1.

The NBC Wednesday night lineup ad shows Debra Messing Mariska Hargitay, and Sophia Bush, side by side, sultry-eyed and pointing guns at the camera. Lady cops, badasses all, and with great hair.

There’s been much ado lately about powerful women on TV. Between Shonda Rimes’s Olivia Pope and her newest creation, defense lawyer Annalise Keating — both described as “authority figures with sharp minds and potent libidos” — along with Homeland’s Carrie Matheson, Mad Men’s Peggy Olsen, and The Good Wife’s Alicia Florrick, a golden age of women protagonists seems to be upon us. Or is it?

I’m a little concerned, frankly. True, we’re seeing a lot of women characters in high-powered jobs. And a decided feature in the current formula is that they are all extremely good at their jobs. But TV writers and showrunners also seem to be acting out the debate — launched full-force in 2012 with Anne Marie Slaughter’s piece in The Atlantic, “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” — around women, work, and family. When I look at these so-called powerful women on TV, I see a kind of Rorschach for audiences around two questions: Is this a woman whose life you’d actually want? And: Is this a woman whose life reflects any reality you know?

2.

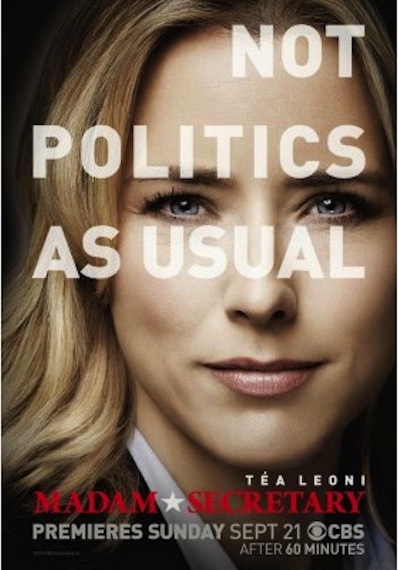

I had high hopes for Madam Secretary that the writing would be smart, the show would take on complex issues of the day, and that, yes, the portrayal of a woman in high office would be engaging. Téa Leoni is terrific and winning in the role of Secretary of State Elizabeth “Bess” McCord; on this most reviewers agree (not to mention the crack ensemble cast). She’s simultaneously intense and calm, assertive and disarming, sarcastic and sincere. You trust her, and you want her to succeed. She’s sexy in a sloppy, earthy sort of way, isn’t above or below using her feminine charms strategically; and in this particular way, she is nowhere near a Hilary Clinton knock-off: she is a different girlish-boyish animal altogether, of a younger generation who didn’t have to “act like a man, dress like a man” quite so strictly in order to rise and succeed. Like Alicia Florrick, she has natural instincts for the soft power/hard power one-two punch. She’s also, unlike Hilary (public Hilary, anyway), quite funny.

But in the first two episodes, I’ve had the woeful “Oh, please” reaction to a few of the show’s story elements, all of which have to do with the “having it all” trope. Bess’s husband Henry (Tim Daly) is hunky, brainy, solicitous, maternal, and utterly content (and of course he’s never had as much as a dalliance with a short-skirted co-ed). Bess initiates hand-wringing bedtime talk about not having as much sex as they used to; he assures her, silly girl, that it’s all fine. When their eldest daughter quits college because she can’t handle being the daughter of a public figure, Bess says to her go-between husband, “I just wish she had come to me.”

Ick! Argh! Oh, please! She is the Secretary of State: please tell me that a woman with such grave and innumerable daily responsibilities for ensuring peace and human rights around the globe isn’t whining about “only” having once-a-week-sex with her absurdly perfect husband and the fact that she can’t be available, in the midst of a Benghazi-like debacle, to hear her spoiled daughter (“I have to get a job? But I was going to finish my novel!”) complain about her mother being too famous and her father being too supportive.

Those portrayals of Secretary McCord’s personal life are unworthy of her; the writers are not doing Bess, or Leoni, justice. Creator Barbara Hall told Politico that a driving question behind the creation of the character was, “How do you deal with the president of the United States in the morning and the president of the PTA in the evening?” Herein lies the folly.

The idea that leaders at the highest levels — that anyone who’s chosen a profession requiring commitment beyond the pale, necessarily and rightly so — can be a “normal” parent, is goofy. The disconnect is between the writers and their own character: I don’t see Bess McCord entertaining such notions or expectations. She’s a realist, and a grownup, and can tell the difference between what matters and what doesn’t. I see her recognizing priorities in any given moment, having sex when she wants it and not worrying when she doesn’t, entreating her children to rise to the challenge — to neither be, nor expect to be, like everyone else.

3.

It seems to me that Barbara Hall, and the proponents of the “have it all” camp, are perpetrating something analogous to what Naomi Wolf did with her book Vagina — wherein she claims that women are not truly happy or whole if they are not having regular orgasms of the highest order. In response to the book, The New Yorker’s Judith Thurman said, brilliantly and hilariously:

It seems to me that Barbara Hall, and the proponents of the “have it all” camp, are perpetrating something analogous to what Naomi Wolf did with her book Vagina — wherein she claims that women are not truly happy or whole if they are not having regular orgasms of the highest order. In response to the book, The New Yorker’s Judith Thurman said, brilliantly and hilariously:

I would like to take issue with the idea that we should all have a happy vagina…It’s nice to have a happy vagina, I would hope everybody could have a happy vagina, but there are many times in a woman’s life where hey, she doesn’t have a happy vagina. And if you make her think that this is the goal, that she should be devoting her energies instead of to getting her PhD, or getting a better job or taking care of whatever it is… she needs to have a happy vagina. She may not be able to have a happy vagina. There are all kinds of people who are not in line immediately for a happy vagina.

If Bess McCord does not have a hunky, happy husband, and if she is not attentive to/worried about frequency of sex, and if she is not skipping out of meetings in which terrorist attacks are being prevented in order to listen to her children talk about their day…then surely she is not truly fulfilled, nor doing her job(s) well. If the PTA is not as important to her as POTUS or ISIS, then she is not a model powerful woman.

Me, I want my Secretary of State to be clear that, for as long as her job description includes tending to ISIS, then tending to ISIS is more important than the PTA.

4.

Inherent in Thurman’s response is a worldview I happen to share: energies must be devoted selectively. We are only human, and there is only so much energy and so much devotion. Devotion, by its nature, has obsessive, singularly focused qualities. Multiple devotions compete. The idea that such competition can be eradicated from human experience — in real life, or on TV — strikes me as misguided, a YA version of adult life. There is a cost to excellence; else it be other than excellence. I’ll say something surely controversial: I think one can do right by one’s family and be exceptionally accomplished in high leadership, or art, or service; but I don’t think one can be truly great at both. I think we’d all be a bit more relaxed if we accepted, and stopped judging, this truth.

Instead, Hall considers portrayals of more troubled figures — characters whose professional devotion creates friction and/or specific sacrifices in their personal lives — as “dark,” and has veered away from that toward, in her words, something more “entertaining,” and idealistic. These darker characters include compelling, if not always likable, characters like Claire Underwood from House of Cards, who decides not to have children because of her husband’s ambitions and their shared appetite for power; as well as Carrie Matheson, who deals with mental illness, alcoholism, sex-as-self-medication, and a disconnect with the idea of a “balanced life.” Perhaps also Peggy Olsen, who continually excels professionally while her love life fails and her family disapproves. I think of Sarah Linden from The Killing, who is obsessed with finding Rosie Larsen’s murderer, at the expense of devoted attention to her own son, and I think of Kima Greggs from The Wire, who’s much more interested in serous police work than the baby her partner has just given birth to. Even elegant Alicia Florrick has made choices: her kids and her career, but no happy vagina for her. I think, finally, of Leo McGarry, Chief of Staff on The West Wing, who — in response to his wife’s desperate plea, “It’s not more important than your marriage!” — declares, full-throated, Yes, yes it is: right now, while I’m doing it, it’s more important than my marriage.

I think also of more farcical portrayals of powerful, talented women — Selina Meyer in Veep and Laura Diamond in The Mysteries of Laura, who could give a shit about being perfect wives or mothers. It’s not that they don’t give a shit at all, but throwing off the perfectionism is what strikes me as a refreshing and more truthful brand of new feminism. Jill Lepore said it best:

I think that’s so complicated for women…but I think it’s actually been a really pernicious part of the current climate of political consultancy. Political consultants are clearly advising women candidates left and right: Tell the story of how you took very good care of your children. You must tell that story, again and again and again. I think it’s really dangerous. I think it really diminishes and impoverishes the range of experiences that people running for office can have…It has a kind of traplike quality for women politicians that all smart women politicians are quite aware of, and I think it’s important to think about the consequences of it.

We’re in an age of very good TV. Even network shows, I think, have leeway to be entertaining and complex and illuminating. Yes, yes it is: right now, what I’m doing is more important than a corny, conventional version of family happiness. Tell the truth, Madam Secretary; tell it slant if you have to, and with a sly wisdom, since you’ve shown in every other context so far that that’s your talent. If your husband bristles, if your kids get pissed, then let’s see how you handle that. How about, A great mom is sometimes not around, her vagina goes off duty, and she’s doing really important stuff. How about a new model, instead of a precious, poll-tested one.

So, my Rorschach response: Bess McCord, in her current incarnation, is not living the life that I would want, because it reflects fantasy archteype more than reality. There is nothing real or true, or even interesting, about being Great at Everything, and that imposition both flattens and disempowers an otherwise appealing character. I’m all for a golden age; I’m not sure we’re there yet.