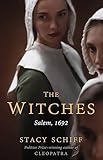

The Witches, Stacy Schiff’s novelistic examination of Salem in 1692, reveals how religious literalism and paranoia was baked into the New England soil. The first capital crime of the colonist’s legal code was idolatry. The second, Schiff notes, was witchcraft: “If any man or woman be a witch, that is, has or consults with a familiar spirit, they shall be put to death.”

Less than a year after Schiff’s book comes The Witch, the directorial debut of Robert Eggers. Labeled a “New England Folktale” and set in 1630, The Witch feels like an apocryphal precursor to the mania in Salem. The film begins with a town council banishing a Puritan family, likely based on the unidentified sins of William, the father. While the family soon appears happy enough on their own small, secluded farm, they are manacled by faith. The family does not simply believe in God; they fear the divine. Prayers are laments. God, impatient and unkind, is watching.

Less than a year after Schiff’s book comes The Witch, the directorial debut of Robert Eggers. Labeled a “New England Folktale” and set in 1630, The Witch feels like an apocryphal precursor to the mania in Salem. The film begins with a town council banishing a Puritan family, likely based on the unidentified sins of William, the father. While the family soon appears happy enough on their own small, secluded farm, they are manacled by faith. The family does not simply believe in God; they fear the divine. Prayers are laments. God, impatient and unkind, is watching.

William, it seems, has recreated God in his own image, imbued him with fire and vengeance, and not a small amount of interest in their farm and clan. We never learn much about the community from which the family has been cleaved, but we can assume that a literalist becomes even more literal when he reads sacred text alone. That said, William is more eager than evil. He casts judgments rather than aspersions. He truly loves his wife, Katherine, along with his children.

His young son, Caleb, is industrious, a good hunting companion. Twins named Mercy and Jonas are mischievous, and claim to communicate with one of the family’s goats, named Black Phillip. Mischief is a precursor to misery. Early in the film, Thomasin, the family’s teenage daughter, is playing peekaboo with the family’s newborn, Samuel. She closes her eyes, and the boy vanishes in a moment. A dark figure shadows through the forest with the baby, leading to a shocking scene of midnight ritual. Although it might be a product of its 17th-century setting, The Witch feels like a film that we should not see; events that belong on parchment, that are too legendary for moving images.

Anthony Lane sees the farm’s setting “on the verge of a forest” as the “classic habitation of a fairy tale.” He compares the film to the stories of the Brothers Grimm or the Venice-set Don’t Look Now. Both comparisons are merited, but there is a distinctly American tinge to The Witch, and it is not merely the fact that tales of baby-snatching witches were also a continental staple. Schiff writes that “As the magician molted into the witch, she also became predominately female, inherently more wicked and more susceptible to satanic overtures.” European witches flew; their displays of power were more vulgar. In contrast, “Continental witches had more fun. They walked on their hands. They made pregnancies last for three years. They rode hyenas to bacchanals deep in the forest. They stole babies and penises. The Massachusetts witch disordered the barn and the kitchen.” The devil works in mysterious ways.

Anthony Lane sees the farm’s setting “on the verge of a forest” as the “classic habitation of a fairy tale.” He compares the film to the stories of the Brothers Grimm or the Venice-set Don’t Look Now. Both comparisons are merited, but there is a distinctly American tinge to The Witch, and it is not merely the fact that tales of baby-snatching witches were also a continental staple. Schiff writes that “As the magician molted into the witch, she also became predominately female, inherently more wicked and more susceptible to satanic overtures.” European witches flew; their displays of power were more vulgar. In contrast, “Continental witches had more fun. They walked on their hands. They made pregnancies last for three years. They rode hyenas to bacchanals deep in the forest. They stole babies and penises. The Massachusetts witch disordered the barn and the kitchen.” The devil works in mysterious ways.

The devil in The Witch has his eyes on young Thomasin. In one scene after the newborn’s disappearance, Mercy and Jonas heckle their older sister near a river. Thomasin takes their bait and pantomimes as an actual witch, documenting the hellish actions she would take with children. The performance is too perfect: the twins know it, and the viewer knows it. Yet Eggers has more of a story to tell. The Witch is purely a New England tale, a descendent of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

After graduating from Bowdoin College in Maine, Nathaniel Hawthorne returned to his hometown of Salem. There he wrote “Young Goodman Brown” among other stories. A tale of a man discovering the “fiend” in his own “breast,” “Young Goodman Brown” reads as the product of Hawthorne’s own cloistered life.

In an 1837 letter to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Hawthorne wrote “By some witchcraft or other, for I really cannot assign any reasonable cause, I have been carried apart from the main current of life, and find it impossible to get back again.” Malcolm Cowley thought Hawthorne’s “self-imprisonment” in Salem was an essential time in his artistic life; those years were “his term of apprenticeship and his early travels, corresponding to the years that other American writers of his time spent traveling in Europe or making an overland expedition to Oregon or sailing round Cape Horn on a whaler…Left alone, he traveled into himself and worked or idled under his own supervision. It was the Salem years that deepened and individualized his talent.”

“Young Goodman Brown” demonstrates that talent. It is one of those tales anthologized into simplicity, a staple of American Literature high school reading lists. Yet the story remains clever and rather chilling. Brown sets off on a journey that “must needs be done ‘twixt now and sunrise.” His wife of three months, Faith, is worried. She has good reason to be; Brown is heading for the wilderness. The story never hides his “present evil purpose,” and that forms the first connection with The Witch. New England horror is less about surprise and more about the slow burn of suffering. In Hollywood, horror sneaks into your home, leaps from behind doors; in New England, horror festers in your soul.

Brown meets the devil in the forest. The path he has taken was lined with the “gloomiest trees,” which “closed immediately behind” his entry. The devil knows his grandfather and father; in fact, “I have a very general acquaintance here in New England. The deacons of many a church have drunk the communion wine with me; the selectmen of divers towns make me their chairman.” Of course, this is typical Salem fare: the devil is in each of us. Yet Hawthorne, like Leo Tolstoy, remains long enough in the moments of his stories to force us to look deeper. Brown continues alone into the forest, which becomes transformed. Trees creak, wild beats howl, and even the “wind tolled like a distant church bell.” It seemed as if “all Nature were laughing him to scorn. But he was himself the chief horror of the scene, and shrank not from its other horrors.”

That shift — “The fiend in his own shape is less hideous than when he rages in the breast of man” — weds Hawthorne to The Witch. If Thomasin is the potential vessel for evil, then her father opens the door for the devil. William’s lie about the disappearance of his wife’s silver wine cup becomes an act of betrayal. Whereas at the start of the film he might resemble, in stature and temperament, the father from Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, he might best be considered Goodman Brown. The burning light of God has blinded him to the evil in front of his face.

That shift — “The fiend in his own shape is less hideous than when he rages in the breast of man” — weds Hawthorne to The Witch. If Thomasin is the potential vessel for evil, then her father opens the door for the devil. William’s lie about the disappearance of his wife’s silver wine cup becomes an act of betrayal. Whereas at the start of the film he might resemble, in stature and temperament, the father from Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, he might best be considered Goodman Brown. The burning light of God has blinded him to the evil in front of his face.

As Hawthorne’s tale enters its final quarter, Brown becomes maniacal as the “benighted wilderness pealing in awful harmony together.” He discovers what resembles a witches’ Sabbath in the forest, lead by the devil. Brown and his wife are about to be the newest converts, ready to be baptized in sin. Yet in a move so common in such tales, Brown finds himself “amid calm night and solitude” in the tranquil forest, with no sign of the fiery ritual remaining.

Hawthorne’s extended description of the dark Sabbath shows that its reality was present in Brown’s soul — the only place that matters. In The Witch, characters carry the forest to their farm, their beds, their hearts, and then return to that darkness for more. Unlike Brown, what they experience is fully real, quite bloody, and surprisingly disturbing. The Witch is worth watching for a new approach to old horror: the feeling that we have heard this story before, and that is exactly why it scares us so much.