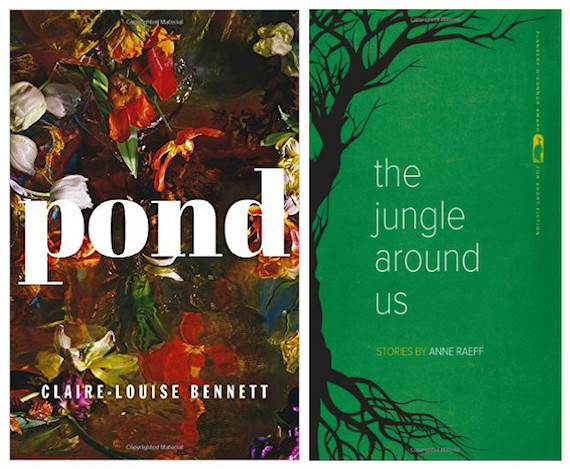

Sex, gender, and nature, a potent and sometimes winsome combination, aren’t a novelty in literature; they’re so inextricably entwined as to be almost obvious, fertile material for anyone probing at the edges of identity and environment. While D.H. Lawrence might have been treading new ground (pun intended) when his character masturbated onto the earth, while John Casey might have set his two lovers to tryst on the windswept seashore before they retired to a boat, it’s the women of contemporary fiction who are writing the latest revelations about interiority and exteriority, the tamed and the wild and the places where the two merge. The women in Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond and Anne Raeff’s The Jungle Around Us contain a wilderness that cannot be mapped.

What the wilderness outside possesses in mystery and density, so too do these characters’ inner lives contain veritable jungles, uniquely feminine experiences that rival the wiliest outdoor spaces in their mess, their beauty, and their inability to be wholly, completely known.

On their writerly surfaces, these books share few commonalities. Pond deals in freewheeling language that disorients and flummoxes, run-on sentences that fragment and dissolve in turn. Following the course of a single, unnamed narrator through her daily existence in the Irish countryside, in a ramshackle cottage whose quirks and malfunctions rend it almost a character, it zooms in close on the inner workings of a single, inimitable mind. In “Morning, 1908,” Bennett writes:

Everyone has seen a sunset — I will not attempt to describe the precise visual delineations of this one. Neither will I set down any of the things that scudded across my mind when the earth’s trajectory became so discernibly and disarmingly attested to. Peculiar things, yet intimately familiar. Impressions of something I have not perhaps experienced directly. Memories I arrived with. Memories that snuck in and tucked up and live on within and throughout me

The Jungle Around Us unspools more conventionally, with clean, digestible prose and stories that ambush the reader, stealthy in their impact. It follows numerous characters, primarily women (with a few men scattered throughout), and finds literal and metaphorical jungles in places as disparate as New York City and Mexico. The collection opens with “The Doctors’ Daughter,” wherein a 14-year-old named Pepa, whose family fled wartime Vienna for Bolivia, prepares to care for the homestead during her parents’ trip to the jungle on a medical mission. She describes the clinic attached to the back of the house as “painted a soothing blue like the eyes of an Alaskan husky, like winter.” After the doctors’ return, Pepa finds herself pregnant by a local boy named Guillermo, whom she would go to meet in the bordering forest. The ensuing abortion is as clinical as the story itself, haunting. Pepa sees “the instruments…lined up like soldiers, and everything smelled so clean.”

But beneath these superficial differences, the collections share an emphasis on the thorniness of femininity throughout time and space, whether present or past, in a city or a forest clearing. The unruly spaces in which these stories are set are a direct reflection of the characters’ inner lives, the turmoil and tranquility, the known and unknown. To be a woman is to arrive at a wilderness with a destination in mind but no map, the sprawling vagueness before you both a challenge and a threat. When there are so many ways to be, and so many pitfalls to encounter, women learn the topography by stumbling over it, step by step, the foibles as necessary and inevitable as the ascent.

Take, for instance, Raeff’s “The Boys of El Tambor,” in which Ester writes to her former lover, Amy, from the Mexican town to which she’s decamped after their breakup. “Nature” here is not so much canopies and blooms as it is dive bars and cheap hotels, a distinct, unfamiliar environment in which Ester can shed her past self and observe the world anew. Having given up painting and taken up a love affair with a straight couple, her experimentations in reshaping her identity are tethered directly to the permissive, occasionally debaucherous place in which she’s settled. Raeff’s descriptions of the central watering hole, El Tambor, take on the vibrancy and verve of a tropical space. She writes, “It’s completely pink. There’s not one wall, one chair or tabletop that is not bright pink. Even the napkins are pink, and the toilet paper, when there is toilet paper.” Ester loses herself in this cotton candy dream, swimming through memories and newfound sensations like one overtaken by a rip current.

In Pond, the natural landscape’s promises and disappointments mirror the narrator’s continual pogoing between expectation and reality, her thoughts that bounce like Ping-Pong balls from one subject to another, only to arrive at truths that demand a reckoning. In “The Gloves Are Off,” she fantasizes about the dreamy origins of the reeds that will soon thatch her roof, laid there by workmen who make lewd jokes and crane their necks for a glimpse at pretty girls. “I liked to think about all the little fishes that had nudged around and prodded at the reeds here and there…And the swans’ flotilla nests resplendent with marbled eggs,” she muses. Later, when she discovers that they’re sourced not from the nearby River Shannon but from faraway Turkey, the daydream abruptly shatters. As she’s pruning the garden afterward, her trepidation about the flora surrounding her cottage becomes apparent. “Oh, fuck the leaves and fuck the flowers!” she thinks. “I want to see naked trees and hear the earth gasp and settle into a warm and tender mass of radiant darkness.”

The writers’ respective views of nature differ. For Bennett, it is a constant presence, alternately a site of revelations and the menacing beast breathing at the back of the door. For Raeff, it’s background, the quiet symphony on the turntable that underpins the human drama at the fore. Yet despite their relative engagements with wild spaces, environment is essential for these characters’ trajectories. It’s a reminder that the woods and the psyche both startle us, be it with monkeys appearing in the trees in Raeff’s “Maximilano” or Bennett’s protagonist’s persistent daydreams of rape while passing a stranger on a morning walk in “Morning, 1908.”

In both collections, the marriage of environment and psyche, the overgrown thicket and the tangled brain, finds further footing in the characters’ caginess, their circumspect awareness of themselves or their reluctance to reveal certain facets to the reader. The cool, almost clinical tone of stories like “The Doctors’ Daughter” in The Jungle Around Us lends the collection an air of detachment, more impactful for its lack of sentimentality or melodrama. Still, it hints at further, unplumbed depths — there is no mention of how Pepa feels about her own abortion, only the stoicism she displays when faced with a trek through the jungle or a two-week stretch as the head of the household.

In Pond, the narrator’s breakneck narrative speed — her thoughts circling and derailing like a drunken carousel pony — means that certain revelations or milestones get treated with the same gravitas as replacing a malfunctioning oven (see: “Control Knobs”). It’s difficult to parse the significant from the mundane and easy to conflate the two, much like the barrage of stimuli one might encounter in a dense, wild space. The reader is subject to whiplash following the narrator’s trains of thought, the connections forged in unlikely and unconventional ways, and taking a psychological temperature proves difficult. When she nods to her character’s emotional state, Bennett tends to deal in koan-like non-sequiturs, spurs that jut from within the paragraph. After turning on a tap of water, the protagonist muses, “If we have lost the knack of living…it is a safe bet to presume we have forfeited the magic of dying.”

There’s a line in Bennett’s “Finishing Touch” that reads, “…I feel quite triumphant for having the good sense at last to realise that people who are hell-bent upon getting to the bottom of you are not the sort you want around.” For Bennett and Raeff, this might well be a manifesto. The women in these collections aren’t easily sussed. Their lives unfold in untamed spaces, jungles either literal or metaphorical, but their inner lives rival these environments, unknowable and wild.