Princess Di died on Aug. 31, 1997. I’ll never forget the date — not because I care about the royal family, but because on that day I left my old home in North Carolina, drove 577 miles and moved in with my girlfriend on West 14th Street in New York City’s meatpacking district. My new neighborhood was, to say the least, funky — with sides of beef drooling blood onto the sidewalks, with homeless people camped down by the Hudson River, with hookers working the shadows, and leather boys sporting in clubs called the Anvil and Man Hole. The neighborhood, a little grease stain flanked by Greenwich Village and Chelsea, was also home to a lot of artists and fellow writers. There was no way to know that I had arrived in a neighborhood that was on the cusp of a massive makeover.

Within two years of my arrival, our apartment building got sold, our rent got doubled, and we got bounced. We wound up in a loft in a former doll factory next to a garbage transfer station in Brooklyn. This was during Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s campaign to scrub the city clean, just before he passed the baton to Michael Bloomberg, who spent the next dozen years finishing the job.

A little less than two decades after gentrification pushed me out, I returned to the meatpacking district to attend the press opening of the new Whitney Museum of American Art, which opened to the public on May 1. What I learned at the press opening had little to do with art or architecture, and everything to do with what the new Whitney Museum says about the new New York City. It isn’t pretty.

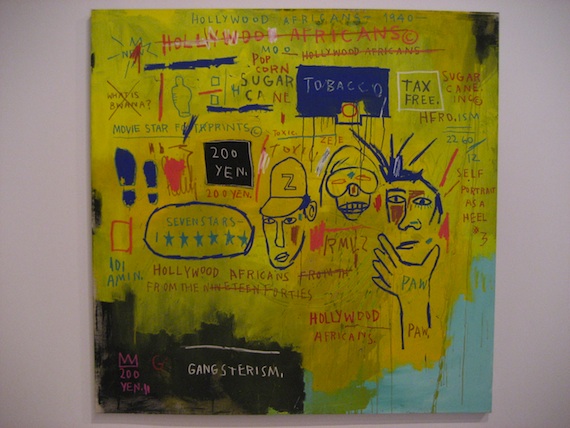

To get the facts out of the way, the new Whitney was designed by Renzo Piano at a cost of $422 million, and it will cost you $22 to get inside to look at the Hoppers, the Warhols, the Lichtensteins, the Basquiats, and the hundreds of other staples from the permanent collection that make up the impressive inaugural show, “America Is Hard to See.” Admission is now $25 at both the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim. Like most of the good stuff in New York today, art is not intended for the hoi polloi.

Renzo Piano is a prolific designer of museums — he did the terrific and very different Pompidou Center in Paris and the Menil Collection in Houston, to name just two — and critics have compared his new building to a ship, a factory, even a hospital. I see an eager-to-please, not-unattractive jumble of blue glass blocks that would have looked laughably out of place in the late 1990s but now fits in with the nearby work of other starchitects — especially Frank Gehry’s twisty glass IAC Building a few blocks upriver, and Richard Meier’s glass apartment towers a few blocks downriver. It also fits in with the trendy restaurants and the shops selling Apple computers and designer clothing. Needless to say, the Anvil and Man Hole have decamped.

The new Whitney was built because Marcel Breuer’s perfectly serviceable building uptown was no longer considered good enough, big enough, hip enough, new enough, or downtown enough. Just shy of its 50th birthday, the uptown building was abandoned like an outdated wife and leased to the Metropolitan Museum. So in addition to being expensive, the new Whitney is unnecessary, a luxury item in a city awash with rich people and their luxury items, a wickedly telling monument to contemporary New York’s get-rich-or-get-out ethos. In that sense, it’s the perfect expression of its moment.

Even its location is telling. Not only does it sit where homeless people and hookers and leather boys and artists used to roam, it sits at the foot of the new High Line elevated park, one of the city’s most powerful tourist magnets, right up there with Times Square and Soho and The Lion King, and Shake Shack. More than 50 million tourists visit New York City every year, and it seems that every last one of them makes a point of contributing to the gridlock on the High Line. This was not lost on Renzo Piano. There’s a floor-to-ceiling window on the fifth floor of the new Whitney that gazes down at the High Line, echoing a window on the High Line at 17th Street that allows tourists to gaze down at the cars whizzing up 10th Avenue. New York City used to be a gnarly, dicey, unpredictable spectacle; now it’s a defanged, tourist-friendly spectator sport. The new Whitney and the High Line are going to make perfect neighbors.

With its commodious gallery spaces, its outdoor terraces and vistas, its interior spaces for screenings and performance, its library, gift shop, restaurant, and café — not to mention its killer collection of American art — the new Whitney is sure to be a success. As an art lover, I have to wish the museum well, though in a bittersweet way. Writing in The New Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl gave the building a largely favorable review before finally acknowledging that such a bauble comes at a cost that has nothing to do with its $422 million price tag. It’s part of the engine that is making New York City increasingly untenable for the creative people who used to make the city spin. Now money makes the city spin.

“The new Whitney won’t do anything to ameliorate the crisis brought about by the crushing cost of living,” Schjeldahl wrote, “which exiles young artists, writers and other creative types to increasingly distant parts of the city, if not out of it altogether. (The museum will actually worsen the problem in its immediate vicinity near the High Line.)”

I can’t imagine it getting any worse. A few weeks before the new Whitney opened I was shopping in the nearby Chelsea Market, where I used to shop regularly when I lived in the neighborhood. I avoid the place now, especially on weekends, because it’s clogged with tourists who will take pictures of absolutely anything, especially themselves. On this day I saw a woman taking pictures of…apples. This was too much. I had to ask.

“Excuse me,” I said. “Where are you from?”

“Norway,” she said, snapping away.

“Don’t you have apples in Norway?”

“Yes, but ours are not this colorful.”

I had a hunch even before I visited the new Whitney that the meatpacking district — that New York City — is long gone. Now I’m sure of it. Me, I’m moving to Berlin.