History is written by the victors, Winston Churchill famously said. Fortunately for readers, story does not obey the same constraints. Fiction lets us explore many different perspectives, including that of the vanquished, the heterodox, the peculiar, or the deviant. Historical novels, in particular, allow us to relive the past without the neatness of history, and with all the complexity of the present. But how do novelists take history and turn it into story? What choices do they face in trying to transform real people into people of paper? In addition to creating complex characters, choosing an original and convincing point of view, and building a good plot, historical novelists must also transport us into another era, with its specific social norms, its cultural mood, and, above all, its idiosyncratic language. Here are three novels that successfully transform fact into fiction.

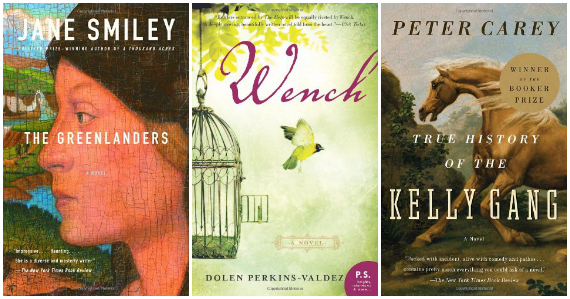

The Greenlanders by Jane Smiley

In the early fourteenth century, Asgeir Gunnarson set up a homestead in Greenland’s Eastern Settlement. With its mountains, fjords, and forests, the landscape is beautiful, but the winters are long and harsh. Still, Asgeir not only survives, but manages to leave a thriving farm to his children: his son Gunnar, who is a good if not a very bright worker, and his daughter, Margret, a skilled weaver whose independence of heart costs her dearly. As time passes, however, the land grows increasingly inhospitable, and the family faces challenges both physical and spiritual. This is an utterly engrossing book, which rings with authenticity both in its intimate details and in its larger implications. It is told in the distinctive voice of a Norse storyteller, yet without archaic dialogue or antiquated turns of phrases. And it gives a humane perspective on an otherwise brutal medieval saga. With The Greenlanders, Jane Smiley has given us a saga in the true sense of the word.

In the early fourteenth century, Asgeir Gunnarson set up a homestead in Greenland’s Eastern Settlement. With its mountains, fjords, and forests, the landscape is beautiful, but the winters are long and harsh. Still, Asgeir not only survives, but manages to leave a thriving farm to his children: his son Gunnar, who is a good if not a very bright worker, and his daughter, Margret, a skilled weaver whose independence of heart costs her dearly. As time passes, however, the land grows increasingly inhospitable, and the family faces challenges both physical and spiritual. This is an utterly engrossing book, which rings with authenticity both in its intimate details and in its larger implications. It is told in the distinctive voice of a Norse storyteller, yet without archaic dialogue or antiquated turns of phrases. And it gives a humane perspective on an otherwise brutal medieval saga. With The Greenlanders, Jane Smiley has given us a saga in the true sense of the word.

Wench by Dolen Perkins-Valdez

This beautiful novel follows the lives of four slave women who accompany their masters to Tawawa, a summer resort in Ohio. Each of the women—Lizzy, Reenie, Sweet, and Mawu—comes from a different plantation in the south; each has a unique relationship with her master, who is also her lover; each faces the temptation to run away to the uncertainty of freedom or hold on to her favored status back home. Wench is a novel about love, choice, and the illusions of both. It delves into the taboo subject of romantic and sexual relationships between slaves and slave-owners. When one sexual partner is a master and the other is a slave, is it ever possible to speak of love? When a woman must make a choice between freedom and her children, is it really a choice? Dolen Perkins-Valdez writes about these difficult ambiguities with clarity and compassion.

This beautiful novel follows the lives of four slave women who accompany their masters to Tawawa, a summer resort in Ohio. Each of the women—Lizzy, Reenie, Sweet, and Mawu—comes from a different plantation in the south; each has a unique relationship with her master, who is also her lover; each faces the temptation to run away to the uncertainty of freedom or hold on to her favored status back home. Wench is a novel about love, choice, and the illusions of both. It delves into the taboo subject of romantic and sexual relationships between slaves and slave-owners. When one sexual partner is a master and the other is a slave, is it ever possible to speak of love? When a woman must make a choice between freedom and her children, is it really a choice? Dolen Perkins-Valdez writes about these difficult ambiguities with clarity and compassion.

True History of the Kelly Gang by Peter Carey

Ned Kelly remains a popular hero in Australia, in spite of the fact that he was a horse thief, a bank robber, and a murderer. Peter Carey’s fictionalized relation of his life provides a compelling explanation for this apparent mystery. We meet the outlaw when he is a wee boy, struggling to survive on a “selection” (or a homestead). Ned’s father is transported to Van Diemen’s Land to serve out a jail sentence; his mother takes up with a series of suspicious men; and Ned and his siblings have nothing to eat but “the adjectival possums.” Ned grows up to be a keen observer of Australian society, and especially tuned to its many injustices. In letters he writes to his daughter, he describes the circumstances that led him to become an outlaw and makes a strong case for his actions. His writing lacks punctuation and contains grammatical errors that testify to his limited schooling, but he makes up for it with his poetic voice and his humor. An adjectival masterpiece, which calls into question the very existence of a “true history.”

Ned Kelly remains a popular hero in Australia, in spite of the fact that he was a horse thief, a bank robber, and a murderer. Peter Carey’s fictionalized relation of his life provides a compelling explanation for this apparent mystery. We meet the outlaw when he is a wee boy, struggling to survive on a “selection” (or a homestead). Ned’s father is transported to Van Diemen’s Land to serve out a jail sentence; his mother takes up with a series of suspicious men; and Ned and his siblings have nothing to eat but “the adjectival possums.” Ned grows up to be a keen observer of Australian society, and especially tuned to its many injustices. In letters he writes to his daughter, he describes the circumstances that led him to become an outlaw and makes a strong case for his actions. His writing lacks punctuation and contains grammatical errors that testify to his limited schooling, but he makes up for it with his poetic voice and his humor. An adjectival masterpiece, which calls into question the very existence of a “true history.”

These three novels reshape fact into fiction and, in the process, they teach us not just what happened in another era, but how what happened in another era changed one character’s life.