I thought of Shirley Jackson’s short story “The Lottery” as I watched the opening sequence of Ex Machina, a new film by Alex Garland. Caleb, played Domhnall Gleeson, peers into his computer in a techy looking office. He receives a message that he has won a lottery. As text messages pour in to congratulate him and co-workers clap his back, a look settles onto his face. Just as the opening of “The Lottery” glorifies our pastoral past too perfectly with flowers, “blossoming profusely,” Caleb, lit by the glow of his screen, seems to question. In a post-Edward Snowden world where our identities are tracked and online movements are monitored, is there such thing as random selection?

After his win, Caleb is flown by helicopter to a remote spot in the mountains and told to follow the river, which isn’t easy with a rolling suitcase. He finds the house of the CEO Nathan, played by a perfectly hollow-about-the-eyes Oscar Isaac, and is asked to sign a non-disclosure agreement. Nathan’s house is actually a high tech research facility and Caleb has been brought in to conduct a test of a machine’s intelligence ability to pass as human, a Turing test. The rest film is structured around Caleb’s testing of Nathan’s artificial intelligence, Ava.

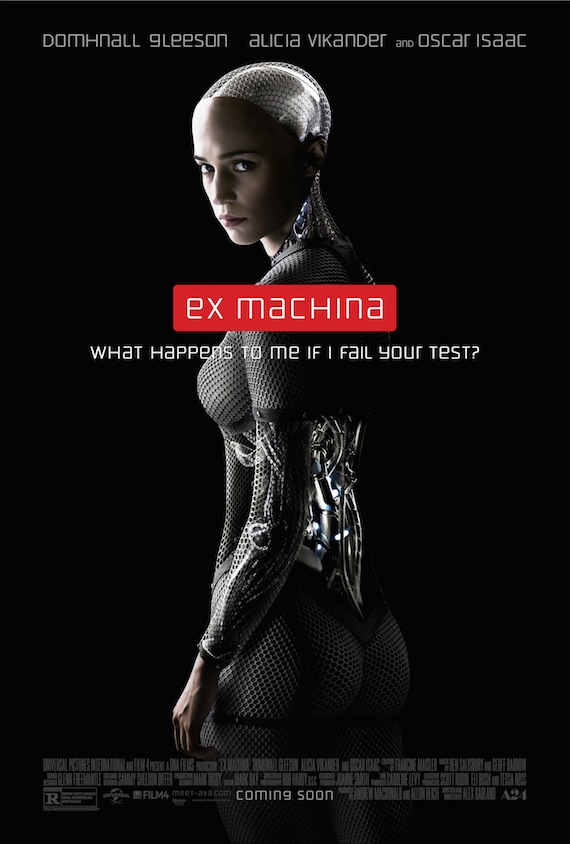

Ava, in a subtle performance by Alicia Vikander, is visibly robotic, though parts of her have soft, perfect skin. Her arms, legs, and waist show her mechanics, shaped curves hug her breasts and bum. When I first saw her, with my tongue in cheek I thought: Ah, a female character reduced to the important parts. And in this kind of reaction lies the cleverness of this film. It plays out as a test of theory of mind, or “awareness of mind” as the film calls it — the ability to understand your own beliefs, intents, and desires, but also to understand that someone else has a different set of the same.

Robin Dunbar, a British evolutionary psychologist who specializes in primate behavior, studies how we hold several people’s intentions in our minds at the same time. In his book, Lucy to Language, he uses the example of Othello, that the plot requires audiences to understand, “that Iago intends that Othello imagines that Desdemona is in love with Cassio.” William Shakespeare requires the audience to understand four levels of mental representation. He raises it to a fifth level when, “Iago is able to persuade Othello that Cassio reciprocates Desdemona’s feelings.” To Dunbar, that is how Shakespeare weaves a narrative spell.

Robin Dunbar, a British evolutionary psychologist who specializes in primate behavior, studies how we hold several people’s intentions in our minds at the same time. In his book, Lucy to Language, he uses the example of Othello, that the plot requires audiences to understand, “that Iago intends that Othello imagines that Desdemona is in love with Cassio.” William Shakespeare requires the audience to understand four levels of mental representation. He raises it to a fifth level when, “Iago is able to persuade Othello that Cassio reciprocates Desdemona’s feelings.” To Dunbar, that is how Shakespeare weaves a narrative spell.

Ex Machina works on a similar level. Without spoiling the plot, the fun of the film lies in that Nathan intends that Caleb imagines that Ava is or is not feeling about Caleb, who may or may not believe Nathan. Kyoko, Nathan’s servant becomes involved, the plot gets another twist.

Dunbar makes an interesting point about writing. Most of us can follow to the fifth level of intention and enjoy a good story. However, far fewer have the ability to compose an interesting tale because the fifth level is most people’s natural limit. The ability to work at the sixth level, what makes a really interesting story, is rare. Shakespeare was able to, “intend that the audience believes…” Garland also successfully works a level higher and this is where the film soars. In taking and subverting current ideas about gender, sci fi, and the thriller genre, he gives us a sharp tweak and delivers a film about theory of mind that is deliciously hard to read.

Garland is author of The Beach, a novel that defined the darker side of backpacking in the 1990s and later became a movie staring Leonardo di Caprio. His next novel, The Tesserat, was called “taut, nervous and often bloody,” by The New York Times and was an early sign of his willingness to play with structure. He wrote the script for Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later and adapted Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go for the screen.

Garland is author of The Beach, a novel that defined the darker side of backpacking in the 1990s and later became a movie staring Leonardo di Caprio. His next novel, The Tesserat, was called “taut, nervous and often bloody,” by The New York Times and was an early sign of his willingness to play with structure. He wrote the script for Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later and adapted Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go for the screen.

As an Ishiguro fan, I asked Garland about adapting Never Let Me Go. He was able to form an accurate belief about my intentions and said he felt “an acute sense of duty.” He had moments where he wondered why he could not just leave it as a novel, but, as with any project he works on, “it’s not a calculation, it’s a compulsion. You do it because you have to.”

With Ex Machina, Garland wrote the script and directed the film as well. At first he said it was a bigger step to go from novelist to screen writer, whereas moving from writing to directing felt smaller. The more we talked, however, the more Garland came around to seeing his work in novels and on the screen as very similar: “You start with a blank page. You engage the imagination. The problems of how it hangs together are the same.”

Like the best short stories, Ex Machina is sparse, taut, and precise. Every word of dialogue has weight and each shot has a purpose. As with Jackson’s “The Lottery,” the film ultimately shows the power of thinking about what we are doing and why. While the action in Ex Machina shifts in sharp pivots, many of the scenes play out almost as if they are on the page with Caleb and Nathan debating the philosophical implications of artificial intelligence. In other words, it’s fascinating.