An “Any Soldier” care package was no curatorial feat. Rather, it was a cardboard box filled with good intention, a.k.a., Chef Boyardee and Dinty Moore cans, as had been skimmed from a pantry, or collected by a church drive. It seemed designed to make both recipient and provider feel precisely, lukewarmly O-K.

This was fine. It was lovely.

Still. No offense, but when a troop saw an open Any Soldier box, we generally moved on without a glance. We wagered that anything worth anything had been picked out or bartered, and we were just too spent for a letdown.

An unopened Any Soldier package, however, held value. Because no matter how hard you tried to murder hope — a mandate of the job — you couldn’t help but feel a flare of it ascend if you found an un-ravaged box. If you got to be the first and only Any Soldier.

This happened to me exactly once. The result: I learned about fiction from a box of Kurt Vonnegut books, Operation Desert Storm, 1991.

The scene was sand, and tent, and swelter, and blast concussion, and a small, unopened box, and me: a 19 year-old private in a camp in the desert void; a kid who’d gotten in enough trouble back home to risk his future, but who held enough privilege to get him out of said trouble; a kid whose father and grandfather had done tours in their respective wars. A white boy from the South who got into a state school based on base smarts and sub-base grades, the latter coupled to the asterisk* that he had joined the Army Reserve.

*He was a Good Kid who had found his way past setback c/o serving his country.

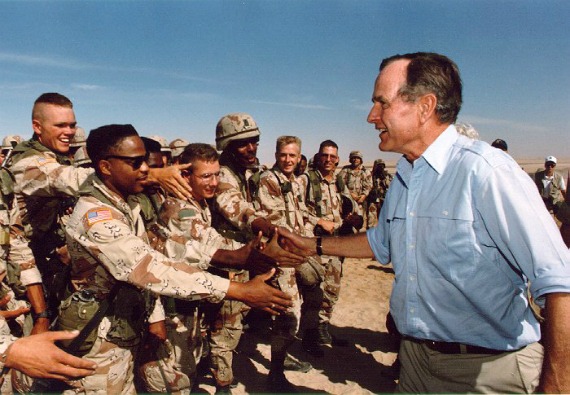

(At the time of my enlistment, the era of George H.W. Bush, the Army did not test for the chemicals I was fool enough to ingest.)

Point here was the Any Soldier box, unopened. No return address. I looked around as if to thwart a setup, then squatted on the sand floor of the tent and went at it. Ripping the tail of packing tape off of the top, I expected a reward of Spaghetti-O’s or Cheerios, or pray-God, Jolly Ranchers.

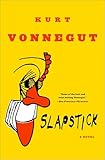

There was nothing there. Nothing but books. I read Slapstick out of obligation, and because it sat on top of the stack, and because its cover featured an illustrated clown. The titular allusion to clumsy, physical violence was wedded to the novel’s leitmotifs: “And so on” and “Hi ho.” Though employed as one-liner punchlines, these phrases also imported rhythmic, recurrent notes of social satire. “Hi ho” in particular addressed the futility of any given situation, including my own. It became a snare-pop to the ridiculous, We’re fucked, circumstance at camp, e.g., SCUD missile, Saddam, Sarin gas…Hi ho.

There was nothing there. Nothing but books. I read Slapstick out of obligation, and because it sat on top of the stack, and because its cover featured an illustrated clown. The titular allusion to clumsy, physical violence was wedded to the novel’s leitmotifs: “And so on” and “Hi ho.” Though employed as one-liner punchlines, these phrases also imported rhythmic, recurrent notes of social satire. “Hi ho” in particular addressed the futility of any given situation, including my own. It became a snare-pop to the ridiculous, We’re fucked, circumstance at camp, e.g., SCUD missile, Saddam, Sarin gas…Hi ho.

A few days later, when no one had rifled through the open box, I took it and stowed it in the sand under my cot. I then read Cat’s Cradle and Player Piano, before turning to the two texts I’d actually heard of, Slaughterhouse-Five and Breakfast of Champions. The former was a devastating, on-the-nose narrative about a veteran, Billy Pilgrim, whose life cycled back and forth through time, war to postwar, and again back to war.

A few days later, when no one had rifled through the open box, I took it and stowed it in the sand under my cot. I then read Cat’s Cradle and Player Piano, before turning to the two texts I’d actually heard of, Slaughterhouse-Five and Breakfast of Champions. The former was a devastating, on-the-nose narrative about a veteran, Billy Pilgrim, whose life cycled back and forth through time, war to postwar, and again back to war.

Yet it was Breakfast of Champions that snared me, that made me think about the writing process itself. Specifically, I fell in love with Vonnegut’s “picture of an asshole” on page two, a description wed to an illustration like an asterisk:

*

Alongside crude scrawl, I’d been unaware that one could build a narrative out of nonlinear snippets, or wield language as declarative and disruptive as “Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans’ Day is not.”

Christ, I thought, this is writing?

This was naïve. Breakfast had spent a year on best-seller lists before I turned three; there was a reason that even an applied non-reader like myself knew the name Vonnegut.

In fact, I realize now how puerile and/or unhip this reads. Whatever. Hi ho. Because in that desert, on the eve of the ground assault, as Warthog jets and tactical missiles slashed the sky, and as Republican Guard mobilized within striking distance of our compound, Breakfast’s complexity and humor, its polemic and timing and asterisk assholes were a revolution. Salvation, even.

Turns out the novel was the genesis text of “and so on,” having been published well before Slapstick. (I’d been reading the books in random order.) These three little syllables brought a gale force sandstorm. Importing both resignation and protest, and echoing the dehumanized, passive-aggressiveness of war, “and so on” represented everything my comrades and I were going through, and would go through.

Character-wise, I learned that Kilgore Trout could recur in additional works, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, Breakfast and elsewhere; that his biography could alter, as could his physical appearance; that Trout’s very presence may or may not have anything to do with the narrator in Slaughterhouse — let alone Vonnegut himself. In other words, a character did not have to look, act, feel, or even exist the same way, let alone stay in the same story, or in any story whatsoever.

Character-wise, I learned that Kilgore Trout could recur in additional works, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, Breakfast and elsewhere; that his biography could alter, as could his physical appearance; that Trout’s very presence may or may not have anything to do with the narrator in Slaughterhouse — let alone Vonnegut himself. In other words, a character did not have to look, act, feel, or even exist the same way, let alone stay in the same story, or in any story whatsoever.

The Rules, to employ Slapstick, had the consistency of a “sparrow fart.”

Thus, reading Vonnegut in the desert, I was introduced to character, language, setting, satire, narrative structure, leitmotif, and an asterisk asshole. I vowed to get home alive, and to write.

Though my life did inch toward letters, it took another Iraq War for me to go all in. This time, the scene was grad school, Chicago, in the post-9/11 world. I was 32. Alongside workshops and lit theory, I scoured the public library for the primer texts I had avoided in high school and college. I read “Hills Like White Elephants,” and wrote a weeper about a couple whose clipped dialog hovers just above their anguish. After reading Jay Mac et al., I produced a pair of astonishingly poor novels featuring bruised young men. I signed letters to friends back home with “so it goes” — the Slaughterhouse-Five catchphrase, as is repeated over 100 times in the novel — and did not cite my source.

I was working to be a writer, working quite hard, actually, but I was still mostly a mimic. Which was fitting, perhaps, since what came next was the most Billy Pilgrim-esque sort of echo: the call for a new war in the old desert — Iraq — against the old enemy — Saddam Hussein — as waged by a new President Bush. I was 19 again — only I wasn’t. I was a bystander to my own memory.

This time, instead of mobilizing for deployment, I marched in the streets, hurling slogans and pamphlets. One afternoon, I stood at the back of a massive protest that featured an African-American state senator as keynote. (He was the only politician brave enough to oppose the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and I loved him for that, and his wisdom helped him become President.)

Yet just like those Vonnegut stories, made absurd by their refrain, our efforts came to naught. The war launched anyway. I lost it; I lay on the floor of my tiny apartment for days, skipping school and work and meals and sleep, and watching the war on television. Hi ho. I also wrote, finally, furiously, my depression unspooling with every hour of embedded news coverage. A rerun, I concurrently watched and remembered the sand and soldiers, Saddam and Bush. I recalled the lessons learned as the Any Soldier who found Vonnegut, or, perhaps, who was found by him.

At some point, the news coverage flashed a photo of Shoshana Johnson, a young, African-American female soldier. Shot in the legs, she was one of the first troops captured by the Iraqis.

She went to war. I went on a search: through humor, pain, sarcasm, critique, polemic. Filth. Violence. Quirk. Only, I didn’t want to write about me. I wanted to write about soldiers whose war stories didn’t earn as much coverage (and/or our relationship to the coverage itself). What’s more, I needed to explore the culture of war, this Pilgrim-esque loop, this Vonnegut-esque recurrence, and how and why the hell we perpetuate it. I wanted to write my own version of an asterisk asshole. I wanted to pluck up the emotions of the faraway battlefield, and plop them right down in your kitchen, your office, your car wash. I wanted to bring the war home.

I sometimes regret that I have never sent those Vonnegut books to a new Any Soldier. Since 1992 I’ve only moved them from shelf to shelf, college to job, marriage to divorce, all over the country. Twice, they have spent a year in a pal’s garage while I traversed the planet. Slapstick and Slaughterhouse, talismans of sorts. My war story, my memory, as written by someone else — which is mostly the case with a war story, it seems. Billy Pilgrim cycles back, just as George Bush cycles back, as did my grandfather and my father and me. As did Shoshana Johnson, and the thousands of young troops on my television. Any Soldiers, all the time, locked inside a story.

Image: Wikipedia