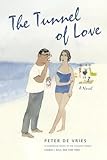

Imagine the irredeemably WASPish, cloistered Connecticut world of John Cheever if rendered by James Thurber, or John Updike’s suburban New England strivers and cheaters delivered by Oscar Wilde, or, better yet, imagine if you could make an alloy of H.L. Mencken’s irreligious perceptions and Dorothy Parker’s cagey sapience, and you might come close to beholding the vibrant abilities of Peter De Vries. Reared as a Calvinist in 1920s Chicago, De Vries was an editor at Poetry magazine, a staff writer at The New Yorker, and the author of some two dozen of the wittiest novels you’ll ever read, including the masterworks The Blood of the Lamb (1963) and Slouching Toward Kalamazoo (1983), as well as The Tunnel of Love (1954) and Rueben, Reuben (1964), just resurrected in handsome paperback by the University of Chicago Press.

Imagine the irredeemably WASPish, cloistered Connecticut world of John Cheever if rendered by James Thurber, or John Updike’s suburban New England strivers and cheaters delivered by Oscar Wilde, or, better yet, imagine if you could make an alloy of H.L. Mencken’s irreligious perceptions and Dorothy Parker’s cagey sapience, and you might come close to beholding the vibrant abilities of Peter De Vries. Reared as a Calvinist in 1920s Chicago, De Vries was an editor at Poetry magazine, a staff writer at The New Yorker, and the author of some two dozen of the wittiest novels you’ll ever read, including the masterworks The Blood of the Lamb (1963) and Slouching Toward Kalamazoo (1983), as well as The Tunnel of Love (1954) and Rueben, Reuben (1964), just resurrected in handsome paperback by the University of Chicago Press.

Contra the packaged laughs of a sitcom, all literary comedy is sedition, the much needed upsetting of expectation through the marshaling of wit. Wit is truth cleverly put — G.B. Shaw: “My way of joking is to tell the truth” — which, by the way, is why a bigot’s comedy can never be witty: racist jokes must court untrue convention while conforming to half-true cliché. One of the marks of any comedic savant remains that rare and precious thing: the cutting, memorable one-liner, and on this score De Vries never lets you down. From Comfort Me With Apples (1956): “There is nothing so monotonous as unrelieved novelty.” From The Glory of the Hummingbird (1974): “What is so quaint as yesterday’s wickedness?” From The Prick of Noon (1985): “The problem with treating people as equals is that the first thing you know they may be doing the same thing to you.” In The Tunnel of Love, especially, about the wedlocked hurly-burly of restive suburbanites, his Twainian one-liners come like a cataract: “Having a mind of one’s own doesn’t necessarily imply having any mind as such,” and “Experience is the shortest distance between anticipation and regret,” and “Curiosity could not resist what conscience must groan over.” His wit often pivots on the literary reference or allusion; in Sauce for the Goose (1981) he offers: “Frostbitten, Swinburnt, Wilde to Wilder.”

A goulash of one-liners does not a novel make, and part of De Vries’s vitalizing talent lies in his storytelling efficiency, his deft command of narrative form. Told, with Rashomon effect, from three wildly distinct points of view — a scheming chicken farmer, a Welsh rake who might be Dylan Thomas, and an incompetent British actor — Reuben, Reuben excavates the suburban eccentricities of 1950s Connecticut. De Vries is equally deft in the short-form: Without a Stitch in Time (1972) — also just reissued by the University of Chicago Press — compiles personal essays and stories in which the uninvited nostalgia of an ex-Calvinist finds itself defenseless against the cleverness of an assertive and secular humorist. Only those with a consummate lack of cleverness wield the word “clever” as an insult, and De Vries demonstrates just how much can be done with a creative intelligence charged by the clever and satirical and ironic. Let us now praise those saints at the University of Chicago Press who possess the smarts and good taste to return to print a peerless American maestro of wit.

A goulash of one-liners does not a novel make, and part of De Vries’s vitalizing talent lies in his storytelling efficiency, his deft command of narrative form. Told, with Rashomon effect, from three wildly distinct points of view — a scheming chicken farmer, a Welsh rake who might be Dylan Thomas, and an incompetent British actor — Reuben, Reuben excavates the suburban eccentricities of 1950s Connecticut. De Vries is equally deft in the short-form: Without a Stitch in Time (1972) — also just reissued by the University of Chicago Press — compiles personal essays and stories in which the uninvited nostalgia of an ex-Calvinist finds itself defenseless against the cleverness of an assertive and secular humorist. Only those with a consummate lack of cleverness wield the word “clever” as an insult, and De Vries demonstrates just how much can be done with a creative intelligence charged by the clever and satirical and ironic. Let us now praise those saints at the University of Chicago Press who possess the smarts and good taste to return to print a peerless American maestro of wit.

More from A Year in Reading 2014

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions’ Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions’ Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.