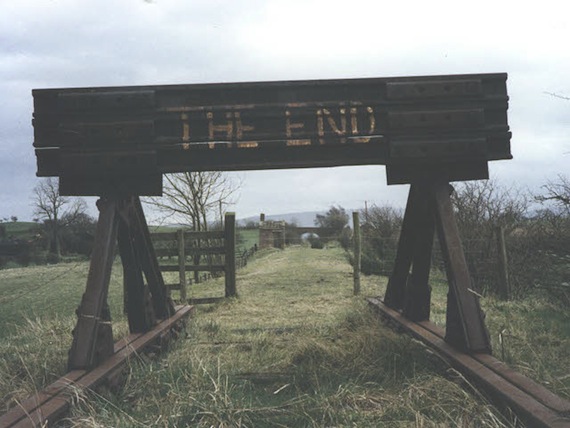

Writing the final pages of a novel is difficult enough, but then comes the final challenge. It’s the end of the end, the last stop on the line, the dazzling dismount: a damn good closing sentence.

I finished my novel while sitting in a movie theater, watching a documentary on light pollution. I’m not sure what it was about The City Dark that helped me get there. Maybe it was the documentary’s eerie central question — Is darkness becoming extinct? — or perhaps it was the church-like quiet of the theater. Maybe it was that, in my utter absorption, I’d for once stopped thinking about the novel. Whatever it was sent me scrambling for a pen and a receipt and then, when I couldn’t find either, repeating one line in my head like a mantra: I knew there was nobody watching me. I wasn’t sure that it was elegant, or even grammatically sound, but I did know it was just how my narrator — who spends the novel negotiating issues of privacy and voyeurism — would want the book to end. Grammatical or not, it was my last line, and I was sticking to it.

Read on to see how six authors found theirs.

1. Rufi Thorpe, author of The Girls from Corona del Mar

1. Rufi Thorpe, author of The Girls from Corona del Mar

For my debut novel, The Girls from Corona del Mar, I had no idea what the last lines would be and finding the ending was kind of like fencing by yourself in a giant gymnasium in the dark. I just kept writing and writing. Where was it? It had to be around there somewhere. There couldn’t NOT be an ending. I parried and thrusted and eventually I found an opponent in the darkness and somehow the damn thing got written, but it was not graceful. It was an awkward and sweaty process. Clearly there had to be a better way.

John Irving, of whom I am an ardent and really inappropriately effusive fan, claims to start with his last scene first and then write the whole novel toward it. How elegant, I thought. What a beautiful way to work. So that is what I attempted with my second novel, which Knopf recently bought and which will come out, you know, eventually. So I wrote the final scene of the book first, and then I started at the beginning and I wrote toward it. This is not as easy as it seems! The book, like a sewing machine going too fast, kept veering off in unexpected directions, taking huge looping digressions. And yet, what was there to do but follow where the characters led me? When I write, I tend to write a lot and then discard a lot, and so I patiently followed my characters and eventually, low and behold, they wound up right where I had started, at the ending I had chosen for them in the beginning. I added one extra scene-let, more of a coda really, and then that was it, but mainly because it felt somehow incorrect to end a novel on an airplane. You have to land, right? You just have to. So I let them land, and then that was it: the trip was over.

In the end, I am not sure one strategy is actually more effective than the other, and both cause a tremendous amount of anxiety. In the first case, you are terrified there is no ending and your characters will just continue on like Schrödinger’s cat, half alive and half dead, with nothing at all resolved. But in the second case, you doubt constantly that the ending you initially chose was the right one. What if you are forcing your characters into actions and behaviors that no longer make sense for them? What if their destiny is no longer their destiny and you are just like a bad matchmaker trying to force through an arranged marriage out of pride? So far as I can tell, there is no best option, and in fact part of how you know you have finished a novel and that the ending you have found is the ending you were meant to find, is that the entire process is awkward and sweaty and appalling and at the end of it you vow never to do it that way again.

2. Meg Wolitzer, author of Belzhar

2. Meg Wolitzer, author of Belzhar

My character’s name is Jam, and she’s been sent to a boarding school for “emotionally fragile, highly intelligent” teenagers, because she cannot get over the tragic loss of her boyfriend. It’s revealed early on that this boy once gave Jam a jar of his favorite kind of jam. Throughout the

book, she says she will never open the jar; doing so would be letting go of her love for this boy and everything they had together. I will get to the last line, but to give it context I first have to mention what comes right before it. The very end of the book reads:

‘This stuff is supposed to be pretty good,’ I say, and then, trying to look casual, I grasp the lid of the jar and give it a turn. It makes a surprisingly sharp pop, as if it were releasing not just air, but something else that’s been dying to get out for a long time.

Then I sit cross-legged on my bed, leaning against the study buddy, facing DJ, and with a slightly bent knife stolen from the dining hall, I spread some of the dark red jam on a couple of crackers—one for her, and one for me. When I put mine in my mouth, the sweet taste startles me. I let it linger.

I let it linger. I was excited to write that very last line; it felt right, coming after the description of opening the jar, which is a big deal for the narrator. The last line serves as a kind of coda, a way to hold on to what’s just happened — to give not only Jam a chance to see that her action matters, but that its effect will have some staying power. This, of course, is what all writers want their readers to experience; we hope that, somehow –– at least for a little while –– the words will linger.

3. Adelle Waldman, author of The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.

3. Adelle Waldman, author of The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.

I struggled a lot with the final chapter of Nathaniel P., last line included. I worried about being too heavy-handed, inflecting the ending with too much of my own point-of-view. Although I definitely favor a certain reading, I tried to refrain from any overt signaling of what I think because I wanted to remain true to the book’s character, Nathaniel. The last line reads:

He’d no more remember the pain — or the pleasure — of this moment than he would remember, once he moved into the new apartment, the exact scent of the air from his bedroom window at down, after he’d been up all night working.

I wanted the line to be ambiguous in its meaning, to convey a feeling that is acute and earnest but can nonetheless be interpreted as the fleeting nostalgia of the moment — something that can be forgotten without consequence — or something more important, the kind of deeper truth that can be inconvenient and unsettling and which we might prefer to bury under the chaos of day-to-day life. I think such ambiguousness is true to life: as we go through our lives, we rarely know how to read what we feel, how much weight to put on this or that passing mood. I wanted the novel’s presentation of psychological and moral life to be as complicated and prone to shape-shifting as our actual private lives.

The line also contains a nod to another book, but this is so subtle — practically imaginary — that it’s for myself rather than because I expect anyone else to see it. For me, the reference to the smell of morning from a window recollects a scene in George Eliot’s Adam Bede. The charming, handsome Arthur Donnithorne has spent the night worrying about a romance he started in spite of his better judgment; he resolves to end the relationship before it goes too far. But when he wakes up the following morning, to a lovely day, and breathes in the fresh morning air from his window, his late-night anxiety seems overwrought. He puts aside as melodramatic the resolutions he made. In the course of the novel, it turns out he was right to be worried; it was the cheerfulness and bustle of day that was misleading. I think this scene is incredibly perceptive about how people, myself included, actually behave, and I liked the idea of calling back to it, ever so subtly.

4. Ted Thompson, author of The Land of Steady Habits

4. Ted Thompson, author of The Land of Steady Habits

I wrote many, many drafts of this novel and each had a different ending, and a different final sentence. Some were mean and cutting, some were attempts at hopefulness, some were vague in a way I hoped a reader would make sense of (since I certainly couldn’t), and all of them were overthought. I was trying so desperately to control the readers’ experience of that final moment that I forgot about the characters and the story. Somehow, with final lines, it’s so often impossible to separate from them my own feelings about the work as a whole, so that I find myself trying to cram as much meaning as possible into a single sentence, trying, I suppose, to redeem the project from all the ways it has fallen short of what I’d hoped it would be.

So how did I find a final sentence I was satisfied with? The short answer is that I ran out of time. We were supposed to leave on our honeymoon the following day. It was summertime, August, and we were visiting my parents in northern New York. Everyone in my family was outside in the sunshine and I could hear them through the open windows laughing and chatting, occasionally someone diving into the pool, and everything inside me wanted to be out there with them. But the novel was a year overdue, and somehow I couldn’t bring myself to leave on this trip knowing that the cloud of this book — and all its subsequent distractions — would follow us onto our honeymoon. So I sat at the desk in that bedroom writing and rewriting the final paragraph by hand. I wrote it and scratched it out and rewrote it, added arrows and clauses, read it aloud to myself again and again, trying to listen for the right feeling. Finally, as the afternoon sun began to change, I knew everyone would soon be headed back inside, so I said to hell with it. I typed it into the manuscript and emailed it to my editor. Then I went outside, announced that I had finished, and went swimming.

5. Michelle Huneven, author of Off Course, Blame, Jamesland and Round Rock

5. Michelle Huneven, author of Off Course, Blame, Jamesland and Round Rock

In three of my four novels, I knew well before I was halfway done what the last line was going to be. In fact, I wrote to those last lines. I had to see my way clear to them. They pulled me through. In my fourth novel, Off Course, I didn’t know the last line and I overwrote the ending by 20 or 30 pages. (Sometimes a book just ends, no matter how hard you try to tack on something else). Only after cutting those pages and packing what I could use from them into the preceding chapters did I locate my last line in a serviceable, finalizing bit of exposition. Who knew?

My favorite last line comes from my second novel, Jamesland.

Jamesland begins with 30-something Alice Black waking up in the middle of the night to find that a deer has come into her house. She chases it out and goes back to bed, but in the morning, she can’t tell if the deer was a dream or a fact. Either way, she’s sufficiently disturbed to discuss the event with various people, including a minister who suggests that Alice look into what deer might mean to her. In her own inadvertent way, Alice does look into this. She learns, for example, that in Buddhism, the deer is a symbol for listening; in Persian carpets, the deer is a symbol of worldly cravings; in the Psalms, the deer thirsts for water like the soul thirsts for God, etc. You might say that deer become a vehicle for meaning in Alice’s life. Although she never pins down what, specifically, deer “mean to her,” her whole life changes as she pursues the question.

One thing that happens is, she takes up with Pete, a chef who, at the end of the novel, has just opened a new restaurant. On a cool, winters day before the dinner shift starts, he’s walking up through Griffith Park to meet Alice, and he sees a deer leaping over bushes on the hillside.

Now, whenever I’ve come across deer in the wild, I am always awed; I think they’re beautiful, graceful, wildness incarnate. But some people see something else.

Pete, watching the deer, pats his pockets for a pen or pencil to jot down a note. But he hasn’t got a pencil. So here is the book’s last line: “He’d just have to remember, then, to put venison on the menu.”

6. Marie-Helene Bertino, author of 2 A.M. at the Cat’s Pajamas

6. Marie-Helene Bertino, author of 2 A.M. at the Cat’s Pajamas

I’m not one to approach the craft of writing with any sort of metaphysical bent. Those who speak of themselves as detached vessels through which prose flows can find me in the corner, rolling my damn eyes. However, there are a few aspects of the writing process I regard with a reverent wonder approaching the realm of soothsaying. None more so than last lines. I write the following with the typing equivalent of a straight face: before I know who the characters are, before I even know what the story is about, I hear its title and last line. I hear the last line, and then I write toward it. Not all the time, but usually.

This doesn’t mean I’m trapped. Knowing the airy location at which the story terminates does not mean I have any idea where the story will take me, or who I might invent as I journey. I don’t even know what the last line will mean to the characters. If an X marks the spot of where the story ends, the map still has no lines or countries, and the X could be a trap door leading to another dimension.

It’s really that simple.

Bring your sorry shit back tomorrow.

I vacillated between two possible last lines for my novel 2 A.M. at The Cat’s Pajamas. The difference between the two was the decision of who I wanted to end the story on — the young jazz singing protagonist, who we’ve struggled with for 280 pages, or a heretofore minor character. The former would leave the reader in an enclosed space, the room in which the little girl is rehearsing. The latter would end in an expansive place, literally and figuratively, leaving the door open for (what turned out to be) spirited interpretation. It would be impossible for me to convey the importance of the last line without you reading the novel, but I can say this: I knew the last word would be “tomorrow.” For a novel that takes place over the course of one day, that for the most part eschews flashbacks in order to keep all momentum pointed forward, it was important that the last word acknowledged the idea of a next day.

First lines are a challenge for me. They feel like work. If you want to know how to write a first line, I’d ask Kevin Wilson or Amy Hempel or Charles Baxter. If first lines belong to the story and its launch, last lines belong to the story’s effect. The last line launches the reader into what he or she will end up thinking about the story. Maybe that’s why they must feel delivered, and my job is to keep myself open in the way most conducive to hear them. I know, I know. Roll your eyes. I don’t blame you one bit.

I’d most likely never admit any of this had I never heard Amy Hempel say at a reading that she normally hears her last lines first, too. That, along with so many other things she has said about writing, validated the most internal of internal inclinations I’ve grown up feeling about the craft.

So if this all sounds like hooey to you, please take it up with her.

See Also: The Art of the Final Sentence

Image Credit: Geograph.