This post was produced in partnership with Bloom, a literary site that features authors whose first books were published when they were 40 or older.

1.

In his most recent book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, Malcolm Gladwell devotes a lengthy chapter to the proverbial fish-in-pond question: Is it better to be a big fish in a small pond, or a small fish in a big pond? Most of us would surely answer, “Well, it depends” — and Gladwell (with his characteristic passion for truisms) acknowledges as much:

In his most recent book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, Malcolm Gladwell devotes a lengthy chapter to the proverbial fish-in-pond question: Is it better to be a big fish in a small pond, or a small fish in a big pond? Most of us would surely answer, “Well, it depends” — and Gladwell (with his characteristic passion for truisms) acknowledges as much:

There are times and places where it is better to be a big fish in a little pond than a little fish in a big pond; where the apparent disadvantage of being an outsider in a marginal world turns out not to be a disadvantage at all.

Two of these times and places, according to Gladwell, are 1) Paris in 1874, and 2) Brown University in recent years. In the case of the former, he refers to the first independent exhibition mounted by Impressionist painters, who for years had failed to gain access to the prestigious Salon and accompanying patronage such access guaranteed. Their scenes of everyday life, indistinct figures, and visibly expressive brushstrokes did not at all please the tastemakers of the day. When then-outsiders Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet led the charge in April 1874 to hold their own small, DIY exhibition apart from the Salon — 30 artists in three rooms on Boulevard des Capucines, in contrast to the Salon’s massive production in which paintings were hung floor-to-ceiling on countless walls — it was a risky, scandalous moment. They were scorned by the Academy and its patrons. But their goal was to “advance without worrying about opinion,” and this they accomplished. It was, in Gladwell’s unqualified estimation, “better” that the Impressionists — at the time a mere collective of unknown, experimental painters — chose to be big fish in the little pond of their own making. History would, of course, agree.

Gladwell’s contemporary argument — which focuses on choosing a college and is exemplified by the story of a young woman named Caroline Sacks — can be summed up thus: when it comes to indicators of success, how smart or talented you are is not as important as how smart and talented you feel. Caroline Sacks earned her ivy-league degree, but, in the end, she didn’t pursue studies in science, which was what she loved; she was subsumed by competition and feelings of inadequacy. “If I’d gone to the University of Maryland, I’d still be doing science,” she says. Gladwell’s conclusion is that it’s better to place yourself in a milieu where you feel confident and visible rather than inferior and lost-in-the-crowd. In an intellectual environment, being a little fish in a big pond is demoralizing; demoralization leads not only to failure but eventually to quitting your path, sacrificing your dreams and passions to the deep-sea bottom of the big pond.

Notwithstanding Gladwell’s oft-maligned tendency to oversimplify — to make social science of anecdotes — his arguments at the least proffer hypotheses worth taking out for a spin (his New Yorker essay on late bloomers was one of Bloom‘s site-launch inspirations, after all). When I consider the fish-pond conundrum, I find myself shifting to a different nurture-and-thrive metaphor (Bloom-related, of course): any gardener knows that when putting plants or seeds in the ground, you must mind the distance in between — too close, and they’ll compete to their detriment for air, sun, moisture, and nutrients; too far and weeds will fill the space, guzzling up the nourishment and leading to sparse harvest. In other words, living things thrive under definite environmental circumstances — including relative position to fellow organisms.

So the question for a student, or an artist, or anyone seeking to achieve goals and dreams might be: Where can I best blossom — upward and outward, deeply rooted and nourished?

2.

The pond that Dave and Reba Williams swam in was, initially, that of Wall Street finance. Dave had been an art lover since his youth, though. In his mid-30s, he found himself struggling in his career after “a couple of unlucky or poor employment choices.” He was married, with two children, and he needed to focus and get settled. Nevertheless, one day in 1968, a colleague told Dave about a prints exhibition, where he’d found original etchings and lithographs for sale in a manageable price range, and Dave immediately went to investigate. That day he fell in love with prints, and by 1975, Dave had collected some 25 prints, but he’d also undergone a seismically destabilizing divorce that left him with debts, alimony payments, and private-school tuitions. On the other hand, he was getting married again, to financial analyst Reba White, who would become his lifelong partner in the soon-to-be-launched adventure of print collecting — an altogether new pond for both of them.

Dave’s memoir, Small Victories: One Couple’s Surprising Adventures Collecting American Prints, is the story of the Williams’s 30-year journey in dogged self-education and research, collecting, and curating. Published earlier this year by David Godine, Small Victories manages to both sweep informatively through the history of American printmaking and stir the reader to ask herself how she too might pursue her creative projects with the same rare combination of joy, sense of mission, intensity, shrewdness, and humility that the Williamses exemplified.

Dave’s memoir, Small Victories: One Couple’s Surprising Adventures Collecting American Prints, is the story of the Williams’s 30-year journey in dogged self-education and research, collecting, and curating. Published earlier this year by David Godine, Small Victories manages to both sweep informatively through the history of American printmaking and stir the reader to ask herself how she too might pursue her creative projects with the same rare combination of joy, sense of mission, intensity, shrewdness, and humility that the Williamses exemplified.

Embarking on their art collecting adventure as a later-life second act and with financial limitations that many collectors don’t have, the Williamses recognized at the outset that they needed to choose their proverbial pond wisely. In 1978, when Dave landed a good position with Alliance Capital, he also landed an office space with empty walls that both he and Reba immediately saw as their “gallery.” “Big prints seemed like the answer for the expansive space,” he writes, “so we gradually added contemporary works by living artists. But this didn’t seem to satisfy.” And why not?

Contemporary prints were expensive. Even worse, we were doing what most other collectors were doing in the late 1970s, seeking the big, colorful prints that living artists continued to make following the 1960s ‘print revival.’ Moving with the herd offended my investment sensibilities. Living artists and fresh-off-the-presses prints provided little opportunity to discover new fields or obtain new insights. What could we contribute?

It wasn’t that they didn’t have the same acquisitive impulse of many collectors: by Dave’s own admission, he was image-addicted — “A fever can be treated and cured, but the only relief — temporary, of course — from the desire to acquire, is to acquire.” But hand-in-hand with that impulse was an implicit set of values that he and Reba shared, and those values only deepened as they progressed: “What could we contribute?”

I read the question as not purely selfless, yet still powerful when understood as a basic human need to do something impactful — to prosper by way of munificence. The Williamses needed an open space in which to root and thrive, a pond in which to swim and not just tread water among the throng. What they did, in fact, was dig their very own pond.

Reba proposed that we use the Alliance walls to build a big, affordable American print collection emphasizing less-familiar artists from an earlier time, the first half of the twentieth century. We would seek the work of artists whose signatures were not household names, try to find great prints by lost or forgotten printmakers. Less money, more prints.

It’s notable — and inspiring to me — that the fundamental assumption behind the project was that there is a vast trove of extant art that has been lost or forgotten; that what has risen to the surface as “great” or popular at different moments in history is incomplete. Commercial trends, media hype, the whims of good and bad fortune, and occasional nepotism inevitably elbow out quiet or challenging gems of great beauty and value. We can cite many examples of posthumously recognized masterpieces. And so, if you have an opportunity — plus passion and resources — it is a worthy endeavor indeed to seek out and discover what has been regrettably passed over.

The simple truth — that not all good or great art is recognized — is easy to forget. We can too readily entrust tastemakers of the day — the Academie of 1874 France, A-list publishing houses and magazines, even the Twitter kings and queens — to point us to ideas, works, and forms that are worthwhile. Recently I was made aware of a new online literary publication called the James Franco Review, the mission of which reads:

• This project is about visibility of underrepresented artists and narratives. Not satire.

• We have a desire for diverse literature and are questioning literary journals and the publishing industry. What happens when work is considered blindly? What happens when editors are asked to question where their tastes came from?At the James Franco Review, we don’t know why some stories and poems get published while others don’t, or what it means for something to be right for a magazine.

We seek to publish works of prose and poetry as if we were all James Franco, as if our work was already worthy of an editor’s attention.

An artist competing for an open space of recognition — the attentive reception due one’s unique talents and contribution — can only hope that there are James Franco Reviews, and Dave and Reba Williamses, digging their thoughtfully conceived little ponds all the time.

3.

As their brainstorms became more serious, the Willliams’s pond became even smaller:

[W]e established rules: only prints made by American — United States-citizen — artists; only prints made in the twentieth century, with emphasis on the first half of the century; and only prints featuring images of America. And the prints would mostly be black ink on white paper, not color.

Why these choices? We learned from dealers that American prints were under-collected by institutions and individuals. We saw them as bargains, compared to Old Master and nineteenth-century European prints. They were mostly American scenes, and they were mainly black and white…Most important, there were many, many possibilities to choose from, and not much competing demand. We dove into our new project headfirst, evading the collector herd.

Again, the Williamses fashioned a strategy that was equal parts pragmatism, ambition, and aesthetic passion. They wanted an open space — enough sun, air, and healthy soil, if you will. Enough opportunity for learning and discovery apart from cutthroat hordes. Having started on their project later in life, perhaps they also felt some propulsion toward more — bargains, and a large supply with little demand. Having moved in affluent circles, perhaps they knew too well the intense herd mentality of status-seeking among peers.

Reba was the voracious student and researcher. So when print dealer David Tunick said, “Spend just a few hours researching any aspect of American prints, and you’ll become the expert on that topic,” an additional appeal presented itself — to develop a bona fide expertise in a field as yet unpillaged by art historians. Reba went back to school, earning her PhD in art history from CUNY Graduate Center; her dissertation topic was the history of the Weyhe Gallery, a New York gallery that, writes Dave, “early in the twentieth century, did more than any other to promote prints by American artists.” With the scope of their pond determined, with Reba’s talent for research, with Dave’s “addiction” in full force, and with a mission to bring attention to the undiscovered driving them, they went forth to build a remarkable and renowned American print collection.

4.

Small Victories is filled with examples of how setting a clear, modest path, away from the din, can lead to moments of great discovery and reward. Dave writes, for example, about how prints from the 1930s WPA era opened windows onto that historical moment: “Although the WPA administrators demanded an uplifting and optimistic tone in murals, the prints were censored very little, probably because prints are often considered a lesser art.” Lucienne Bloch, who had worked as an assistant to Diego Rivera, was commissioned to paint a mural of children in a playground that was located in an African American neighborhood of Detroit.

She told us that the WPA administrators wanted only white children in the mural, so that’s what she painted. But she also made a realistic lithograph of the same scene with black children, titled Negro Playground, Detroit.

The Williamses acquired and later exhibited this print. Other WPA artists whose prints became part of their collection included Joseph Vogel, John Langley Howard, Florence Kent Hunter, and Rockwell Kent.

Their WPA research led to other screenprints made prior to the 1960s pop-art explosion. Dave writes that they were “the first collectors to take early screenprints seriously and do the necessary research,” and thus, as David Tunick had earlier predicted, they became “the experts” and “changed perceptions about early screenprints, rescuing them from the art orphanage and reviving them as sought-after collectibles.” Screenprint artists that made up this part of their collection included Ralston Crawford, Harry Sternberg, Elizabeth Olds, Ernest Hopf, Anton Refregier, Hugo Gellert, and Ben Shahn.

In 1991, after an exhibition of their prints at the Newark Museum had proved disappointing because their curatorial partner had “wanted to show only the best-known prints by the best-known artists, while we wanted to show great work by lost and forgotten artists,” the Museum’s director, Sam Miller, asked the couple a question that sent them on their next mission: how many of their prints were made by African-American artists? Miller was interested in mounting that exhibition.

Once they determined that only one print in their collection qualified — Sargent Johnson’s “Singing Saints” — the Williamses set out to locate and acquire more; if the work of African-American printmakers was under-collected and under-exhibited, they wanted to change that (as did Sam Miller). “We took an unorthodox approach — and one we never used again. We sent Reba’s list [of more than 50 African-American artists] to every art dealer we knew, or had even heard of, and offered to buy any prints made in the 1930s and 1940s by any of the artists on Reba’s list for whatever price the dealer asked.” They succeeded in buying up more than 100 prints. With such an aggressive approach, they did face trust issues. When the African-American artist Raymond Steth heard about their buying binge, he came in person from Philadelphia with his portfolio to make sure they were worthy buyers; he made them promise to never sell his prints and to donate them to a major museum.

What likely earned Steth’s trust was Dave and Reba’s evident love for the work they collected. Dave writes in detail about every artist and print featured in Small Victories, demonstrating his intimate relationship with each print and passing that involvement on to the reader. Of Steth’s print “Heaven on a Mule,” Dave writes:

It is a remarkable print, an emotional experience…Steth explained that there was a religious cult that believed that if you put on wings, went to a hilltop with all your earthly possessions, and prayed, angels would come and take you to heaven. In the print, a commotion in the clouds overhead hints that the angels are on their way.

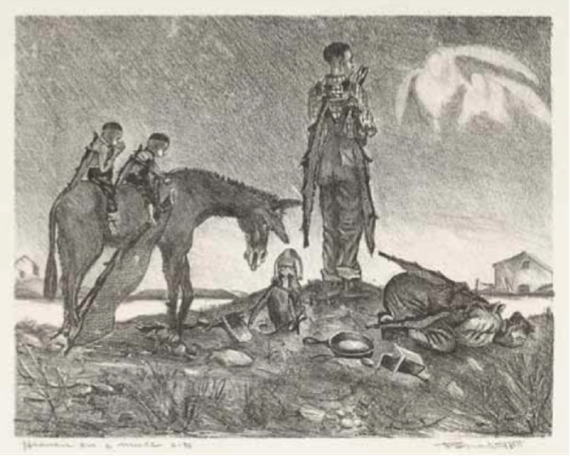

Of a depression-era print, Raphael Soyer’s “The Mission,” Dave writes:

The scene is in a church mission, and the hollow-cheeked, near-starvation poor are concentrating on their coffee and bread — except for one. A central figure stares out at the viewer in anger, eyes intense and mouth tightly drawn. I can read his mind: “I’m mad at the world. It’s not my fault, but I’m desperate and can’t do anything about it.”

Along the way, many delightful discoveries were born of their decision to stay focused and small: prints from short-lived, forgotten creative movements like Indian Space; the discovery that Connecticut, where they had settled by 2007, had been home to a major American Impressionist colony (which they only learned when they agreed to a small exhibition at the Greenwich Historical Society); a beautiful collection of flower prints all done in black-and-white that innovated modes for capturing the essence of “color” via monochrome aquatints; and little-known experimental works by star artists who, when making prints, were free to depart from their best-known styles, e.g. Frida Kahlo’s only print, “Frida and the Miscarriage,” and Alex Katz’s atypically black-and-white “The Swimmer.”

5.

I write all of this from Paris — 140 years after that first Impressionist exhibit, and yet I’ve decamped here this summer for the very reason of finding a bit of open space. I have lately come to realize that fierce competition — whether the hothouse of literary commerce, or the more general ubiquity of unbridled American capitalism — dampens me: I need a regular antidote, lest demoralization set in. Throughout my life I have, by no conscious choice of mine, swum in big ponds, and as a small fish have not fared particularly well. The older I get, the more I seek open spaces and warm souls. I want to grow, upward and outward, deeply rooted and nourished.

But what of the value of competition and intense selectivity? In a Slate article, ”The Trouble With Malcolm Gladwell,” psychology professor Christopher Chabris writes:

Perhaps tough competition gives students a more realistic view of their own strengths and weaknesses. An accurate sense of one’s own ability could help the process of acquiring expertise….Finding your skills may trump following your passion.

If you can’t cut it, maybe it wasn’t meant to be; you have to compete to find out. Competition separates the contenders from the dabblers.

Well, it depends. Of course I come back to what it means to be a “Bloomer,” embarking “late” on a venture or passion. When you’ve lived a little, you perhaps better understand that in the school lunchroom of life, the cool kids’ table is an illusion; everyone’s eyes are wandering, and the competition to get seats at the one table is a sham. Also, Dave and Reba Williams likely did not wring their hands too much over their parameters: they hadn’t the luxury of time to waste, to fall in with the trendy multitude on roads well-traveled and wade toward some dribble of fulfillment. If they were going to make something of their mission, and enjoy it, they really had to start out thinking small.

Paradoxically, the imperative of efficiency spawns surprising and significant revelations — the fact that many talented fish have gotten lost or drowned in the big ponds of history, for example; and that a world in which institutionalized tastemakers are never challenged is a world lacking sorely in creative victories, small and otherwise.

Images courtesy of Dave H. Williams/David R. Godine.

Homepage image: Raphael Soyer, “The Mission,” 1933.