This post was produced in partnership with Bloom, a literary site that features authors whose first books were published when they were 40 or older.

1.

Sometimes being a Bloomer isn’t so much about the dazzling late first act, as it is about the fact that there is a second act at all. Viv Albertine joined the all-girl punk group The Slits in 1977, when she was 22, and played with them until the band’s demise in 1982. Hers was an early and well-documented success, a confident measure of stardom and swagger in the early days of the British punk scene — certainly enough to disqualify her as a Bloomer.

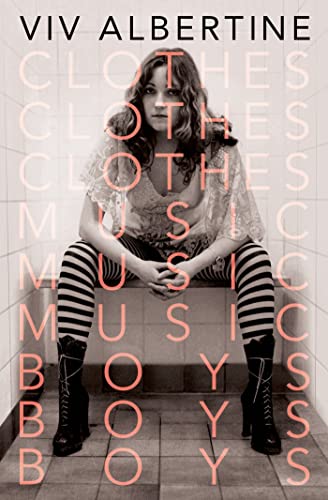

But the act of blooming doesn’t always follow a single trajectory. And her dogged drive to recreate herself as a musician — and to redefine herself as an artist — didn’t truly take form until she was in her 50s. Some have bloom thrust upon them; Albertine has earned hers, every step of the way. And her account of that process in her recent memoir, the wonderfully-titled Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (St. Martin’s Press, 2014), is both honest and deeply satisfying. And, yes — punk rock.

2.

Those of us who came of age musically at a certain time in the world will be put at ease immediately by the book’s divisions: Side One and Side Two, like an album, or maybe a cassette tape. And like any good album, Side One is front-loaded with the hit singles, the stuff the DJ is going to play to win her listeners over. It’s punk rock dish of the highest order: Albertine is in a band with a pre-Sex Pistols Sid Vicious when he was just shy, gawky John Beverly; dates Mick Jones from The Clash (who wrote “Train in Vain” about her after they broke up); shops at Malcolm McLaren’s iconic King’s Road shop SEX, and says of The Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde, who had her eye on Albertine’s future spot in The Slits, “But they wouldn’t ask Chrissie. No one wanted to be in a band with her, she’s too good.”

She picks up a guitar because that’s what a music-loving art school girl does, with no illusions about becoming a musician. “Mick and I go to Denmark Street to choose a guitar. I’ve got no idea what to look for. I might as well be going to buy a semi-automatic weapon.” What Albertine has is gumption and the particular musical zeitgeist of mid-’70s London, where one doesn’t need musical talent so much as attitude:

I’m trying to be a musician in front of all these new people, a very bold move as I can’t play guitar and haven’t written any songs. Sometimes I think I might as well say, “I want to be an astronaut.”

The other thing any self-respecting punk rocker needs, of course, is an aesthetic — the visual kind, and a lifestyle aesthetic as well, a certain ethos that, if lived whole-heartedly, results in an actual level of credibility. Albertine has both in spades, and The Slits — along with singer Ari Up, drummer Palmolive, and bassist Tessa Pollitt — end up making a little slice of musical history. They are unapologetic, balls-to-the-wall, wild women, in the right place at the right time, and their influence reverberates across the next 30 years: the Riot Grrrl bands, Björk, Sonic Youth, and even The Go-Go’s cited them as influences.

If this were Behind the Music, or even the story of poor misunderstood John Beverly, we know what form this story would take. But Albertine is never much of a druggie, not even a drinker — for all her youthful rebellion, she still cares about upsetting her mum. She’s smart, with a strong streak of self-respect (and a small one of prudery), all of which serve to keep her from getting carried away in the undertow of those dangerous days.

But still, there are forces at work that can undo even — perhaps especially — a smart girl who cares about her mum. Which brings us to Side Two.

3.

After The Slits break up, Albertine moves back home. She teaches aerobics for a while, goes to film school, directs some videos. Along the way she falls for a handsome motorcyclist she meets at a party and marries him. Gets pregnant, loses the baby, and embarks on a long, excruciating course of fertility treatments and in vitro fertilization; this chapter of the book, appropriately, is titled “Hell.”

Eventually she carries a daughter to term. Three months after giving birth, she is diagnosed with cervical cancer. She survives that too. It’s a harrowing bit of reading, all the more so because Albertine stays away from hyperbole; the big moment in her recovery comes when she finds herself sweeping her kitchen floor:

I don’t remember deciding to sweep the floor, getting up and going into the kitchen, I just notice that I’m doing it. I used to enjoy sweeping up, it was the only household chore I liked. I remember thinking to myself when I was well, Poor old Madonna, never gets to sweep her own floor, someone does it for her, she doesn’t know what she’s missing. I think there’s something very healthy about keeping your own cave clean…As I sweep, I realise that this is the first time for a year I’ve felt motivated to do anything that’s not absolutely necessary, and I know that a little shift has occurred. It gives me hope that maybe, if more little shifts start to happen, I might get better.

She, her husband, and the baby move to a beautiful white house by the ocean. And there she languishes as her marriage stagnates, and Albertine finds herself living out a story more Henrik Ibsen than VH-1.

But Albertine is still the same woman who allowed her life to be changed once by the impulse to pick up a guitar; this time, by sweeping a room. Like a dowser, she is good at following her own instinctive movements one way or another. A long-distance flirtation jars her out of her somnolence; ultimately unconsummated, it nevertheless has the power to remind her of her own dormant life force. “You know how it is when you meet someone new, someone you admire or fancy: you imagine them watching you and you glide about, a superhero in your own little universe…I’ve found someone who gets me.”

Albertine picks up her guitar again. This time, she decides, she will learn how to play it. And she does — slowly, often agonizingly. She recruits a girlfriend to accompany her to the local open mic nights where, she admits, she is terrible at first. But she keeps on with it, and improves, week by arduous week.

Here, too, is the reader’s reward for having stuck with her through the chapters on infertility, cancer, unhappiness. Following Albertine as she accomplishes what she has set out to do, gets better at it, divorces her husband, and eventually records an album and goes out on tour — it’s good to know this kind of thing can happen, and that it happened to a person like Viv Albertine. By the time Side Two winds down, the reader — this reader, anyway — is a little smitten with her honesty and sweet, genuine voice.

Carrie Brownstein, the guitarist of Sleater-Kinney — another seminal all-female rock’n’roll band, formed a dozen years after The Slits broke up — wrote in Monitor Mix of Albertine’s 2009 solo gig opening for the re-formed Raincoats in New York:

at the Knitting Factory on Friday, watching not The Raincoats (who were fantastic, by the way) but Viv Albertine, I realized I hadn’t really witnessed fearlessness in a long time, at least not at a rock show. As one of my friends put it, more succinctly: “This was one of the punkest things I have ever seen.”

If there is a voice in music that’s seldom heard, it’s that of a middle-aged woman…A woman who isn’t trying to please or nurture anyone, but who instead illuminates a lifestyle that’s so ubiquitous as to be rendered nearly invisible…It raises questions that no one wants to ask a wife or a mother, particularly one’s own. Are you happy? Was I enough? What are you sacrificing, and are those sacrifices worth it?

In her new album, The Vermilion Border, Albertine sings about very different concerns than she covered in her years with The Slits: motherhood, marriage, middle-aged sex, and cooking. She shreds like a teenager playing air guitar in front of her bedroom mirror and she swears like a sailor, but through it all you never forget she’s a 50-something-year-old woman with a very real history behind her. And that…that is punk rock indeed.

In her new album, The Vermilion Border, Albertine sings about very different concerns than she covered in her years with The Slits: motherhood, marriage, middle-aged sex, and cooking. She shreds like a teenager playing air guitar in front of her bedroom mirror and she swears like a sailor, but through it all you never forget she’s a 50-something-year-old woman with a very real history behind her. And that…that is punk rock indeed.