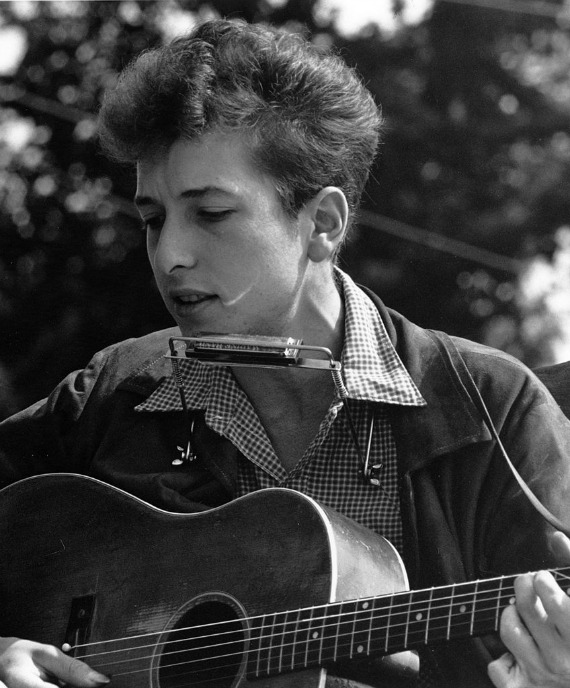

On the first page of his 2005 memoir Chronicles, Bob Dylan recounts his experience signing with Leeds Music Publishing company. It was 1961 and Dylan had just traveled to New York City from Duluth, Minnesota. He was twenty. He’d been written about once or twice in the music section of the Times, and that was enough to convince label executives that he was worth a deal. While walking around the office with Lou Levy, then the head of Leeds, Dylan bumped past Jack Dempsey, the famous boxer. Dempsey took a good look at him, sized him up, and said that he’d have to get a lot bigger if he wanted to be a fighter. Dylan politely told Dempsey that he wasn’t a boxer. He was a musician. A folk musician at that.

On the first page of his 2005 memoir Chronicles, Bob Dylan recounts his experience signing with Leeds Music Publishing company. It was 1961 and Dylan had just traveled to New York City from Duluth, Minnesota. He was twenty. He’d been written about once or twice in the music section of the Times, and that was enough to convince label executives that he was worth a deal. While walking around the office with Lou Levy, then the head of Leeds, Dylan bumped past Jack Dempsey, the famous boxer. Dempsey took a good look at him, sized him up, and said that he’d have to get a lot bigger if he wanted to be a fighter. Dylan politely told Dempsey that he wasn’t a boxer. He was a musician. A folk musician at that.

A few years later, at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, the now very popular Dylan played a routine acoustic set on Saturday evening. He played well-loved folk songs for an affectionate folk-loving crowd. But the next night, Dylan returned to the stage with a fully electric and amplified band — an apparent rock band. Despite persistent boos and jeers from the crowd, who shouted obscenities and felt betrayed by his newfound electric sound, Dylan played without batting an eye, and he sang “Like a Rolling Stone” with a special bite.

Before the Dylan Electric controversy and his signing with a major label, before Dylan even took up a guitar, there was Woody Guthrie, whose honest, traditional, and dedicated approach to songwriting inspired Dylan. Alongside “Song to Woody” and a few other early tries, Dylan wrote “Blowin’ in the Wind,” his first major hit. The song became largely identified as a protest song aligned with the civil rights movement; beyond its message, what arrested listeners was Dylan’s voice: it wasn’t cute or polished or even all that pleasant. It was a bit raspy, sometimes off-key, even wiry. He didn’t sound like someone who would be on the radio, and yet, there he was, standing in front of the nation, connecting with people on the basis of what he had to say, not how it sounded.

Bob Dylan has a built a career by defying expectations — as a kid who told Jack Dempsey he was a musician, as a folk performer trying to go electric, as a voice on the radio, and now as the first musician to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Dylan clearly infuses that same sense of defiance into his lyrics. The difference between listening his words in a song or reading them on a page is marginal. The power is always there, the inflection always inherent in his short, carefully rhymed (often internally rhymed) verses, his painstaking attention to rhyme and meaning existing on a continuum with hip-hop and slam poetry. Consider the long but wildly short-tempo “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” with its verse: “A question in your nerves is lit / Yet you know there is no answer fit / To satisfy, insure you not to quit / To keep it in your mind and not forget / That it is not he or she or them or it / That you belong to.”

If Woody Guthrie taught Dylan how to properly structure and perform a song, then the Bible gave him a wealth of phrases, ideas, and philosophies to put to poetic music. “Blowin’ in the Wind,” of course, is a reference to Ezekiel (12:1-2). Notice how Dylan changes the exact line — “The word of the Lord came to me: ‘Oh mortal, you dwell among the rebellious breed. They have eyes to see but see not; ears to hear, but hear not” — to a simpler, more poignant question: “Yes’n’ how many ears must one man have?” Dylan’s rephrasing of the line shapes it into its own rebuttal, a small but powerful twist of feeling that he’s mastered.

One of Dylan’s most critically acclaimed albums, Highway 61 Revisited, is rife with Biblical allusions. In “Tombstone Blues,” Delilah, a temptress from the Book of Judges, appears alongside John the Baptist. Cain and Abel are included in “Desolation Row,” while the title track “Highway 61 Revisited” opens with the moment when God asks Abraham to sacrifice a son. The whole concept of Highway 61, the road that stretches through much of the American heartland, rings with similarity to the Red Sea, the body that runs between the heart of North Africa and the Middle East and was significant in the story of Moses, one of Abraham’s descendants.

Taken together, Dylan’s intense interest in Biblical mythology seems to lean toward moments of conflict — a father being asked to kill a son, a temptress clashing with a saint, the feud between Cain and Abel. The Bible is filled with conflict, but these are intimate, personal conflicts of a different sort. Defiance arrives not with some sweeping turn of events or by divine intervention, but with the steeling of a person’s heart. Small victories that win big battles.

Conflict over death, sadness, and human faith were also the favorite themes of Dylan Thomas, the poet from whom Bob Dylan (born Robert Zimmerman) took his name. Thomas’s poems are often death-obsessed — the poet himself died young at 39. In “Clown in the Moon,” Thomas writes, “I think, that if I touched the earth, / It would crumble; / It is so sad and beautiful, / So tremulously like a dream.” The usual mood is there: reflective, honest, melancholy. In “Oxford Town,” Dylan maps this same mood over a song about racism in a small town. The last verse in Dylan’s song has an eerily similar feeling to Thomas’s: “Oxford Town in the afternoon / Everybody singing a sorrowful tune / Two men died ‘neath the Mississippi moon / Somebody better investigate soon.” The two poets meet somewhere in the middle — Oxford town in the afternoon, like a dream, haunted by sadness.

Thomas is also renowned for continually resisting the thought of death, best evidenced by poems like “Do Not Go Gentle (Into That Good Night)” and “And Death Shall Have No Dominion.” He writes, “Though they may be mad and dead as nails, / Heads of the characters hammer through daisies; / Break in the sun till the sun breaks down, / And death shall have no dominion.” This simple refusal to let grief and death take control of the beauty in his world was shared by Dylan, who again shaped the feeling into a powerful social outcry in “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.” “Take the rag away from your face,” Dylan sings hard-nosedly to mourners, “Now ain’t the time for your tears.”

If you take the lyrics of Woody Guthrie, the stories of the Old Testament, the poetry of Dylan Thomas, the styles of folk, rock, and blues, then it’ll add up to something like Bob Dylan’s literary style. His work is an ideally balanced marriage between content and form, like W. B. Yeats or Tennyson, with an air of social and political challenge.

The Nobel Prize cements Dylan’s legacy as a musician who shaped, in the words of the Swedish Academy, “new poetic expressions in within the great American song tradition.” He joins the ranks of other American laureates like T.S. Eliot, John Steinbeck, Toni Morrison. As someone who’s spent his life defying expectations, Dylan probably enjoys being in that company; like all great artists, he knows that he deserves to be there.

Image: Wikipedia