In a 1992 interview with The Comics Journal, Daniel Clowes talked about the kinds of comics he wanted to draw when he was a teenager.

I remember at the time thinking what a bold concept it would be to just do comics about real people and real life, and that was a real crazy idea at that time. I remember thinking EC was the closest thing to that. Like the Shock SuspenStories, ‘cause it had stories just about people wearing suits, you know; they weren’t in costumes.

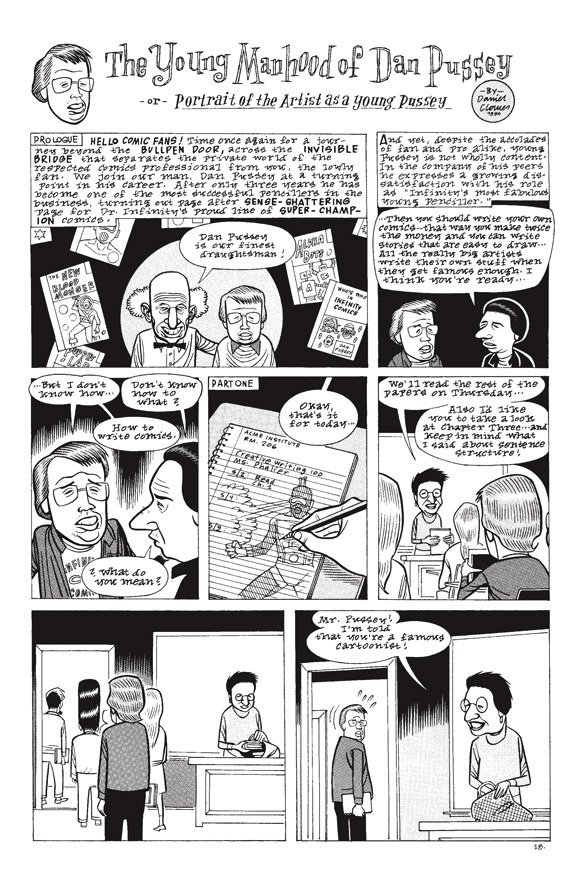

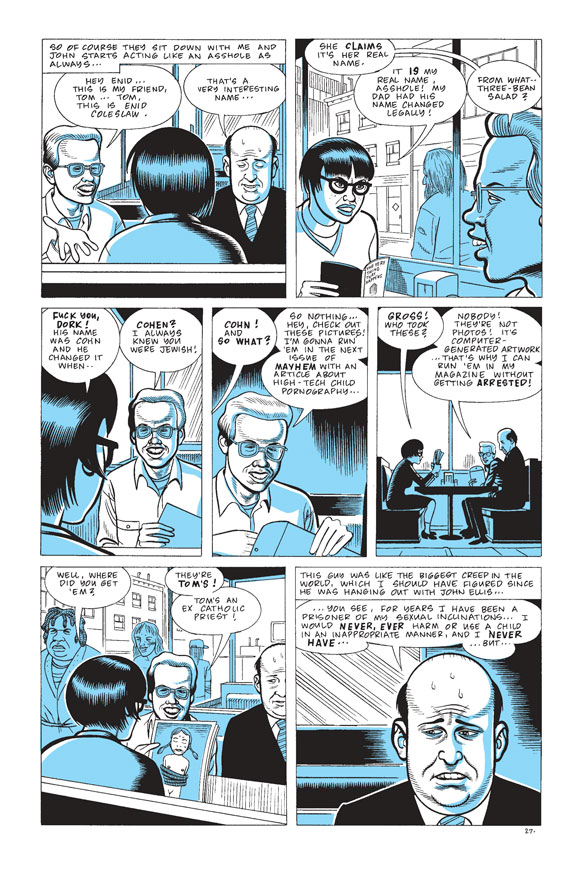

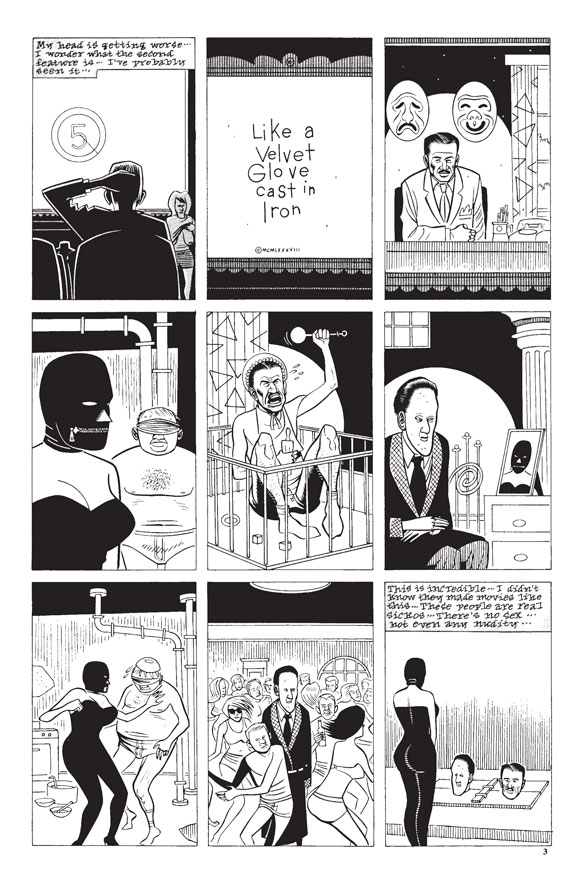

“Suits not costumes” is a low bar for realism, but it laid the basis for Clowes’s own form of grotesquerie. At the time of the interview, Clowes was three years into writing Eightball. The comic serialized his graphic novels Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron and Ghost World and was interspersed with short pieces exercising various registers of tragicomedy. He drew a cruel portrait of Dan Pussey, the pathetic creator of superhero comics. He was far gentler with Enid Coleslaw and Rebecca Doppelmeyer, the grim teenage comic geniuses at the center of Ghost World. I don’t think there has been a fictional character with a better name than Needledick the Bug-Fucker, nor a character who revealed so many multitudes within a single page.

“Suits not costumes” is a low bar for realism, but it laid the basis for Clowes’s own form of grotesquerie. At the time of the interview, Clowes was three years into writing Eightball. The comic serialized his graphic novels Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron and Ghost World and was interspersed with short pieces exercising various registers of tragicomedy. He drew a cruel portrait of Dan Pussey, the pathetic creator of superhero comics. He was far gentler with Enid Coleslaw and Rebecca Doppelmeyer, the grim teenage comic geniuses at the center of Ghost World. I don’t think there has been a fictional character with a better name than Needledick the Bug-Fucker, nor a character who revealed so many multitudes within a single page.

Fantagraphics has just released a handsome two-volume edition of the first 18 issues of Eightball, published between 1989 and 1997. (Later issues were re-released as single-edition graphic novels, David Boring, Ice Haven and The Death-Ray.) We met on April 18 at 9lb Hammer, a bar in Seattle’s Georgetown neighborhood, around the corner from Fantagraphics Books where he was due for a signing. The following is a pared-down version of a 30-minute conversation.

Fantagraphics has just released a handsome two-volume edition of the first 18 issues of Eightball, published between 1989 and 1997. (Later issues were re-released as single-edition graphic novels, David Boring, Ice Haven and The Death-Ray.) We met on April 18 at 9lb Hammer, a bar in Seattle’s Georgetown neighborhood, around the corner from Fantagraphics Books where he was due for a signing. The following is a pared-down version of a 30-minute conversation.

The Millions: It’s clear that Dan Pussey was definitely not someone who read Eightball, but Enid from Ghost World could have [even if she didn’t]. I’m not sure if that distinction is so clear 25 years later.

Daniel Clowes: Probably not, no. Actually I think she and Dan Pussey have merged into one person, the modern reader of comics.

TM: The modern reader of comics has a stack of Spider-Man comics and a stack of Eightball.

DC: There doesn’t seem to be any discernment between types of comics. People who like comics like all comics.

TM: I really enjoy the Dan Pussey comics. But they make me so uncomfortable, because they are filled with so much meanness.

DC: I was so angry. When I first started I was trying to work in this non-existent world of comics that I wanted there to be and didn’t actually exist, which was some version of underground comics. And there were magazines like Raw and Weirdo that were kind of post-underground, [but] there wasn’t that much of that. You couldn’t go into a comic-book store and have this range of stuff the way you can now. And I was stuck in this world that I didn’t feel I belonged to. And then I felt like I was being belittled whenever I went to a comic convention or something. “Oh you do those kinds of comics.” It was sort of like what we did was unofficial. You had to do real comics. You had to do superheroes for big publishers and stuff like that.

TM: So you were angry at mainstream comics culture.

DC: And I was angry…As a young man I could have been Dan Pussey very easily. That was how I got into comics. I was into Marvel Comics like everybody else then. It’s that kind of thing where you move beyond that and then you have an antagonism towards your earlier self. It’s usually expressed in an antagonism towards what you liked at that age.

TM: Have you read Dash Shaw’s series Cosplayers?

TM: Have you read Dash Shaw’s series Cosplayers?

DC: I read the first one, not the second one. It’s good.

TM: I like them because he sympathizes with these abject figures, the current generation of Dan Pusseys.

DC: At the time, I saw myself as socially inferior to Dan Pussey. I was fighting the power at the time, and now I look back and it’s completely the opposite. It seems like I’m making fun of this sad outsider who has absolutely no social bearing in society. At the time, it didn’t feel that way at all. It felt like these are the guys who are keeping me from existing in this world I want to exist in.

TM: Why do you think the comics cultures of Marvel and Fantagraphics merged in terms of their readers?

DC: I couldn’t tell you. It’s a mystery to me. I don’t see any correlation between all the different types of comics. The aesthetic gulf between the kind of stuff I’m interested in and the kind of stuff that is mainstream is so vast that I can’t wrap my head around it. To me, it’s like if you were into two completely different types of music, like if you were into Sam the Sham and the Pharoahs and Mozart.

TM: Which is possible.

DC: It’s totally possible, but the fact that that’s not an isolated weirdo, that it’s everybody…I find very strange.

TM: Well, so much of comics are really about bodies. Superhero comics are about these idealized bodies and the comics that you do are so much about the deformities of bodies.

DC: I would say the reality of bodies.

TM: It’s possible to switch between those interests.

DC: I suppose so, but that’s reading it on a level that is so beyond aesthetic discernment where it’s all about the underlying content of it. I find there’s no qualitative judgment at all.

TM: Your work doesn’t offer any nobility to outsider-ness, no heroism.

DC: No, not heroism. I admire those who are stuck on the outside and have to grapple with that and are really unable to conquer that in themselves. They have some quality that doesn’t enable them to make the leap to the social norm. And I’m interested in characters like that. Heroism, I don’t think so.

TM: You are interested in the idea of a character who is given a condition he has to deal with and chooses to keep existing rather than commit suicide.

DC: Yeah, I find that admirable. I think that’s endlessly dramatic. To me, that’s the most entertaining character, someone who is fighting with himself, who endlessly regenerates the story. A character like Wilson I did a few years ago. I can sit down and think of anything at all. A saltshaker. How would Wilson respond to a saltshaker? And I know in my head I can write a strip in 15 minutes of what he would think: “The salt shaker is the worst designed thing I’ve ever seen.” He’s a perfect example of a character who is unable to be what he wants to be and is unable to cure himself. And I find that endlessly entertaining.

TM: Thanks to the Internet, the notion of freakishness is very different now than it was when you were writing Eightball.

DC: Totally.

TM: Needledick the Bug-Fucker can now go into a chatroom and find people from all over the world who are into the same thing he’s into.

DC: That’s true. I always think to myself, [what would have happened] if I had chatrooms and the Internet when I was 15? Instead of having no way to communicate with anybody, having all this pent-up emotion inside me that I tried to get out by drawing comics, spen[ding] every day of my adolescence really trying to hone that craft so that I could somehow talk to the world…I wonder if instead I would have just gone on some message board and said, “I’m so sad. You too?”

TM: If you could have Googled “I like to fuck small insects” and got back all that information from everyone who did want to fuck small insects, could you imagine writing that story?

DC: No. No. I loved the idea of the world back then. If you had some kind of bizarre fetish like that, it was so hard to meet people who had that same thing. I had a friend, a guy who ran Feral House. He would always find these newsletters about these weird fetishes. These guys were typing up these newsletters and sending them to the three other people they met through this fetish magazine. That’s your whole world, waiting for the new package by guys who are into being stepped on by a woman in high heels. Now you can find everyone in the world who is into that within 15 minutes. I loved that underground.

TM: And that reflects the way Eightball circulated. I read Eightball because of two friends. I’m probably in the last generation of people who would have read it because of word of mouth and not because I looked it up on the Internet. The letters page in Eightball really reflects that fact.

DC: It was absolutely that. That was why I felt the duty to take the letters page seriously. When people wrote to me, I wrote back to every single person back then, because I felt it was my responsibility to be the steward of this little world. And I felt that everyone writing to me and reading me had something in common. They were part of some kind of tribe. And I would send [my readers other] people’s addresses. “You should look this guy up.” The minute I got email I stopped responding to anybody. It just felt like you don’t need me anymore. Eliminate the middleman.

TM: Are there any particular letters that gave you pause?

DC: It’s funny because I saved every single letter I ever got, unless it was some one-sentence, “send me a free comic.” I had file boxes filled with letters. I was doing this monograph a few years ago. And I thought, let’s look through these letters and see if there’s anything interesting. I couldn’t believe it. I just remember nice heartfelt letters. Some of them were 20, 30 pages long, from people writing back numerous times. They put in the kind of effort and energy nobody would do now, [because then] they [had] nobody else to talk to. And I always felt I had to write back with something substantial. It was an amazing outpouring, because I was just this anonymous guy on a certain level, who they felt, “He understands me.”

TM: Did anything from those letters end up in your comics outside the letters page?

DC: Not in specific ways that I remember, but the tone of them absolutely. I felt like I wrote characters based on the voice of some of those letters. I felt like I really knew what somebody talking straight from his id at you felt like.

TM: You once described Eightball as a one-man Mad.

DC: That was the goal, to have a one-man variety magazine.

TM: So you were working with a lot of different voices. How was that different from what was going on at the time?

DC: Robert Crumb was always drawing in an underground comic style. He was always drawing like Robert Crumb. He experimented with different styles, but anyone could spot him a mile away. I was trying to bring in different tones and looks. I wanted some of it to look film-noirish and black-and-white stuff. And some of it was old, 1920s cartoons. I wanted it to be much more over the map. I wanted to see how far you could go with this material and still have all of it make sense.

TM: You didn’t want anyone to be able to identify you.

DC: At the time I wanted to have this completely anonymous style. I wanted it to look like if you had a computer printout of comics where it was totally uninflected with any kind of stylistic stuff unless I wanted it to look in a certain stylistic way. So Velvet Glove was almost photographic in the way I imagined it and now I look back and it looks so intensely stylized. But I think that’s what you’re hoping for in a style, not something you are pitching or trying to make happen.

DC: At the time I wanted to have this completely anonymous style. I wanted it to look like if you had a computer printout of comics where it was totally uninflected with any kind of stylistic stuff unless I wanted it to look in a certain stylistic way. So Velvet Glove was almost photographic in the way I imagined it and now I look back and it looks so intensely stylized. But I think that’s what you’re hoping for in a style, not something you are pitching or trying to make happen.

TM: Why did you want it to be so anonymous?

DC: I wanted to draw the world as I was seeing it in my head. I didn’t want it to be, “Oh, I can draw this kind of thing in this way.” I wanted it to be diagrams of what it looked like in my brain, to filter all that out.

TM: Is that still how you approach your work?

DC: No, it’s much more intuitive. I don’t have to struggle as much, so I feel like I can get into it much more deeply. Back then, I felt like I was just trying to get the basics right, really learning what I was doing. Now I feel like I can do everything without erasing and redoing it.

TM: Maybe it’s because you did the poster for Happiness, but I always thought you had more in common with Todd Solondz than you did with Terry Zwigoff, even though you did two movies with Zwigoff [Ghost World and Art School Confidential].

TM: Maybe it’s because you did the poster for Happiness, but I always thought you had more in common with Todd Solondz than you did with Terry Zwigoff, even though you did two movies with Zwigoff [Ghost World and Art School Confidential].

DC: It’s true. I always wanted to do a movie poster. I always liked the Mad guys who used to do movie posters. I would have done any movie poster. I don’t care about the movie. It could have been an Adam Sandler movie. And I was a huge fan of Welcome to the Dollhouse and to be asked to do his second film…[Solondz] and I have talked and we have a very similar goal. At least my early comics were like [his movies.]

TM: Dan Pussey could easily have found his way into Happiness.

DC: That was the first time I saw Philip Seymour Hoffman. And he was the Dan Pussey I’d been waiting for my whole life. [Happiness] was an ensemble piece, so no one was supposed to be the star on the poster and I said, no, that doesn’t work. I wanted to make Philip Seymour Hoffman the star of the movie. So I made him the focus of the movie and then he was referred to as the star of that movie, which he wasn’t. I always felt like he owed me.

TM: Philip Seymour Hoffman looks like a Dan Clowes character.

DC: When he died, I was crushed because I was 100 percent sure that he would one day play one of my characters. It just felt like one of those paths that had to happen and I just couldn’t take it.

TM: I would like to ask you a couple more questions and if you can’t answer them it’s fine. But Shia LaBeouf…

DC: Oh, I’m allowed to talk about that. I did not sign any non-disclosure agreements. [Shia LaBeouf plagiarized Clowes’s 2007 strip Justin M. Damiano for his short film HowardCantour.com.]

TM: One of the things that interested me in that plagiarism case is not just that he plagiarized your dialogue but that he plagiarized your shots.

DC: Quite a bit of it, it seems. It was close.

TM: The question of plagiarizing shots from one medium to another is a legitimate question, but it still looks like a gray area.

DC: Absolutely. But it was such an egregious case of plagiarism that I didn’t have to get into those nuances. The shots weren’t even so relevant, after the story, basically every line of dialogue and the characters [were plagiarized]. He didn’t even claim that he didn’t use the story.

TM: His behavior came across as so fucked up. Did you think of using him as a character in your work?

DC: No, he’s too specific. I don’t have any interest in getting into any of that at all. But the experience from my end was a very interesting experience and I could definitely see that making it’s way into something.

TM: What made it so interesting?

DC: Just to be a part of such an absurd little thing. I was just getting 10 phone messages from CNN and TMZ a day. People were like, “Could you get to the studio by 4 am?” Everybody was assuming I wanted to be a part of that. And I didn’t want to be a part of that. And I didn’t want to know his name or to have this inflicted on me. [It] was so not funny to me. But if it had been any of my friends I thought it would have been one of the funniest things in the world, to watch one of my fellow artists squirm. I just didn’t want it to be me.