“Frank, we gotta take that clock.”

It was May of 1989, and Tony Rihner had just finished his drink, looked across the table at his old friend Frank Tripoli, convinced this was the night the heist would go down. Frank didn’t know it yet, but these older, slightly inebriated Butch and Sundance were about to go to Downtown New Orleans and take the clock off the front of the D.H. Holmes Department Store on Canal Street.

“Frank, you know they’re just gonna throw that clock away. They don’t understand what it means!”

To outsiders, the clock looked like nothing special, just a faded timepiece one might find at a Ninth Ward garage sale or in the bargain bin at a Royal Street gallery. But for over a century, the spot under the D.H. Holmes clock had been a famous meeting place for locals. Whether heading out to lunch or gathering after Saturday shopping, friends, parents, lovers, husbands, or wives would say, “I’ll meet ‘ya under the clock” and any New Orleanian would understand.

It was even a literary landmark. The Pulitzer Prize-winning novel A Confederacy of Dunces (Tony’s favorite book) opens with Ignatius J. Reilly “studying the crowd of people for signs of bad taste in dress” under the D.H. Holmes clock.

It was even a literary landmark. The Pulitzer Prize-winning novel A Confederacy of Dunces (Tony’s favorite book) opens with Ignatius J. Reilly “studying the crowd of people for signs of bad taste in dress” under the D.H. Holmes clock.

But things were changing. Dillard’s, a Dallas-based company had just purchased D.H. Holmes, at one-time the grandest department store in the South. Sadly, it fell to the same fate as the other New Orleans shopping landmarks that lined Canal Street: Godchaux’s, Maison Blanche, LaBiche’s, S.H. Kress all shuttered their doors one by one. It was the same story over the entire nation: Elegant downtown districts abandoned for the blander air-conditioned malls and parking lots of the suburbs. The wide sidewalks of Canal Street, once brimming with men in three-piece seersucker suits and women in Sunday dresses and white gloves, were now eerily empty.

But in the stillness, the octagonal face of the old D.H. Holmes clock still glowed, a relic of a disappearing New Orleans. Tony suspected it wouldn’t be there for long.

A few days before meeting with Frank, Tony went snooping around the old downtown store. One of his first jobs was approving credit on the fourth floor in the 1960s, a time when the storefront sparkled with lights and shoppers stopped in their tracks to marvel at the displays. But now looking through the dusty windows, he saw Dillard’s workmen in white caps taking down memorabilia — the portrait of Daniel Holmes, photos of the company baseball team and images of those smiling ladies who served up sweet macaroons and chicory coffee on the first floor café — all of them thrown in the trash. In true Ignatius-like fashion, Tony decided this ignominious fate would not befall the famous clock. Something had to be done.

Neither Tony nor Frank were sentimental. But they were what New Orleans blue bloods and Yankee writers would refer to as “Yats,” native-born and raised in blue-collar families. They carried with them an overwhelming sense of civic pride along with a distinct downtown accent that sounded more like Jersey City than the Deep South; often, their colorful vernacular was spicier than a cup of Galatoire’s gumbo. To Yats, the neighborhood, with all of its traditions, customs, and characters, must be protected, because they knew they lived in a place under perpetual threat of being destroyed, whether from a hurricane, oil companies, or corrupt politicians. It’s the small traditions — from eating red beans and rice on Monday to meeting under a clock outside a department store — that remind them that some part of this sinking city will endure. Those reminders are sacred, even if they seem trivial to the rest of the world.

“Frank,” Tony stiffened with determination, “we gotta take that clock.”

Frank hated what was happening to the city just as much as Tony, but they were 40-year-old married men and Tony’s plan sounded like a fraternity stunt. “Tony,” Frank answered, “you wanna steal something off the front of a building…on Canal Street?”

“Hey, we ain’t thieves,” Tony corrected. “We’re preservationists.”

Though standing a few inches taller than Tony, Frank knew protesting was futile. Besides, this couldn’t be any more dangerous than the time Tony roped Frank into running with the bulls in Spain. Chugging down his last sip of beer through his bushy mustache, Frank agreed to the plan. They would “preserve” the clock. “But first,” Frank said, “we need disguises.”

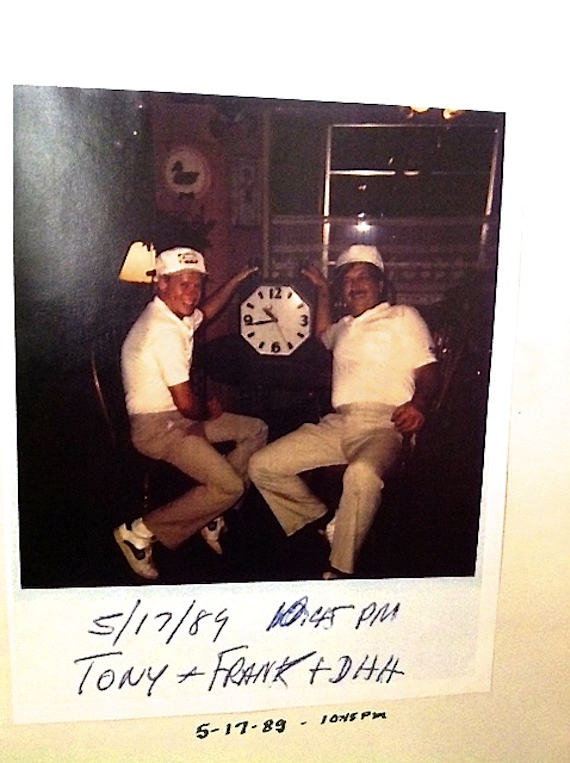

Attempting to look the part of workmen, they dressed in light khakis, white polo t-shirts, white sneakers and white caps. They grabbed a ladder and a few tools from the garage, piled into Tony’s Buick Riviera and drove to 821 Canal Street. It was a Wednesday night around 10pm. They could hear the ruckus from the bars in the French Quarter as they set to work loosening the bolts that had been in the overhead for more than 50 years. Occasionally, a curious pedestrian strolled by.

“Aw, my lawd” one lady said, “They takin’ down the clock!”

“Yes Ma’m” Frank replied.

Another passerby just stood there shaking her head in disbelief. For nearly 20 minutes Frank stood on top of the shaky six-foot ladder battling the long rusted bolts, while Tony kept watch. Exhausted, Frank handed the wrench to Tony who took his turn with the clock.

Then, by chance, or divine providence as she believed, Sally Reeves, the daughter-in-law of the President and Chairman of D.H. Holmes happened to come strolling around the corner. “Hey!” she yelled. “What are you guys doing?”

“We’re taking down the clock Ma’am,” said Frank

“And who gave you the authority?”

“Mr. Dillard” Tony said.

“I don’t believe you. My husband’s father was the president of D.H. Holmes. Give me your IDs.”

The jig was up. Frank, whose cool demeanor and towering presence always seemed to calm people, stepped closer to Reeves and explained their plan. She faced a decision. She could either let the two amateur “preservationists” take the clock or it would belong to a Dallas real estate tycoon. The question was, which was the lesser sin? “Well, I still want to see some I.D.” She wrote down their names and continued on her way.

Relieved, and somewhat vindicated by Reeves’s decision, the two set to work again. After 45 minutes, the last bolt budged and the 23-pound clock dangled from a thick electrical wire. Frank handed Tony a pair of uninsulated shears. As Tony clamped down on the wire, electricity surged through his body almost jolting him off the ladder. The clock dropped into Frank’s arms. It was exactly 10:45.

For a second, the two could hardly believe they had done it. They rushed the clock into the trunk, threw their tools into the backseat, and took off down the street. Racing down St. Charles, under the canopy of live oaks, the old friends laughed and hollered. It was time for a drink. They pulled into the next bar they saw and raised a glass to their success. That’s when Tony decided they needed to send a message. “Frank, call The Times-Picayune!” The Picayune was the local newspaper and while not exactly a Brink’s Job, the missing clock was still a worthwhile news item.

“What should we say?” Frank asked.

“Let them know someone saved the D.H. Holmes clock” Tony said. They were, after all, heroes, a righteous if not dynamic duo in the cloak of night protecting the hallowed icons of their city.

Frank nervously dialed The Picayune. When he was connected to the city news desk he blurted out, “The clock has been kidnapped!” then hung up the phone.

It wasn’t quite the message Tony had in mind, but they continued on with a victory celebration drawing the attention of two girls at the bar. “What are you guys so happy about?” they asked. Frank and Tony smiled, proudly walked the girls out to the parking lot, and opened the trunk to show off their prize. “Holy shit,” one of the girls said, “you guys are going to jail!” Unready to face such a sobering prospect, Frank and Tony quickly closed the trunk and decided to take the celebration back to Frank’s house. There, they posed with the clock for some Polaroid pictures: bringing it through the door, pointing to the time it stopped, and lounging on the couch with it. Then they packed it up and hid it in Tony’s house.

Officially, no one knew who had the clock, but Frank and Tony told the story to their friends. On special occasions, like a backyard 4th of July barbecue or a private Mardi Gras party, they would take it out to wow the guests.

“Mr. Dillard is gonna sue you guys!” their friends would say. But Frank and Tony didn’t care. “Let him sue us. I’ll steal the fucking thing again!” Tony retorted. And his friends would erupt in laughter and cheers.

For seven years they kept the clock. Then one day they got a call from a developer named Pres Kabacoff. Dillard’s had donated the old D.H. Holmes Canal Street store to the city of New Orleans and Kabacoff, a developer and preservationist of sorts, was turning it into a hotel. Sally Reeves provided him with Tony and Frank’s information in hopes that the clock could be restored to the building. At first the guys were suspicious. “Well, even if I did have it, what would you do with it?” Tony asked. Kabacoff explained his intention to restore it to its former glory. The guys explained they didn’t want any money. All they wanted was for people to meet under that clock, just like they used to do.

A few weeks later they got an invitation to the grand opening of “The Clock Bar” at the new Chateau Sonesta Hotel. Kabacoff explained it was a temporary placement, while they finished up renovations. But Tony wasn’t buying it. He could have held on to it until the renovations were completed. The clock wasn’t meant to be a wall ornament.

Eventually, Kabacoff made good on his promise. He moved the clock back to its original place, where it hangs today. In 1997 the city of New Orleans commemorated the literary significance of the site by installing a bronze statue of Ignatius Reilly underneath the clock. But sadly, few people wander by. The hotel constructed its main opening on the opposite side of the building, facing the French Quarter. The Canal Street entrance is the back door, which they keep locked. Other than the occasional devotee to John Kennedy Toole’s novel coming to pose with Ignatius, no one meets under the clock anymore. “It just isn’t what it used to be like in the old days,” Tony laments. “This was a vibrant meeting place. And now bums piss in that corner, just behind the statue.”

But Tony has no regrets. “That clock always belonged to us, the people of the city. As long as I’m alive, it always will.”

Special thanks to filmmaker David DuBos, who contributed to this article. DuBos is currently adapting Butterfly in the Typewriter into a feature film.

Photo Courtesy of Tony Rihner.