1.

At the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, I loop back around to the beginning of “Matthew Weiner’s MAD MEN,” an exhibition that “explores the creative process behind Mad Men.” I arrived later than I’d hoped, just as the crowds were beginning to bottleneck, and was nudged through the narrow display corridors more quickly than I would have liked. The exhibit is a well-conceived combination of captivating eye candy — Megan’s “Zou Bisou Bisou” outfit and Pete’s plaid pants, Don’s office and the Ossining kitchen recreated in full, embossed business cards from each incarnation of the agency, every item from the Adam Whitman shoebox, a copy of Sterling’s Gold — along with the pen and ink and paper behind all that. I crane my neck behind rows of bodies now three-deep, trying to read an entry from creator Matthew Weiner’s 1992 journal, in which he describes a character for a screenplay he was writing: “He will be brave and cunning but he is ultimately scared because he runs from death and family; for him they are the same.”

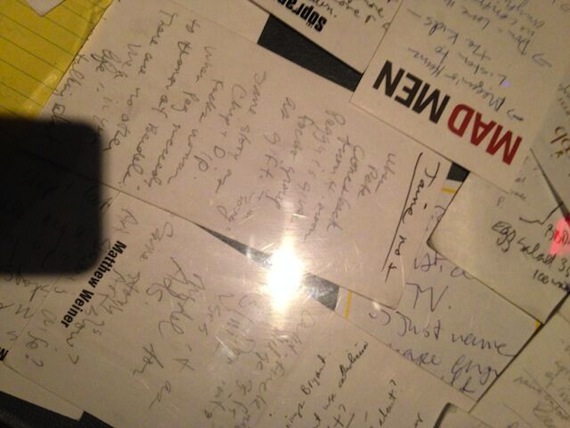

A security guard hovers, scolding anyone who whips out an iPhone before any camera triggers can be tapped. I linger around a standalone display case containing that most romantic of artistic relics — scraps of paper on which Weiner scribbled character, plot, and theme notes whenever they came to him. I wait for the guard to drift to the other end of the exhibit, then hold my phone over the glass and tap-tap-tap, working my way around all four sides and drawing looks. Later I see that the glare and shadows and sometimes illegible handwriting have obscured many words, but I make out a few things, like,

Am I supposed to pretend that I can’t open a jar so you can prove you’re a man

All your lies hit @ once even though you do them one @ a time a

same story as the Chip n Dip

Don seeing a woman / inverse of the pilot

Peggy and Betty have lunch

Fear is contagious. Permeates its expectations.

I’d trekked out to Queens on a Sunday morning — the Sunday of the series finale — because I wanted to somehow mark the end, and begin my pre-mourning. It’s an absurdly dramatic word, I know — mourning — implying real loss. It’s just a TV show, the level-headed inner voice says. But lately I find myself leaning into the gap between rational assertions and a stirring in my gut: yes, of course, It’s just a TV show. So too, When God closes a door he opens a window and I have my health. Nevertheless, experience tells me there may be something interesting, there in the gap, in the dissonance.

As I moved through the exhibit the first time, I found myself surprisingly less interested in the fabulous clothes and mid-century-modern office furniture (although I did love the smudgy worn leather of Don’s Eames desk chair) and more so in these glass-encased scribbles, along with mounted script outlines, the recreated writers’ room whiteboard (a grid of color-coded index cards), and three-ring binders that contained things like “Notes from Tone Meeting.” In other words, the museum curators smartly anticipated what seems to me a real question we’re all left with after spending eight years with Mad Men and now reminding ourselves that It was just a TV show…

We know that we became absorbed, that we experienced great pleasure in watching, and that we couldn’t wait for each new season to begin. We know, or feel at least, that we have participated in something significant, a cultural moment. But what I want to know now, or try to know, is this: Is it art?

2.

I can hear the chorus of responses, falling into three camps: 1.) of course it is, 2.) of course it isn’t, 3.) who cares? Yet for me the question is there, with no obvious answer. And it matters: I believe there may even be moral stakes here.

Our current golden age of TV demands a considerable intensity of involvement from its viewers: when it comes to compelling serial drama, you care a lot about your show and its characters, or not at all. When the subject of Mad Men — or Breaking Bad or The Wire or House of Cards or any number of shows — comes up in a conversation, the parties are typically all in or all out. In the case of the former, the talk zooms zero to 60, whatever conversation you’d started is supplanted; in the latter, with the all-outs, the word “investment” almost always comes up — as in, “I’m not prepared/willing to make the investment.”

Indeed, watching these shows costs; a seven-season, 92-episode show like Mad Men is a significant expenditure — by my math, some 200+ hours (if you’re a re-watcher, as I am). There are myriad other things we could be, should be, want to be doing with our time and energy: how can we not ask, What’s it worth? And I do think about those hours — about the 15 to 20 books I could have read; about the four hours per week for a full year that I might have spent exercising, mentoring a young person, self-educating about global threats, growing food, helping a friend in need, freelancing for extra income, writing fiction, writing letters to my government representatives, calling my mother. Et cetera.

So since the credits rolled on the finale last week, I’ve been thinking less about “what happened” to Don and Peggy and Betty and Joan and Pete and Roger. Or even what happened to American culture, fashion, and gender politics between 1960 and 1970. What I’ve been wondering is what’s happened, over the last eight years, to us. What has the show done to us; what has it meant. Has it done or meant anything? For this is what I mean by that highfalutin word “art” — something that changes me, shows me something that matters, something that will last.

3.

Behind a work of art, there is an artist; and the MoMI exhibition title says it all: “Matthew Weiner’s MAD MEN.” Yes, there is a team of writers, and sometimes they are given due credit. But also (from an interview in The Paris Review):

At the beginning of the season I dictate a lot of notes about the stories I’m interested in. Then for each episode, we start with a group-written story, an outline. When I read the outline, I rarely get a sense of what the story is. It has to be told to me. Then I go into a room with an assistant and I dictate the scenes, the entire script, page by page.

And:

I am a controlling person. I’m at odds with the world, and like most people I don’t have any control over what’s going to happen — I only have wishes and dreams. But to be in this environment where you actually control how things are going to work out, and who’s going to win, and what they’re going to learn, and who kisses who…

And (from The Atlantic):

Much of Mad Men is driven by Weiner’s id, by his own dreams, by what he calls a “wordless instinct,” a conviction that “truth is stranger than fiction.” Some aspects of the show may seem “dreamlike or whatever” to others, but Weiner told me he often experiences things in a very different way than most other people do.

And (from Vulture):

Apparently, one of the actors on The Sopranos said, “My character wouldn’t say that,” and [David Chase] replied, “Who said it was your character?” [Laughs.]…The [actors] definitely thought I was picky and vague, I will say that. I was frustrating to work for because…I’m not always articulate about what I want.

There’s a lot of material on Weiner — he has not shied away from interviews — and I’ve combed only a fraction of it. What I gather is that, as Mad Men gained in acclaim, Weiner gained total freedom: what the characters say and do, the visual, psychological, and emotional tones of the scenes — in the end, it’s Weiner’s vision, and his call. In that sense, he is the Don Draper.

But is the landscape of a writer’s id necessarily artful? We are meant to believe that Don’s creativity works this way — successfully, unquestionably. Does Weiner’s?

In answer to a question about the poems he wrote in college, Weiner said,

[They were p]retty funny, a lot of them, in an ironic way. And very confessional. A lot like what I do on Mad Men, actually — I don’t think people always realize the show is super personal, even though it’s set in the past. It was as if the admission of uncomfortable thoughts had already become my business on some level. I love awkwardness.

That awkwardness, that instinct, truth that is stranger than fiction, that picky vagueness — one might say these are the marks of Weiner’s artistry. When I think back on seven seasons, it’s the weird stuff that floats to the surface: Peggy doing the twist in her awful green skirt toward a glowering, glossy-lipped Pete; Joan hoisting up her accordion and crooning in French; those horrible giggling aluminum-ad twins; Grandpa Gene grabbing Betty’s boob; Lane flaunting his “chocolate” playboy bunny in front of his father then getting beaten with a cane; Ken’s eye patch against his unsettling cheerfulness; Ginsburg’s nipple freak-out; the cringyness I still feel when rewatching Megan’s “Zou Bisou Bisou” performance. These moments felt bizarre, distinctly off, and made me always aware of an authorial sensibility: someone put that accordion in the script, told those girls to giggle, and crafted that palpable awkwardness while Megan flung her hair and legs around.

Why were the characters doing these things? Because Matt Weiner’s dreams, wordless instincts, and experiences said so. “The important thing, for me,” Weiner said, about writing for The Sopranos, “was hearing the way David Chase indulged the subconscious. I learned not to question its communicative power.”

4.

It was Nicholson Baker who once said that he writes best first thing in the morning, before even turning on lights, so he can write “in a dreamlike state.” I always liked the romantic purity of that; and yet, that’s the raw-material part of the process. What next? In undergraduate writing classes, I sometimes introduce the idea of “the moral point of view” — which I borrowed from Anne Lamott’s sometimes cloying but often useful Bird by Bird. Lamott invokes the term moral — with all its baggage — then both deconstructs and reclaims its significance. It’s not about judging characters, or readers; it’s not about black-and-white messages or lessons. It’s about the author having a stake, and exploring/expressing his worldview, lest the work risk being mere craft, bloodless and forgettable. That stake, that world view, could be a pressing, unanswerable question; a hope, or a shade of darkness; an incisive observation about human nature.

It was Nicholson Baker who once said that he writes best first thing in the morning, before even turning on lights, so he can write “in a dreamlike state.” I always liked the romantic purity of that; and yet, that’s the raw-material part of the process. What next? In undergraduate writing classes, I sometimes introduce the idea of “the moral point of view” — which I borrowed from Anne Lamott’s sometimes cloying but often useful Bird by Bird. Lamott invokes the term moral — with all its baggage — then both deconstructs and reclaims its significance. It’s not about judging characters, or readers; it’s not about black-and-white messages or lessons. It’s about the author having a stake, and exploring/expressing his worldview, lest the work risk being mere craft, bloodless and forgettable. That stake, that world view, could be a pressing, unanswerable question; a hope, or a shade of darkness; an incisive observation about human nature.

Is the strangeness of dreams a world view? Life as a series of unresolved and awkward non sequiturs? In Mad Men, people come and people go. They sort of change, but also not really. Many of them behave in disturbing or creepy or inconsistent ways. Ultimately we don’t know the fates of most of the people who come on screen, and neither do the principal characters.

If a young man runs into a beautiful woman at a party on Mad Men and she gives him her phone number and he writes it on a piece of paper and then he loses his coat, he will, on a normal TV show, end up figuring out how to find her. On Mad Men, he will never see her again. (from an interview with Esquire)

This approach unsettles the typical viewer and is likely a main reason — along with its decided racial homogeneity (but more on that later) — the series is not more numerically popular, by ratings standards. I myself have no trouble with narrative non-resolution per se; but it’s hard to know if what Weiner crafts in his episodic world is so much like life that it sometimes seems strange and unreal, or if he’s forcing the weirdness and illogic too hard — manneristically. The young man will never see the beautiful woman again; but will he think of her? Will he care? Does Weiner care? Does he have any stake in it? Should we?

Herein is evidence of a “moral point of view” that discomfits even me, a devoted viewer. Yes, people come and people go, that’s life; but in the world of Mad Men, it doesn’t seem to matter. Peggy’s abandoned baby, and the subsequent easy chumminess of her friendship with Pete (the father) is one example. The inconsequential in and out of so many characters with whom we spend significant time — Duck, Freddy, all of Don’s women (Megan included) with the possible exception of Rachel, Beth, Joyce, Ginsburg, Lane, Ted, Margaret, Hildy, (and what ever happened to Polly the Golden Retriever?!), et alia — is another. There is an uneasy tension between caring about the characters and not caring about them; between them mattering and not mattering. That tension seems to push and pull between the authorial side and the viewers’ side: why is it so easy to discard these broken people? Is it the show that discards them, the nature of episodic TV? Is it Weiner who dictates the emotional reality of the characters out of his own emotional instincts? Or is it, as Weiner would have us believe, real life itself? To be clear, the question isn’t should it matter; the question is does it?

“Get out of here and move forward. This never happened. It will shock you how much it never happened.” These words — Don to Peggy after she has given birth to the baby she didn’t know she was carrying — essentialize Don’s character journey. “You have to move forward. As soon as you can figure out what that is,” he says to Roger over drinks in Season 2. And in the series finale, the words come back yet again, Don to his pseudo-niece Stephanie (with regard to another abandoned baby), slightly softened: “You can put this behind you. It will get easier as you move forward.” Stephanie doesn’t buy it, but for the most part, the principal characters do: they move forward — they both forgive and seamlessly forget — and it’s we who may be shocked by it, not them.

5.

Move forward. Mourning? “Mourning is an excuse to feel sorry for yourself,” as Don made clear to Betty in Season 1. Life is a sequence of episodes, nothing more and nothing less.

In this light, there is a coherence to Weiner’s landing and thriving in the hybrid creative ground of literature and television. He grew up around books — his father carried Marcel Proust on vacation — but he was a slow and “not…great reader,” and had “trouble with long books.” Since he wouldn’t thus be a novelist, he turned to more compressed forms — skits, improv, and then poetry in college. In film school, he found himself a minority among a cohort that “hated episodic structure,” films that were held together primarily by character (e.g. 8 1/2, The Godfather, Days of Heaven). “I liked episodic structure, and I thought it worked. I still think it works,” said Weiner. After film school he started reading more intentionally — biographies, which led to an interest in the “American picaresque character.” When asked about writers who’ve influenced him, he talks about what “holds his attention” — the compact density of poems; J.D. Salinger, Richard Yates, John Cheever.

In this light, there is a coherence to Weiner’s landing and thriving in the hybrid creative ground of literature and television. He grew up around books — his father carried Marcel Proust on vacation — but he was a slow and “not…great reader,” and had “trouble with long books.” Since he wouldn’t thus be a novelist, he turned to more compressed forms — skits, improv, and then poetry in college. In film school, he found himself a minority among a cohort that “hated episodic structure,” films that were held together primarily by character (e.g. 8 1/2, The Godfather, Days of Heaven). “I liked episodic structure, and I thought it worked. I still think it works,” said Weiner. After film school he started reading more intentionally — biographies, which led to an interest in the “American picaresque character.” When asked about writers who’ve influenced him, he talks about what “holds his attention” — the compact density of poems; J.D. Salinger, Richard Yates, John Cheever.

All this may point to a temperament that foregrounds the present moment — layered, discrete, and impermanent — over the long arc or the enduring idea. As a writer in the entertainment industry, Weiner exploits the language and practice of aesthetic concepts, alongside a certain liberty to focus on the internal engine of this scene and these 47 minutes (which will immediately be rated and valuated). The big picture is whatever the aggregate ends up amounting to, not the other way around.

But in Mad Men, this hybridity may have ultimately manifest in a meta-ambiguity (i.e. an artistic ambivalence) that verges on cynical: again, while I am not at all bothered by open-ended ambiguity of plot or character fate — I don’t need to know if Stan+Peggy makes it for the long haul, or even if Don plays out his career at McCann, blue jeans banished forever — I am uneasy with Weiner’s playing both sides when it comes to the art/entertainment handshake. On the one hand, he talks character complexity and “Old Testament flaws” and existentialism, and, according to Hanna Rosin of The Atlantic, is “dismissive of what he calls the ‘Hollywood reaffirmation thing.’” He’s also said: “The term ‘showrunner’ is really foreign to me. It just feels like an agent term. I’m a writer-producer, and the ‘showrunner’ thing takes away the creative part of it.” On the other hand he sometimes ducks behind the “it’s entertainment” curtain, as in, don’t expect or read into this too much, It’s just a TV show. “We’re trying to entertain you,” he said, somewhat irritably, at an event at the 92nd Street Y, in response to a Big Issue question about “men” and “women.” “So, if it seems like it’s about that, you know, that may be what we ended up doing, but that’s not part of the plan.” Similarly, writers André and Maria Jacquemetton said in a 2012 interview, in reference to the show’s relationship to historical research, “we’re making entertainment, not a documentary.”

In other words, Mad Men has aimed primarily to RE-flect, not AF-fect. It’s not “about” anything; it’s just episodes, and they look beautiful and move forward and express awkwardness and sometimes they build toward something and sometimes they veer off, and dead-wood characters drop off as instinct dictates, and now…well…now it’s over. If you expected something more, dear viewer, something “that will last,” then that’s your own silly problem. After all, Weiner and company would say, we’re making TV here, not the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. “Love was invented by guys like me, to sell nylons.” We’re just selling programming here, not meaning.

6.

But c’mon; really? If advertising is metaphor, then the show is the meta-metaphor? Self-consciously shallow and deceptively complex? It feels like a fake gotcha, a feigned cleverness that may actually be a smokescreen for hedging. When Lili Loofbourow writes (at the Los Angeles Review of Books):

I do think it’s very much to the show’s credit that it ends with an ad — showing how monumentally frivolous its guiding vision has been all along. I appreciate that. I do. It’s even a certain kind of brilliant. It’s just not something I, personally, can love —

I’d like to agree about the brilliance — that it’s all been a masterful trick, and the joke’s on me. But that would mean that the writers genuinely cared very little about the characters, while doing their damndest to make sure that the viewers did. And that is contempt and cynicism of quite a high order. It seems more probable that in the particular way the show hedged art and entertainment, it copped out; it settled in the end for being the head-turning bombshell at the gala, relying on her cleavage instead of her Mensa IQ, tragically underachieving.

Because the characters did matter to us; but then — and now we come to the finale — they kind of didn’t. We believed in Peggy, in her unlikely ambition and talent, her quirky beauty and capricious taste in men, and her oddness; in the end, as she rises in the professional ranks, she really just wants a corner office at McCann and to work on Coke and to channel a Sally Albright she predates by 20 years. We felt for Joan through her ups and downs and admired her plucky, hip-swinging sensuality; what she loves, it turns out, in lieu of male bullshit and yet still uninterestingly, are making money and wielding power, like an extended middle-aged revenge fuck. We expected little from Roger and Pete, but we enjoyed them (except when we didn’t), so I’d say we’re at zero-sum seeing them keep on, more or less as they were. As for Betty, it seemed fated since the pilot that someone would kick it from too many Lucky Strikes, and she was the one at odds with her body all along; her clarity and muted emotion at the end were for me the most satisfying — character-logical — of anything that happened in the finale.

As for Don — Don whom I have admired, despised, defended, quoted, and rooted for most of the time — it turns out he’s an ad man; that’s what he is. To boot, he’s not so special, really. He’s been cruel and honorable, weak and strong. He really needed a hug — and he finally gave it to himself, via lonely Leonard and hippie self-help — and now he can do as he’s told others to do, i.e. Put It All Behind Him. In the penultimate image, Don’s gleeful face is huge on the screen, outsizing his trail of wreckage times a million. And nothing much matters now, because the episode, and the series, and the characters, have come and gone. We thought there was some there there, and I think the writers did, too (see my end-of-season-7-part-one essay, in which the Burger Chef episode as possible series finale had me singing a very different tune); but then there wasn’t. Because if you hedge long enough, you’ll tip right over. It doesn’t take much, just a feather-like waft, or maybe just silly viewers and their need for meaning.

The writers would surely say that the characters’ endings came organically from “who they are.” But I’m not really buying that, because Weiner, as creative non-showrunner, has been imprinting who he is, his authorial dreams and awkwardness and moral point of view, all along. The notion that what Mad Men does is more like real life than what other TV shows do is perhaps the most self-unaware thing that Weiner asserts, and suggests, again, some hedging: is he the show’s creator, or is he simply managing life-like characters’ inevitable behavior? The characters’ stunning disconnection from their actions and interactions — the atomized non sequiturs that comprise their stories — is a highly particular version of real life.

I think, for example, of the Season 5 finale of The Wire — in which the dark fate of a promising young black male (Randy) resulting from the carelessness of a dull-witted white male (Herc) is not relegated to the dead-wood pile of episodes past, but revisited and shown to the viewer; surely David Simon would say, That’s real life, and fuck yes it matters. I think too of the very satisfying series finale of Friday Night Lights, in which the saintly and sacrificial Eric and Tami Taylor finally make a selfish choice, and what we feel in those heartbreaking final moments is how everything that is now off-screen — everyone from the past five years from whom they have disconnected and put behind them — matters so very much.

7.

As is obvious by now, I did make the investment; I ponied up big and bought what Mad Men was selling. So invested was I that I may still have been convinced of Weiner’s all-in artistry, or Loofbourow’s theory of visionary brilliance — if it weren’t for Weiner’s final words with regard to the finale. Moved to speak out after the fact, in response to what he thought were disturbingly cynical readings of the ending, Weiner explained that the implication of the episode’s final images is that Don, “in an enlightened state…created something that’s very pure,” i.e. the most famous ad campaign in history, “Buy the world a Coke.” In other words, Weiner exults in Don’s transcendent talent, and his receptivity to artistic vision via emotional healing. In apparent earnestness, Weiner takes a final shot at resonance by celebrating the artist and the possibility of human wholeness.

But what to make of an earnestness so blind to — so disconnected from — what it means? As we now know — thanks especially to Ericka Blount Danois writing at Ebony — in real life, Billy Davis, an African-American man who’d had a career as a songwriter and A&R executive, was the music director at McCann Erickson in 1970; he helped to create the Coke campaign and co-wrote and produced “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing.” The campaign, as the Coca-Cola Company tells it, was a team conception; but as Tim Carmody points out at The Medium, it was Davis — one of the few African Americans at the senior level in advertising at that time — who contributed what might be described as “pure” or “enlightened” — the part that involved harmony and healing. Davis said to Bill Backer, creative director for the Coca Cola account:

Well, if I could do something for everybody in the world, it would not be to buy them a Coke…I’d buy everyone a home first and share with them in peace and love.

Does it matter that Weiner gave Don Draper credit for the ad? Does it mean anything? Carmody said it well:

We have a long tradition in the United States of erasing the creative work of black Americans, of suggesting that the inventions of black men and women either came from nowhere, came from no one in particular, or were in fact the creations of white people. We do this in our history, in our oral traditions, and even in our fiction.

Mos Def had something to say about it, too:

Elvis Presley ain’t got no SOULLLL (hell naw)

Little Richard is rock and roll (damn right)

You may dig on The Rolling Stones

But they ain’t come up with that shit on they own (nah-ah)

I wonder if Loofbourow would say that it was all ironic meta-brilliance on Weiner’s part: in Mad Men’s final act of meta-metaphor, the white man gets full credit for a black man’s work — work of lasting greatness — so that we can be properly entertained. I think I prefer blinded earnestness; the joke grates like fingernails on a chalkboard. Maybe Chris Rock could pull it off; Matthew Weiner can’t.

One of the last installations at the MoMI exhibit is a screen display of the various opening credit sequences submitted by the design firm Imaginary Forces. It’s impossible to imagine a different choice from the iconic falling silhouette we’ve come to know so well: the sequence is beautiful, haunting, racy; and like a great first paragraph of a novel, it contains the whole of the story to come. The mysterious ad man’s ephemeral surroundings crumble around him; he falls and falls, it’s terrifying but also exhilarating; then he lands. Reclined, unruffled, and still smoking.

You win, Don Draper. You always do. It would seem that I am ready to move forward, and to put Mad Men behind me like it never happened.