rousing, angry work that shook me by my spine — at that cramped and nameless store, overseen by a woman who, I’m guessing, had gone into business to occupy her time. Maybe her husband had recently died, and the quiet of her home had become unbearable — so she opened a shop that was just as quiet as the place she had escaped. Maybe she’d wanted to bring a touch of politesse to downtown Newark, Delaware, where music blasted from low riders and fistfights proliferated when the bars let out. Maybe she was engaging in a quiet fight of her own, selling pleasant books to the few students who might appreciate the gesture. Obviously — judging by its swift closure — there weren’t enough of us.

That I could have found a book that so enflamed me in such a serene, well-meaning place now seems to me a rude and minor marvel, like a tabernacle choir breaking into “Fuck tha Police.” The store has been gone for nearly 20 years, and its owner, I assume, has passed on as well. But they slipped me something important in the time we had together — and for that, I can only offer thanks.