“Judge Irving Kaufman, of Rosenberg Spy Trial and Free-Press Rulings, Dies at 81.” The 1992 New York Times obituary stated that Judge Kaufman hoped “he would be remembered for his role not in the Rosenberg case…but as the judge whose order was the first to desegregate a public school in the North.” Kaufman was appointed to the federal bench in Manhattan in 1949. Two years later, the “espionage trial of the century” landed in his courtroom.

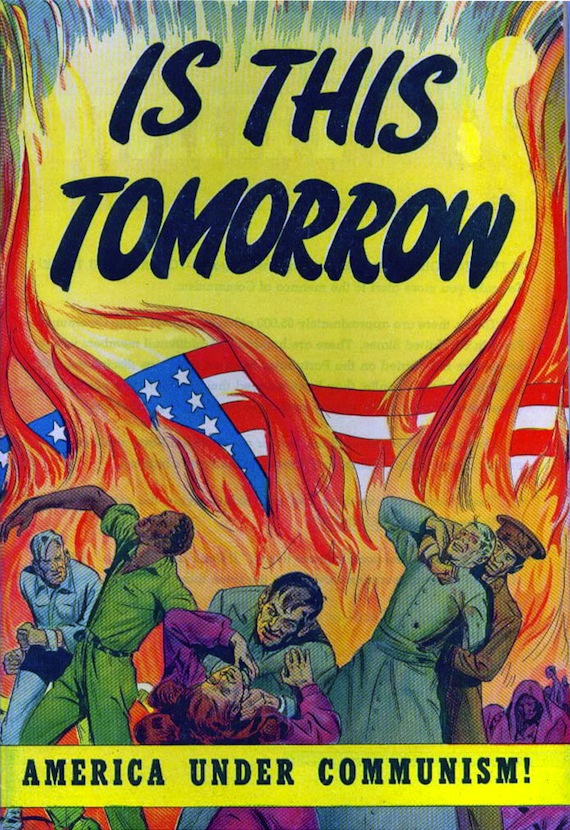

Consider the backdrop. America, flush with victory, was pivoting to Cold War politics. Redbaiting was in; Fireside Chats out. Against the shiny orange roofs of proliferating Howard Johnsons and the pulsating floors of teenage sock hops, the country was off to war again. This time on the Korean peninsula, fighting a new enemy called Communism.

Our literary imagination remains captive to this era, as if we could jump in a Studebaker and road trip past the nostalgic caricature of ourselves to discover something new. In her seminal The Future of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym opines: “Nostalgia is a sentiment of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy…The twentieth century began with a futuristic utopia and ended with nostalgia.” We may not be stuck mid-century, but if Mad Men is an indication, we’re still trying to figure a few things out.

Our literary imagination remains captive to this era, as if we could jump in a Studebaker and road trip past the nostalgic caricature of ourselves to discover something new. In her seminal The Future of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym opines: “Nostalgia is a sentiment of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy…The twentieth century began with a futuristic utopia and ended with nostalgia.” We may not be stuck mid-century, but if Mad Men is an indication, we’re still trying to figure a few things out.

“Damn Cold in February,” part of Joni Tevis’s stunning new essay collection, The World Is on Fire, combs the 1950s for atomic kitsch. Tevis lines up Buddy Holly with choice snippets of U.S. government operating manuals (and propaganda), artifacts to underscore the era’s cultural ironies. In 1957, The New York Times “explained how to plan one’s summer vacation around the ‘non-ancient but none the less honorable pastime of atomic-bomb watching.’” After winning Miss Atomic Bomb, “a local woman poses for photos with a cauliflower-shaped cloud pasted to the front of her bathing suit.” Tevis clicks through the slides of an atomic view-master toy and concludes, “Not only do Americans want to see the bomb, we want to become it, shaping our bodies to fit its form.”

It turns out, however, that it’s much less fun once the Russians have it. In 1949, a successful Soviet nuclear test threatened our self-image as supreme in the world, invoking terror around the country. Treason took on new meaning with rumors of espionage and leaks of classified documents to our former ally Russia. Everyone, it seemed, was building a fallout shelter — public buildings, apartment houses, families. School children practiced for bomb attacks.

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was all about the Russian threat. HUAC revved up in the late-’40s, holding hearings the broadcasts of which stoked public fear and paranoia. Congressman Richard Nixon cut his teeth crushing the distinguished public servant Alger Hiss, convicted of perjury — not espionage — charges the merits of which are still debated. Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy fulminated, wielding a list of alleged Reds lurking in the State Department. HUAC pitted neighbor against neighbor and colleague against colleague, destroying careers in Hollywood and plenty of others too. Old Blue Eyes may have been ascendant, but celebrated actor/singer Paul Robeson went down for his politics.

Enter Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. They bonded over the Communist Party the tenets of which, they believed, would level the playing field between the haves and have-nots. Julius, an electrical engineer, and Ethel, an aspiring actress/singer turned secretary, were struggling to provide for their two young sons on New York’s Lower East Side when the FBI set them in its crosshairs. The Rosenbergs were indicted in 1950 — Julius on atomic espionage charges for passing secrets to the Russians, and Ethel as his accomplice. Ethel was denounced on apparently false charges by her brother, David Greenglass, an Army machinist at the weapons installation in Los Alamos. To state the barest facts — the Rosenbergs were tried in 1951, found guilty of conspiracy to commit espionage, and given the electric chair on June 19, 1953.

Jillian Cantor steps into this space with her forthcoming novel, The Hours Count, narrated by Millie Stein, fictional neighbor to the Rosenbergs. Millie’s consuming interest is her son, David, who appears to be autistic. Largely estranged from her family, Millie is unable to connect to her husband, Ed, a surly and often drunk Russian, who may or may not be entangled in nefarious political activities.

Jillian Cantor steps into this space with her forthcoming novel, The Hours Count, narrated by Millie Stein, fictional neighbor to the Rosenbergs. Millie’s consuming interest is her son, David, who appears to be autistic. Largely estranged from her family, Millie is unable to connect to her husband, Ed, a surly and often drunk Russian, who may or may not be entangled in nefarious political activities.

This isn’t the first time Cantor has fictionalized history. In Margot, Cantor imagines Anne Frank’s older sister to have survived, living in Philadelphia. Like Margot, The Hours Count is narrated by a woman who declines to swim through history’s riptides, but instead bobs passively along. Perhaps the passivity of these narrators is meant to bring the surrounding characters into focus. In The Hours Count, Ethel Rosenberg is such a character, portrayed as a devoted wife and mother, and a caring friend.

Much of The Hours Count is taken up with Millie’s strange and conflicted relationship with a man who promises to help her disabled child. Dramatic scenes from the Rosenbergs’ execution at Sing Sing are spliced throughout the novel. But the main part of the story breaks off when Ethel departs for the grand jury, leaving her two young sons in Millie’s care.

Ethel never returned. She refused to testify against her husband and was taken straight to prison, leaving her boys behind. Michael and Robert Rosenberg were six and 10 when their parents were electrocuted three years later. They were ultimately adopted by Abel and Anne Meeropol, changing their last names to Meeropol. (Abel Meeropol, incidentally, wrote both the words and music to the iconic song, “Strange Fruit.”)

What of those children, purposefully orphaned by the State? E.L. Doctorow takes them on in The Book of Daniel, tackling the whole raging tragedy. Reimagining them as Daniel and Susan Isaacson, Doctorow explores the agonized years between their parents’ arrest and execution when they moved among harsh grandparents, private homes, and an orphanage. He gives us the lawyer who not only had the thankless task of representing their parents, but also worked tirelessly to find an appropriate home for Daniel and Susan. (The lawyer’s widow accuses the Isaacsons of causing her husband’s untimely death.) And the anguished stepparents, who cannot staunch Daniel’s fury, nor heal his sister, a former radical dying in a mental institution. “Today Susan is a starfish,” Daniel says. “There are few silences deeper than the silence of the starfish. There are not many degrees of life lower before there is no life.”

What of those children, purposefully orphaned by the State? E.L. Doctorow takes them on in The Book of Daniel, tackling the whole raging tragedy. Reimagining them as Daniel and Susan Isaacson, Doctorow explores the agonized years between their parents’ arrest and execution when they moved among harsh grandparents, private homes, and an orphanage. He gives us the lawyer who not only had the thankless task of representing their parents, but also worked tirelessly to find an appropriate home for Daniel and Susan. (The lawyer’s widow accuses the Isaacsons of causing her husband’s untimely death.) And the anguished stepparents, who cannot staunch Daniel’s fury, nor heal his sister, a former radical dying in a mental institution. “Today Susan is a starfish,” Daniel says. “There are few silences deeper than the silence of the starfish. There are not many degrees of life lower before there is no life.”

Published in 1971, The Book of Daniel remains as charged as a live wire. This big meaty book follows Daniel as he plunges into the radical 1960s, an angry young father on a quest to confront the people in his parents’ and thus his own drama. He suggests his parents mistook shared political ideology for friendship, and socialist doctrine for life advice. Of lessons learned from his father, who “ran up and down history like a pianist playing his scales,” Daniel says, “I heard about the framing of Tom Mooney and the execution of Joe Hill, and all the maimed and dead labor heroes of the early labor movement. The incredibly brutal fate of anyone who tried to help the worker.”

Cousin Linda, whose father betrayed Daniel’s mother and got 10 years instead of death, tells him, “neither you nor I was responsible for what happened. But we’ve borne the brunt…This is what happens to us, to the children of trials; our hearts run to cunning, our minds are sharp as claws.”

The real children, Michael and Robert Meeropol, have dedicated their lives to bringing justice to their executed parents. Their continued presence on the public stage subverts nostalgia; if you’re paying attention, it’s pretty tough to get sentimental about this time period. In August 2015, The New York Times ran a lengthy Op Ed by the Meeropols, pleading their mother’s case and urging her posthumous exoneration. Their father might have been “legally guilty of the conspiracy charge, but not atomic spying,” but their mother “was prosecuted primarily for refusing to turn on our father.”

“The government held her life hostage to coerce our father to talk, and when that failed, it extracted false statements to secure her wrongful execution…[with] disturbing implications in post-9/11 America.”

What about the judge who meted the sentence, Irving Kaufman? Doctorow portrays him as an ambitious man who saw the trial as a means to advance his career. Here’s Daniel’s father, describing the fictional Judge Kaufman. “Not having known of [the judge’s] existence even a few short months ago, [he] knows a good deal more about him now, including [the judge’s] most intimate professional secret, that he hopes to be appointed to the Supreme Court. All the lawyers in the corridor know this. [The judge] has heard more cases brought by the government in the field of subversive activities than anyone else.”

In 1960, Judge Kaufman published a lengthy piece in the Atlantic Monthly called “Sentencing: The Judge’s Problem,” in which he asserted his belief that judges should have wide discretion in sentencing. “In no other judicial function is the judge more alone,” Kaufman wrote. Judges take their role seriously; every judge “is painfully aware of what five years without a father may mean to a prisoner’s son.” Moreover, sentences that are too harsh “have historically had an effect opposite from the one intended.” A judge should have the “satisfaction” of saying “to oneself, ‘I have never consciously rendered an unjust decision.’”

It’s not a leap to read this article today as post hoc justification for sending the Rosenbergs to their deaths. Whatever its intent, the following year Kaufman received a promotion to the Second Circuit Federal Court of Appeals where he served more than a quarter century.

The trial and execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg are sobering reminders of how public sentiment can affect the wheels of justice. The Rosenbergs were tried within a particular context: Congress inflaming the Red Scare, the country again at war, and mounting fears about the A-bomb. Ideally a judge would take extra precaution to separate hysteria from legitimate danger. Judge Kaufman, it seems, thought he would do well to embrace the times — “The general attitude of the public toward a particular type of crime…must be taken into consideration if respect for the law is to be upheld.”

Perhaps we’d best let the Meeropols have the last word: “Neither of our parents deserved the death penalty.”

Image Credit: Wikipedia.