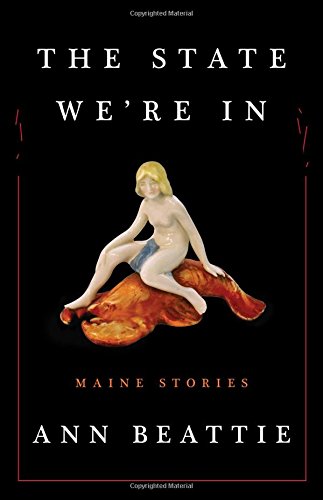

Ann Beattie has been writing short stories for more than 40 years. For some readers, she remains associated with the Baby Boomer generation and specifically the 1970s when she first started publishing. But her style and approach have changed over the years, and even if she’s not as associated with the zeitgeist as she once was, her output in the 21st century — which includes both new and selected volumes of short stories, novels, novellas — demonstrates that she has not slowed down, nor has she abandoned new ideas and approaches.

Beattie’s new book The State We’re In: Maine Stories is a collection of loosely linked short stories about people living in the state, some more permanently than others. We spoke back and forth over e-mail while she was on the road about linked short stories, Maine, and ending a story.

The Millions: Where did the idea for the book start?

Ann Beattie: I never have ideas. I don’t plan or plot. My husband was in Europe on vacation with his brother, and I decided to sit down and start writing and see what happened. The month before, I’d written [the short stories] “Road Movie” in rough draft, and “Missed Calls” in more-or-less final form, so maybe I was also slightly in a Maine state of mind…but if I remember correctly, when I wrote “The Fledgling,” I was just seeing what I could write in the first hour after I sat down. Then I remembered how much fun it can be to write.

TM: Why do you find Maine an interesting fictional space?

AB: I suppose I might feel so much an outsider, or simply so negative about a place that it wouldn’t be something I’d want to visit in fiction, but Maine is like any other place to me. I wasn’t at all trying to define anything about the state. Since I’ve lived here for about 25 years part of the year, of course some things were right there at my fingertips. Had I found the fledgling in the recycling bin in Virginia, I would have set the story there, I guess.

TM: There are a lot of people who will read this book who have never been to Maine and only know the state through Stephen King, Richard Russo, Carolyn Chute, and Murder, She Wrote. Were you thinking of this and playing with that knowledge or expectation?

AB: Yes, would be the short answer. I hear conversations all around me, I know both people who live here 12 months a year and tourists, and the state also gets tons of publicity, so I think I have many perspectives on how people think of Maine. While I do think vaguely of my audience when I write (though I hope it’s never a predictable audience; I really write for myself and a very few other people, initially), I write whatever I’m inclined to write, because a writer shouldn’t outguess or in any way condescend to her audience.

TM: What made this a story collection as opposed to a Robert Altman-esque novel with many central characters–or a Beattie-esque novel like Falling in Place, say?

TM: What made this a story collection as opposed to a Robert Altman-esque novel with many central characters–or a Beattie-esque novel like Falling in Place, say?

AB: Good question. But I’ve already written Falling in Place, so wouldn’t want to use that exact structure again. Also, at first the stories seemed more unrelated than they turned out to be. In many cases, I fought the impulse to have more cross-overs or walk-ons, or scenes in which this character meets that character (which would have been easy). I didn’t get to the character I think of as most central, Jocelyn, until I had about half the stories in what became the book. Then her story got longer and longer. If the whole thing had been a seesaw, Jocelyn would have easily tipped the balance and sent the other characters up into the air to dangle. That would have been counter-productive, so I didn’t restrain myself from writing so much about her in first-draft, but afterwards — inspired by my husband’s helpful thoughts (hi, honey!), I realized it might work well to divide the material and intersperse her ongoing story with other stories that were not inconclusive, but best understood in terms of their stand-alone connotations as separate stories. Is that clear enough? What I mean is, her story was too big to stand alone and not interrupt the book, but I hoped that the little stories orbiting her would work two ways: that hers would comment ultimately on them, and that they would add some perspective, etc. to hers.

TM: Why did you resist having characters appear in other stories. I ask because I suppose that’s an obvious option when writing stories set in the same place. Even in a book like this, do you want each story to stand completely on its own?

AB: One way to answer the question would be that the reason I resist writing related short stories has to do with my writing method, which is not to pre-plan a story. If I knew characters were hovering in the wings that should be incorporated, I’d worry that it would determine, too much, what story I wrote next. That doesn’t seem to me enough of an answer. I’m quite aware that things reappear in my stories, such as Patsy Cline songs. I deliberately take something — some object — and see if it looks different, or works differently, from story to story. Like everyone else, I also take the chair in the living room and see if I like it better in the bedroom. That doesn’t exactly answer the question, either. With the disclaimer that there are books of stories in which the characters reappear that I like very much, I tend to be moved by stories in which the writer begins and — I guess — in some sense concludes lives. It’s a little like watching someone dance under a strobe light. How you capture what it looks like is the initial difficulty (even sunlight is really no less of a problem), but if you represent the dancer, even if she’s moving through differently colored lights, or waving her arms more than before, then it’s the dance you’re watching, not the dancer. I suppose the argument could be made that that would be just fine. Or the joke: Ah, Beattie’s next collection will be linked stories. I doubt it.

TM: I know that you live there part time, but does Maine feel like home to you?

AB: No. The house in Maine feels more or less like home, but then I go out.

TM: Does that make it easier or harder to write about a place?

AB: I honestly don’t know. I think, in general, it helps me to feel comfortable enough in a place, but not too comfortable.

TM: Do you write and discard — or at least not publish — a lot of stories?

AB: I’d say 30 or 40 percent are discarded entirely.

TM: How long did The State We’re In/em> take to write and how does that compare to other collections?

AB: Not so long. It’s one summer’s stories, though that says nothing about how they were ordered or what time I took discarding individual stories and making revisions.

TM: How do your stories typically start? Did it change in any way for the stories in this collection?

AB: It did change with this book. I didn’t set out to write a book, just to see if I could write some rather short stories that I hoped would be on some level pretty direct (such as the ones that involve conversations, like “The Stroke” or “Silent Prayer”). It took me a while to realize how much almost all of them were stories about how people tell stories — whether epistolary (“Missed Calls”), or mostly gossip, or with people trying to write stories but living them instead (“Duff’s Done Enough”). If you look at the book as a collection of women’s voices — different women, telling stories — that would seem right to me. That strikes me as more of a common denominator than the state of Maine. As for the first part of the question — almost everything I write starts with a visual image, even if its position gets rearranged later.

TM: Do you write stories with an ending in mind?

AB: Never.

TM: So how do you know when you’ve reached the end of a story? Because so many of them don’t conclude per se.

AB: To me, using a different way of thinking (a different part of my brain, no doubt), I’ve begun to sense, as a story stretches out, where it is going and what small things are operative (motifs, etc.). I try to allow myself messy rough drafts, but that’s different from having good instincts and eventually guessing, as I write, where a story is headed (though the specifics surprise me all the time). How do I know when I’ve reached the end? When there’s a critical mass I could explain, but since any good story is never just a riddle to be solved, nothing would make me articulate that, except in the vaguest sense, to myself — functioning as writer first, but thereafter as reader.

TM: In your Paris Review interview you said that when you started writing, there wasn’t another short-story writer you wanted to emulate. Do you see writers now who have followed what you’ve been doing?

AB: No comment. But not unrelated: writers are in dialogue with other writers. Sometimes they’re mimics, rather than originators — right?