At the end of May 2015, during the first stirrings of the summer, I drove out to Bromley with my son, Dylan, in search of something to read. For some five miles, the road runs through the grey monotony of London’s southernmost suburbs, past stone-clad, semi-detached family homes, beneath drooping silver elms planted kerbside generations ago, past The Crooked Billet, now a Harvester family restaurant, once the site of wartime disaster. The large structure stands in a car park that is never more than half-full of hatchbacks, and, on a sandwich board perched half-on and half-off the path leading up the front door, the all-you-can-eat salad buffet is celebrated in garish lettering. On November 19th, 1944, the original Crooked Billet pub was destroyed when a V2 rocket struck. 27 drinkers died. I imagine them as elderly men in drab colours, leaning against the bar, knocking spent tobacco from their pipes, finishing off the dregs of Kentish pints, blinking obliviously as the silver rocket explodes. The Harvester restaurant, taking its name from its destroyed predecessor, now hosts families attracted by the promise of cheap burgers and the surf ‘n’ turf special, all sure to hold their faces above the sneeze screen at the salad bar, the Perspex roof sheltering the tired lettuce and dumb-cut onion. I once asked a teenage waiter, whose purple acne rose above his collar and across his Adam’s apple, if he knew any detail of the rocket attack. He narrowed his eyes as if I were mocking him. He cleared his throat, shook his head, took my drinks order.

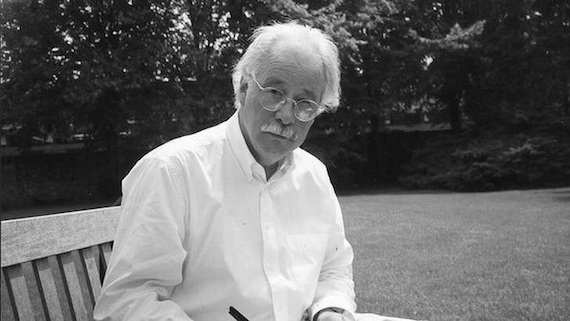

W.G. Sebald was born in the same year that the V2 rocket struck this South London pub. In 1929, his father joined the Reichswehr. It was Ernest Röhm’s desire to merge his Sturmabteilung (SA) with the smaller Reichswehr, its troop numbers limited by the Treaty of Versailles, that provoked the Night of the Long Knives (1934), during which the Nazi regime murdered Röhm, the leadership of the SA, and many other political figures considered a threat to Adolf Hitler’s newly gained power. Arriving in Bromley, I parked the car, a silver Ford Escort, in the South Street car park. A row of tired trees screened the lot from the adjoining road. Having forgotten to bring change, I attempted to pay for the parking ticket using my mobile phone. A bright poster, stuck to the side of the silver parking meter, promised easy electronic payment through a variety of online media. I attempted to download the iOS app, but forgot my password. I was given three chances before my account was locked. There is an absence of technology in Sebald’s work. He wrote in a world coming to terms with the Internet. His first “novel,” After Nature, was published in 1988. His last, Austerlitz, in 2001, the year of his death. Sebald described the impact of dogs on his writing:

W.G. Sebald was born in the same year that the V2 rocket struck this South London pub. In 1929, his father joined the Reichswehr. It was Ernest Röhm’s desire to merge his Sturmabteilung (SA) with the smaller Reichswehr, its troop numbers limited by the Treaty of Versailles, that provoked the Night of the Long Knives (1934), during which the Nazi regime murdered Röhm, the leadership of the SA, and many other political figures considered a threat to Adolf Hitler’s newly gained power. Arriving in Bromley, I parked the car, a silver Ford Escort, in the South Street car park. A row of tired trees screened the lot from the adjoining road. Having forgotten to bring change, I attempted to pay for the parking ticket using my mobile phone. A bright poster, stuck to the side of the silver parking meter, promised easy electronic payment through a variety of online media. I attempted to download the iOS app, but forgot my password. I was given three chances before my account was locked. There is an absence of technology in Sebald’s work. He wrote in a world coming to terms with the Internet. His first “novel,” After Nature, was published in 1988. His last, Austerlitz, in 2001, the year of his death. Sebald described the impact of dogs on his writing:

But I never liked doing things systematically. Not even my Ph.D. research was done systematically. It was done in a random, haphazard fashion. The more I got on, the more I felt that, really, one can find something only in that way — in the same way in which, say, a dog runs through a field. If you look at a dog following the advice of his nose, he traverses a patch of land in a completely unplottable manner. And he invariably finds what he is looking for. I think that, as I’ve always had dogs, I’ve learned from them how to do this.

His books are as strange as his analogy, as charming too. Ostensibly, they are a mixture of fiction, recollection, anecdote, and factual writing. Can we trust Sebald’s words? It doesn’t matter. The fragmented motifs, repeated images, are scattered throughout the texts and sweep you along to a conclusion, at which there magically appears sense to the whole. Verily, the field has been thoroughly sniffed out. I imagine it’s something like listening to a piece of classical music, if I were to listen to classical music. I didn’t sniff my way to Bromley Waterstones, one of the few bookshops in this, the largest of London boroughs. I used Google Maps. From the car park, we walked up South Street and turned right at the larger Tweedy Road. I thought of the album released the previous year by Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy and his son. It’s an album written for Tweedy’s wife, suffering from lymphoma. I can only listen to it when happy. I don’t want my three year old to ask why Daddy is crying, not least because I would struggle to answer the question. On Tweedy Road is the old council building, a cut-price version of Wren’s Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich. There is a stone cupola over the entrance porch. The brickwork, stone quoins and window dressings stick like a fishbone in Bromley’s throat. Its appearance is out of keeping with the corporate iron and glass of the town centre’s commercial units. I try to corral Dylan to stand on the stone steps, thinking of taking a picture. He refuses, pointing to the black grill tight and padlocked across the front doors. This was once the town hall, opened in 1906. It is derelict now, put up for sale 10 years ago. Its listing states that it could be easily converted into a conference centre or split into a series of apartment units. It was Dylan who pointed out Sebald’s name in the fiction section of Bromley Waterstones. That morning, I’d seen Sebald’s name in a review of The Adventures of Sir Thomas Browne in the 21st Century.

His books are as strange as his analogy, as charming too. Ostensibly, they are a mixture of fiction, recollection, anecdote, and factual writing. Can we trust Sebald’s words? It doesn’t matter. The fragmented motifs, repeated images, are scattered throughout the texts and sweep you along to a conclusion, at which there magically appears sense to the whole. Verily, the field has been thoroughly sniffed out. I imagine it’s something like listening to a piece of classical music, if I were to listen to classical music. I didn’t sniff my way to Bromley Waterstones, one of the few bookshops in this, the largest of London boroughs. I used Google Maps. From the car park, we walked up South Street and turned right at the larger Tweedy Road. I thought of the album released the previous year by Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy and his son. It’s an album written for Tweedy’s wife, suffering from lymphoma. I can only listen to it when happy. I don’t want my three year old to ask why Daddy is crying, not least because I would struggle to answer the question. On Tweedy Road is the old council building, a cut-price version of Wren’s Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich. There is a stone cupola over the entrance porch. The brickwork, stone quoins and window dressings stick like a fishbone in Bromley’s throat. Its appearance is out of keeping with the corporate iron and glass of the town centre’s commercial units. I try to corral Dylan to stand on the stone steps, thinking of taking a picture. He refuses, pointing to the black grill tight and padlocked across the front doors. This was once the town hall, opened in 1906. It is derelict now, put up for sale 10 years ago. Its listing states that it could be easily converted into a conference centre or split into a series of apartment units. It was Dylan who pointed out Sebald’s name in the fiction section of Bromley Waterstones. That morning, I’d seen Sebald’s name in a review of The Adventures of Sir Thomas Browne in the 21st Century.

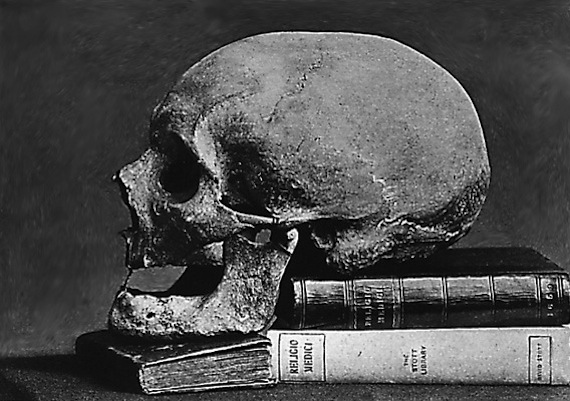

Thomas Browne is a figure that appears in Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn. He was a rural doctor and essayist in the 17th century. He invented the words “medical,” “precarious,” “insecurity,” and “hallucination.” In his writing, Browne asks questions such as ‘Did Jesus laugh?’ I’d mistakenly thought Sebald to be spelt ‘Sibald.’ I’m unsure why. Perhaps I had in mind the character Siward from Macbeth. Unable to find any of Sibald’s books, I was inured to the inevitability of disappointment. Dylan, thick hands full with his Peep Inside The Zoo not yet paid for but quickly granted as it meant ignoring books with rockets or rifles on their covers, said,

Thomas Browne is a figure that appears in Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn. He was a rural doctor and essayist in the 17th century. He invented the words “medical,” “precarious,” “insecurity,” and “hallucination.” In his writing, Browne asks questions such as ‘Did Jesus laugh?’ I’d mistakenly thought Sebald to be spelt ‘Sibald.’ I’m unsure why. Perhaps I had in mind the character Siward from Macbeth. Unable to find any of Sibald’s books, I was inured to the inevitability of disappointment. Dylan, thick hands full with his Peep Inside The Zoo not yet paid for but quickly granted as it meant ignoring books with rockets or rifles on their covers, said,

“Daddy?”

“Yes.”

I traced my finger across book spines. Definitely no Sibald.

“Look.”

Dylan nodded to a book that sat facing forward, at his eye-level, positioned above a “bookseller’s selection” index card. Sebald’s books are full of such happy coincidences. This one was Austerlitz, the winner of many literary prizes, and, as with all of the man’s books, difficult to describe in a single sentence. I pulled out The Rings of Saturn and ushered my son away. Wikipedia describes this 1995 novel as “the account by a nameless narrator…on a walking tour of Suffolk.” And, when insisting friends read it, I compare its structure to clicking through a series of Wikipedia links. Sebald discusses the cultivation of silkworm, he discusses the Boxer Rebellion, he discusses Thomas Browne, he describes searching for Thomas Browne’s skull. He describes eating fish and chips in an empty coastal hotel. It’s compelling in a way that clicking through Wikipedia hyperlinks is not. It’s literary in a way that most “serious” novels aren’t, for Sebald feels no obligation to impress upon the reader his literary ability. Robert McCrum calls Sebald “a wonderful vindication of literary culture in all its subtle and entrancing complexity.” “JimtheRim,” on Amazon, gives the book a one star review, stating “I’ve never read such self-important words. It’s for pseuds. The bok is an intangible mess of nonsense.” Whatever anyone else thinks, I enjoy the time spent with Sebald, a man who insisted upon being called Max because he worried that “Winfried” sounded too much like a woman’s name.

My son fell asleep as I drove us home from Bromley. Peep Inside the Zoo fell from his fingers. Its heavy cardboard banged into the footwell and the sound made me start. It began to rain, the drops drumming against the car’s roof. It wasn’t until I’d finished reading The Rings of Saturn, a couple of days later, that I Googled Sebald and read of his life. He died aged 57. His car, a Peugeot 306, collided with a lorry while negotiating a left-hand bend. His daughter, Anna, was a passenger. She survived the crash with minor injuries. Her father did not. The Norfolk coroner reported that Sebald probably died from an aneurysm before his car struck the oncoming lorry. I felt a strange dissonance on reading all this. Did I remember his death being reported? Had I read of it subsequently? I think the reason for the almost uncanny (unheimlich in German, meaning “un-homely”) sensation is that I’d never read a book so full of life as The Rings of Saturn. It felt a cosmic injustice that a writer who’d invested so much soul in his writing should die so young. Thomas Browne, living in the 17th century, when doctors (such as Browne himself) were as likely to kill you as heal you, lived until 77. I am reminded of Abraham Lincoln, whose death, some say, was aided by the unsterilized fingers of “surgeons” attempting to extract the assassin’s bullet from the president’s brain. I clicked from Wikipedia to Amazon and I bought the rest of W.G. Sebald’s novels. Much as when Netflix releases an entire series of episodes at once, I am resisting the temptation to read Sebald’s books all the way through, pausing only to eat, sleep, and visit the toilet. As long as there remains a sentence, a word, unread Sebald must remain alive. To me, at least. In The Rings of Saturn, Sebald describes how the reader of Browne “is overcome by a sense of levitation.” The same can be said of the reader of Sebald.