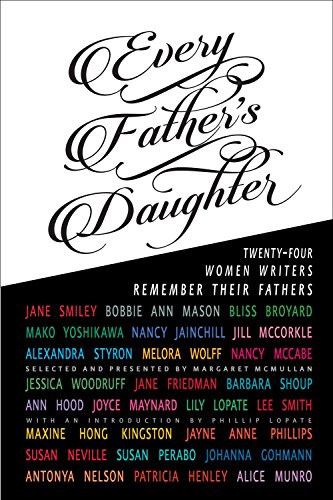

Renowned editor of The Art of the Personal Essay, Phillip Lopate is the director of the nonfiction MFA program at Columbia University. He and his daughter Lily, on break from Bryn Mawr, sat together at their home in Brooklyn, N.Y., to talk about their recent collaboration. Their Indiana friend Margaret McMullan joined them via Internet by providing emailed questions. Margaret and Phillip curated Every Father’s Daughter, a collection of 24 personal essays by women writers writing about their fathers. Phillip wrote the introduction and Lily, 20, wrote an essay about her father for the book. We present an abridged version of the conversation here, as a meditation on fathers, daughters, and family, ahead of Father’s Day.

Margaret: What is your ethical stance in regard to writing about family members or friends?

Margaret: What is your ethical stance in regard to writing about family members or friends?

Lily: Family is such a rich source of material — it’s hard not to write about. So I do. The writing is enjoyable; it’s like dishing about all of these inconvenient traits and recessive genes you’ve somehow acquired. It’s the act of publishing that’s tough. Unlike you, Dad, I’m filled with more trepidation. I weigh my rolodex…Who would I like to retain as a loved one? Who am I willing to discard and risk burning as an enemy?

Then again, my mother once threatened my father with divorce if he wrote about us. My father has, and two decades later my parents are still happily married. So the line of ethics seems open to interpretation.

Writing about friends is more taxing. In the process of writing, I often encounter problematic aspects about that person, which leads me to wonder to what degree we’re compatible. How far can our admiration for each other stretch? With family you’re able to perceive your subjects of study from a self-reflexive angle, but with friends, if you project yourself onto the page too much — it borders on narcissistic.

Phillip: For any writer of autobiographical nonfiction, it’s inevitable that you will bring in family and friends at some point. I try to gauge how much damage it will do to the person’s status in the world, not necessarily to their ego or sense of pride. I try to take their point of view into consideration, and not to write to settle scores. But I don’t always get it right, and I have given offense.

Margaret: Do you always write to be published? If not, what happens to those writings that were not meant for publication? Do you edit them?

Lily: It’s a process of natural selection to determine which pieces are publishing-worthy. A Darwinian critic might say a confessional essay is ready to be released but I think there’s something to be said for veiled intimacy. For now, the unpublished pieces are like secrets to myself.

I think my father wants to cleanse himself of all his secrets. He used to joke at the dinner table about having all his notes and manuscripts preserved in a library — as if it was an obligation my mom and I were expected to carry out. It depends on the library and the commission we would get.

Phillip: Except for my diaries, which I keep quite irregularly, I write everything at this point to be published. I used to write things just for myself, for fun or for the drawer, as it were, but now that my work is solicited, I do write with publication constantly in mind. Over the years I’ve developed a sense of my hypothetical audience’s response, which I’ve internalized. Sometimes I placate them, sometimes I try to provoke them.

Margaret: Phillip, did you ever imagine or fantasize that your daughter would be a writer? Did it happen naturally, or was it something you tried to make come about?

Phillip: That’s a good question. Since I teach young people who want to be writers, I know that it’s not something you can make come about; it’s up to the individual to persist. Writing is a hard life, and I don’t think I would have wished it on my own daughter, unless she showed strong tendencies in that direction. I suppose on some level I may have unconsciously willed it to happen, because it gave us something we could share and both be passionate about — a common language.

Margaret: Is there competition between the two of you? If so, does it ever grow out of a place of collaboration?

Lily: Is this a trick question? Absolutely.

The competition is definitely one of one-upmanship. I have a certain number of his genes running through my veins so that fills me with potential, but there is also an urgency to differentiate my white blood cells from his, so to speak.

When I started writing movie reviews in school newspapers, he showed me reviews he had written. He was harvesting a dialogue of comparison.

They advise couples that it’s tough to have a house with two writers. I think there’s truth to that.

I think we collaborate in that we both identify with writing as a survival tactic. Sometimes I’m resentful he’s passed this strategy on to me. But it’s a source of reassurance, being able to ask him a technical question when I’m away at college or commiserate over a book we’ve both read.

Growing up, when I’d work on five-paragraph essays, he was eager to help me break the strict rules my teachers had taught me. I think our competition has stemmed from admiration. I admire his ability to condense prose, so it’s encouraged me to be more ruthless in manipulating words.

Phillip: Yes, I would say so, on both counts. Lily is always eager to show me that she knows and understands more than I allegedly give her credit for. One time, when she was about 11 or 12, she put her hands around my head and said: “Daddy, you have a lot of knowledge inside there, but I’m going to be much smarter than you are, just you wait.” I said: “Go for it.” Sometimes, when she has asked me to help her edit a piece she’s written, she gets very testy and we have arguments over the proper way to express something. Then we settle down and proceed amicably through the piece. There have been times when she was writing an article for the school newspaper or a paper for a class, when I simply sat next to her and said nothing, and she wrote the whole piece from beginning to end without stopping. She has my sense of focus and determination. I also think she took comfort from my silent presence, just sitting beside her and reading a book while she worked. Writing is a lonely business, and it helps to have someone in the vicinity who has been through it. Those are some of my happiest memories.

Margaret: Lily, you grew up exposed to writers, poetry readings, book parties, and so on. What effect has that had on you as a budding writer?

Lily: Book parties and readings are affairs onto themselves. It’s definitely made me aware of the performance of writing and the “act” of being a writer.

At many of these events the writer is on display. One of my earliest memories is of my dad on the podium. In my four-year-old mind he looked so tall. So grand. It was like he was receiving an Academy Award. I still get an adrenalin rush when I see him read today.

I’ve been to writers’ events where there are other powers at play. The woman in the room who is encroaching with too much lipstick for an autograph, the agent watching the clock, the crowd that ranges from riveted to bemused. I always watch the writers who duck away from the crowd to steal a sip of water or wine — if their foreheads are sweating but they look alive with energy — that’s the exposure I really relate to.

Margaret: Phillip, did you already know you wanted to be a writer in college?

Phillip: I wanted to be a writer, but didn’t think I was smart enough. So I entered college pre-law. Then I looked around at the other wannabe writers who were my classmates, and they didn’t seem like geniuses either, so I figured what the heck, I’d give it a shot.

Margaret: How are your essays different from each other’s?

Lily: I think they’re very different. I tend to write with more dialogue or address an event from a side-long point of view.

He writes head-on and is filled with more narrative voice. His endings tend to be more brisk and staccato. As a reader, I really value endings so I linger in that section more. Perhaps I’m more of a nostalgic.

Phillip: The prevailing household lore is that Lily’s essays are very different from mine. My wife is quick to assert that they are, partly to support Lily’s own opinion that she writes in her own individual manner. She certainly has developed her own voice on the page. But frankly, I don’t think there’s such a big difference. I think our personal essays especially have a lot in common: we both use irony, self-mockery, humor, and bursts of candor for effect. It’s not at all because she’s imitating me, but rather, because we both share certain personality traits: a sardonic slant, a humorous realism bordering on pessimism, and a delight in entertaining the opposite of conventional, make-nice thoughts.

Margaret: What sort of character do you make yourself into in your personal essays?

Lily: A changeable one — who’s permitted to change her mind. In some essays, I’m observing a scene from the outside so my character is more contemplative and skeptical. In others, I’m immersed in the moment and exchanging dialogue — often filled with curiosity, pessimism, and longing. Regardless, she’s a character who doesn’t want to miss “the party” so she exposes herself to as many arenas as possible.

Phillip: I’ve played up the grump or curmudgeon side of myself, only to put it away at times. Overall, the character Phillip Lopate is someone who has an urge to be honest, almost an urgency, and a willingness to confess uncertainty or ignorance.

Margaret: What kinds of writing are you drawn to? Who are the writers who influenced you?

Lily: Raymond Chandler, Nora Ephron, Lena Dunham, Edmund Spenser, Nietzsche, Kafka, Plato, Natalia Ginzburg, C.P. Cavafy, Pablo Neruda, Jenny Han, Louise Glück.

Phillip: I fell in love with the great ironists: Dostoevsky’s Underground Man, Diderot in Rameau’s Nephew or Jacques the Fatalist, Nietzsche, Montaigne, Italo Svevo, Machado de Assis, Hazlitt, Lamb, Max Beerbohm, Sei Shōnagon. Also certain prophets of sadness, like Cesare Pavese, Walter Benjamin, Cavafy, Leopardi. But I also love Balzac, Whitman, Emerson — the large-hearted, maximalist writers.

Phillip: I fell in love with the great ironists: Dostoevsky’s Underground Man, Diderot in Rameau’s Nephew or Jacques the Fatalist, Nietzsche, Montaigne, Italo Svevo, Machado de Assis, Hazlitt, Lamb, Max Beerbohm, Sei Shōnagon. Also certain prophets of sadness, like Cesare Pavese, Walter Benjamin, Cavafy, Leopardi. But I also love Balzac, Whitman, Emerson — the large-hearted, maximalist writers.

Margaret: Lily, what do you think of your father’s writing?

Lily: What a loaded question. It’s like asking what I think of my father.

I’m a fan. I’ve always admired his critical reviews the most. Pieces he’s written for Harpers or The New York Times. He’s very good at distilling the main point for his readers.

When I read his personal essays, I feel like I’m chatting with him on the page. It’s similar to a conversation in person: funny, wry, and slightly unnerving.

Margaret: Phillip, what do you think of your daughter’s writing?

Phillip: I think she’s very sharp. You can feel a really searching intelligence at work in any piece she writes; there are always places with such sophisticated insight and perception that they take my breath away. Her prose style and argumentation are pretty strongly developed. For a 20-year-old, she’s way ahead of the game.