This post was produced in partnership with Bloom, a literary site that features authors whose first books were published when they were 40 or older.

1.

Lusty adj: Fired/Inspired by Pure Lust: Wanton, Gynergetic, Biophilic, joyous, merry, robust, flourishing, strong, powerful, vigorous, having an unrestrained inclination for enjoyment — Websters’ First New Intergalactic Wickedary of the English Language

“What does Shakespeare really have to say to women?”

I still remember the day Mary Daly stood in front of our class and asked that question. It caused a distant rumble in my head, like a deep tremor portending an earthquake. I spent the rest of the class, the rest of the semester, the rest of my life, trying to answer it. And with every attempt at an answer the fault line slid a little, the supposedly solid ground of my assumptions cracked and broke and fell away.

“What does any of this really have to say to women?” It’s a question I have been asking and trying to answer ever since.

That I was in Daly’s class at all was something of an accident. That semester I had kissed my first girl. We had been wandering around a local golf course one fall night, talking about anything and everything, when she finally reached across that indefinable space between us and pulled me to her. I was utterly smitten. I would have followed her anywhere. If she had been into race cars I’d have become a NASCAR fan. But she was a feminist — a radical feminist — and had been reading Mary Daly. So instead I went with her to womyn-only music festivals, hung out at lesbian bars, and since I was a student at Boston College, where Mary Daly taught, enrolled in her class. It took a little convincing, since I was in the Russian and Middle Eastern Studies department and Feminist Ethics wasn’t on my course list. I remember planting myself in Daly’s office to persuade her to let me in the course — the one she only allowed women to take — with all the clueless confidence of a good student who assumes that if it is written in a book, it can be learned. I had this idea that my new romance would be over before it got off the ground if I didn’t get into that class, so I wasn’t taking no for an answer.

That was my introduction to feminism. Not the slow or even sudden epiphany of the inherent misogyny of patriarchal culture, but a simple case of horniness and an overwhelming desire to impress a girl. I’m amazed that Daly took me on. But she was always a generous woman under the formidable rigor of her intellect.

2.

Elemental adj: [“characterized by stark simplicity, naturalness, or unrestrained or undisciplined vigor or force . . . CRUDE, PRIMITIVE, FUNDAMENTAL, BASIC, EARTHY” — Webster’s Third International Dictionary of the English Language]: This definition has been awarded Websters’ Intergalactic Seal of Approval

Daly was born in 1928 in what she called “the Catholic ghetto” of Schenectady, N.Y. She was possessed of a voracious intellect, something her parents and teachers recognized and, to their credit, encouraged, until she declared that she wanted to be a philosopher — not an acceptable profession for a young Catholic woman. Daly insists she didn’t know where this sudden determination for a life of the mind came from — “the school library had no books on the subject,” she wrote.

Daly was accepted into a small Catholic college, The College of Saint Rose in Albany, N.Y. Since they didn’t offer a major in philosophy, she studied English, presumably the next best option. She earned her masters at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., also in English, since her scholarship required she continue her course of study. But she approached her classes as a philosopher. Hers seems to have always been a study of the elemental nature of existence, of what later she would come to call “Be-ing.”

3.

Earthquake Phenomenon 1: the experience of cosmic shakiness, trembling, and dislocation, during which time Gyn/Ecologists share with our sister the Earth the agony of phallocratic attacks 2: Ordeal experienced by Crones engaged in the Otherworld Journey beyond patriarchy, which involved confronting one’s Aloneness as the ground splits open, and Spanning the chasm by Acts of Surviving, Spinning, and weaving Cosmic Connections — ibid.

Her determination to pursue studies in philosophy and Catholic theology eventually landed Daly at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. In the 1950s, Catholic universities in the United States did not allow women to study for the highest degree in the field — a Doctorate of Sacred Theology — and Daly would settle for nothing less. In Switzerland the faculty was state-controlled, and therefore it was illegal to exclude women. “None of the male students would sit next to me,” she would later recall. “They feared the temptations that might arise from sitting next to a female.”

She found the lectures stifling, but the intellectual demands bracing, and the connections she made with students exhilarating. She called it “seven years’ ecstatic experience interspersed with brief periods of gloom…a sort of lengthy spiritual-intellectual chess game.” Yet even in that rarefied ivory tower, the winds of change were stirring. Daly felt the breeze in 1965, when she visited Rome at the closing of the Second Vatican Council.

It’s difficult to overestimate the impact that Vatican II had on people of the Catholic faith. The Council was convened with the specific intention to understand the role of the Church and what it meant to be Catholic in a modern era. Daly remembers it this way:

The Rome of Vatican II was a sea of international communication — the place/time where the Catholic church came bursting into open confrontation with the 20th century. It seemed to everyone…that the greatest breakthrough of nearly two thousand years was happening. We met — theologians, students, journalists, lobbyists for every imaginable cause — and found our most secret thoughts about “the church” were not solitary aberrations. They were shared, spoken out loud, allowed credibility. There was an ebullient sense of hope.

That “ebullient sense of hope” came with a concurrent feeling of outrage when Daly attended a session at St. Peter’s:

I saw in the distance a multitude of cardinals and bishops — old men in crimson dresses. In another section of the basilica were the “auditors:” a group which included a few Catholic women, mostly nuns in long black dresses with heads veiled. The contrast between the arrogant bearing and colorful attire of the “princes of the church” and the humble, self-deprecating manner and somber clothing of the very few women was appalling. Watching the veiled nuns shuffle to the altar rail to receive Holy Communion from the hands of a priest was like observing a string of lowly ants at some bizarre picnic.

Daly returned to Fribourg inflamed with reformatory zeal, and wrote her dissertation on the role and place of women in the church and in Catholic doctrine. A few years later, having accepted a teaching position at Jesuit-run Boston College, she turned the dissertation into her first major book, The Church and the Second Sex. It was published in 1968 to wide acclaim. In 1969, Boston College fired her.

Daly returned to Fribourg inflamed with reformatory zeal, and wrote her dissertation on the role and place of women in the church and in Catholic doctrine. A few years later, having accepted a teaching position at Jesuit-run Boston College, she turned the dissertation into her first major book, The Church and the Second Sex. It was published in 1968 to wide acclaim. In 1969, Boston College fired her.

4.

Courage to Sin [sin derived fr. Indo-European root es- to be—American Heritage Dictionary]: the Courage to commit Original Acts of participation in Be-ing; the Courage to be Elemental through and beyond the horrors of the Obscene Society; the Courage to be intellectual in the most direct and daring way, claiming and trusting the deep correspondence between the structures/processes of one’s own mind and the structures/processes of reality; the Courage to trust and Act on one’s own deepest intuitions — ibid.

The Mary Daly I knew came into existence here, on the cusp of the second wave of the feminist movement. The Church and the Second Sex was a call to reinterpret Catholic doctrine from a feminist perspective — to see the equality of women as central to the message of love that the Church claims to preach. It was in many ways a response to that vivid scene in St. Peter’s.

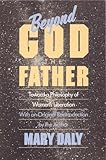

Her termination caused a series of protests among the then all-male student body. It was, after all, the late ’60s, even on a Jesuit campus. The college administration bowed to the pressure and not only rehired Daly, but gave her tenure. She would spend the next 30 years there, fighting different versions of that same battle for the right of women to speak freely. But by the time her tenure was granted she was no longer interested in trying to reconcile her feminist perspective with Catholic doctrine. Her next book, Beyond God the Father, rejects all organized religion. “A woman’s asking for equality in the church,” she once wrote, “would be comparable to a black person’s demanding equality in the Klu Klux Klan.” The Mary Daly I knew was no longer interested in giving those women in St. Peter’s a chance to speak alongside their be-robed and be-ribboned male colleagues. She told us that story when we were discussing Virginia Woolf:

Her termination caused a series of protests among the then all-male student body. It was, after all, the late ’60s, even on a Jesuit campus. The college administration bowed to the pressure and not only rehired Daly, but gave her tenure. She would spend the next 30 years there, fighting different versions of that same battle for the right of women to speak freely. But by the time her tenure was granted she was no longer interested in trying to reconcile her feminist perspective with Catholic doctrine. Her next book, Beyond God the Father, rejects all organized religion. “A woman’s asking for equality in the church,” she once wrote, “would be comparable to a black person’s demanding equality in the Klu Klux Klan.” The Mary Daly I knew was no longer interested in giving those women in St. Peter’s a chance to speak alongside their be-robed and be-ribboned male colleagues. She told us that story when we were discussing Virginia Woolf:

Let us never cease from thinking — what is this “civilization” in which we find ourselves? What are these ceremonies and why should we take part in them? What are these professions and why should we make money out of them? Where in short is it leading us, the procession of the sons of educated men?

I still have my copy of Three Guineas from that class, and it still falls open to that passage, underlined heavily in black ink. In fact, I have all my books from Daly’s classes. Some of the margin notes are embarrassingly naïve, but years later I still find truth in the passages I so earnestly marked, underlined, starred, and (as in the case of the above quote) copied out and taped to my dorm room mirror.

5.

Be-ing (verb): 1. Ultimate/Intimate Reality, the constantly Unfolding Verb of Verbs which is intransitive, having no object that limits its dynamism. 2. The Final Cause, the Good who is Self-communicating, who is the Verb from whom, in whom and with whom all true movements move —ibid.

From the early ’70s on, Daly’s theory of feminist ethics transformed into something more like a feminist cosmology. Finding no words in the English language to properly convey the free female existence as she conceived it, she created her own. Not as a secret society only available to the initiate (think of J.R.R. Tolkien with his interminable Elvish, or any Trekkie who claims to speak Klingon), but as a conquering of language, patriarchal overtones sloughed off, so that women could speak without constraint. Daly’s lexicon is a joyfully eccentric combination of puns, etymological emphases, and quixotic capitalizations:

boredom: a feeling of ennui

Boredom: the official/officious state produced by bores (that is, a synonym for patriarchy).

Her invented words with their reclaimed meanings first appear in Pure Lust. Eventually she had to write her own dictionary, which she called a wickedary.

Her invented words with their reclaimed meanings first appear in Pure Lust. Eventually she had to write her own dictionary, which she called a wickedary.

For a young woman coming to terms with her attraction to other women, that first class gave me a way to talk about women, and about what it was to be a woman, that felt true. That I didn’t know how to do this was not something I realized until Daly flat-out asked me: “What does Shakespeare really have to say to women?”

I hadn’t realized that was a question I could ask. Or needed to be asked. Mary Daly was by far one of the smartest and most intellectually brave people I’ve ever met. In all time I knew her, I never once heard her dismiss a student’s challenge, or reward someone for parroting back what she might want to hear. She liked a good argument, Mary Daly did. More than anything else she showed me how a person could be true to herself, a true radical, and still remain alive and awake to the world.

Taking Daly’s classes did not, by the way, keep my first female romance alive. Alas, the girl eventually left me for an ex-nun-turned-baker at a vegetarian restaurant. Who can compete with fresh baked bread? But I did eventually answer the Shakespeare question to my own satisfaction. I was far too fond of the plays to reject them in a fit of politically correct pique, and decided he did have something to say to women — to me, at least. Women speak in Shakespeare not on the grand stage of historic events that determine the fates of kings and countries, but in intimate exchanges; parrying words with the men who would be their lovers, husbands, conquerors, and companions.

And here they often eclipse the men at their sides. Shakespeare may not have written “feminist” women, but not one of them was a doormat. “Thou and I,” says Benedict to Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing, “are too wise to woo peaceably.” Women in the Elizabethan era were supposed to be docile and obedient. Shakespeare, I think, appreciated a woman with witty tongue and steadfast heart.

Daly’s exuberant feminist ethics have remained a steady guide in my life — a way to navigate, and interrogate, a culture that is often rancorous and toxic to its members. What does any of this have to say to women? As a lifelong student of Daly’s, I keep asking.

Homepage image by Mary Werner via The Feminist Art Project, Kansas Chapter