A few weeks ago I was at WBEZ here in Chicago to record an interview with an NPR reporter who was in Vermont. The sound engineer asked me to start talking so she could test my microphone levels. “Four score and seven years ago,” I began, “our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation.” Right about when I got to “It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here,” she stopped me and said “Ok, we’re good to go. But….was that the Gettysburg Address?”

Yes, I have the Gettysburg Address memorized. I have for about two years, since I recited it at my 30th birthday party, in the normal fashion. I also have a framed picture of Lincoln above my desk, a set of 10 presidential Pez dispensers (mint condition! new in box!), both a William Henry and Benjamin Harrison figurine, many presidential mugs, magnets, and t-shirts, and a bottle of “General’s Reserve” wine from Galena, Illinois. These are the things that collect in one’s life when one is a presidential history buff. (Actually, everything listed above was a gift. Having a singular hobby also makes one really easy to shop for.)

Yes, I have the Gettysburg Address memorized. I have for about two years, since I recited it at my 30th birthday party, in the normal fashion. I also have a framed picture of Lincoln above my desk, a set of 10 presidential Pez dispensers (mint condition! new in box!), both a William Henry and Benjamin Harrison figurine, many presidential mugs, magnets, and t-shirts, and a bottle of “General’s Reserve” wine from Galena, Illinois. These are the things that collect in one’s life when one is a presidential history buff. (Actually, everything listed above was a gift. Having a singular hobby also makes one really easy to shop for.)

Five years ago I set out to read a biography of every American president in chronological order (a project I chronicle at my blog At Times Dull). When I wrote about the project here at The Millions three and a half years ago, I was one-third of the way through, and having just seen William H. Taft off to the big bathtub in the sky, I’m now roughly two-thirds through.

For my own reference (and amusement, as the jollies are few and far between for a presidential biography blogger) I’ve grouped the presidents into eras as I go: The Founding Fathers, The Nation Builders, The Expansionists, The Compromisers, The Civil War Presidents, and The Beards. At last writing I had just reached Abraham Lincoln after a long string of Compromisers — the unhappy and mostly forgotten presidents who had to wade through the political morass of antebellum America. I have once again arrived at presidential legend, this time Teddy Roosevelt, after a long string of forgotten ones, this time the Beards.

The Beards are Hayes, Garfield, Arthur, Cleveland, Harrison, and McKinley, and I have a specific fondness for them, as I have a specific fondness for the presidents of each era. Situated between Grant and Roosevelt, they oversaw the 40 years that pulled the nation from Reconstruction into the Gilded Age. It wasn’t pretty. While the government had been focused on the Civil War and Reconstruction, the civil service had become horribly corrupt, interstate commerce increasingly dominated a country that was designed for intrastate commerce, and the rise of corporations meant the corollary rise of organized labor, but domestic legislation hadn’t caught up with any of it.

This era needed a new kind of leadership. It felt strange to me to go from the Civil “we-always-knew-this-was-coming” War to an era the Founding Fathers literally could not have imagined. One of my favorite presidential anecdotes took place during South Carolina’s Nullification Crisis of 1832, when a question of whether something was Constitutional led someone to just go ask 81-year-old James Madison. He was like “no” and that kind of settled it. Not only did The Beards not have the author of the Constitution around as their phone-a-friend, the Constitution itself had less and less to say about the practical reality of their time. The Beards are the unsung heroes who oversaw that transition and started laying the framework of modern America.

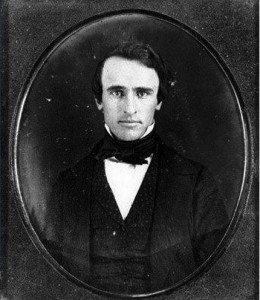

And when I say it wasn’t pretty, I don’t mean visually, because ladies and gentleman, Rutherford B. Hayes was shockingly good-looking. Look at that guy! Why don’t they teach this in school? That he grew a beard before his presidency is a national tragedy. Rud Hayes is one of my favorite presidents, and not just because I can get lost for days in his eyes. He took office after Grant, and while I love Ulysses S. Grant, he wasn’t a good president.

Grant too frequently followed the advice of New York political boss Roscoe Conkling, who was a true villain. He came from a long line of New York political bosses — Martin Van Buren, Thurlow Weed, William Seward — who had enormous influence in the federal government. It was customary for the president to have a wary but necessary relationship with these slimeballs (the lifelong rivalry between Thurlow Weed and Millard Fillmore is pretty juicy, if you have the time). It all came down to civil service jobs. At the time, the president personally appointed every upper-level federal job in the nation. This might have been wise in 1790, but it made no sense, in 1876, for a president who was born and raised in Ohio to appoint the postmaster of Tulsa.

But it was great if you lived in Tulsa, because then you could do a little campaigning for Rud Hayes — hand out some pamphlets or give a speech, maybe — and then when he became president write him a letter and say “I have a brother-in-law who would make a great postmaster.” This practice was called patronage, and as stupid as it was it was the only way to get elected, so everybody did it.

The best civil service jobs were in New York, namely at the New York Customs House. From what I understand, if you worked at the Customs House you could just show up now and then, collect a bag of money, and leave without doing any work. If you were running for president and you wanted New York’s electoral votes, which you did, you had to ask for Roscoe Conkling’s help. He would get you elected and then he got to dictate who got all the New York jobs.

Rud Hayes wanted civil service reform, but nobody believed it was possible to dismantle a system with such a tight hold on electoral politics. It’s analogous to campaign finance reform today — nobody’s against it, nobody’s going to do it. But Handsome Rud up there was determined, and to prove it he up and fired the man in the most coveted, most notoriously corrupt civil service job — New York customs collector Chester A. Arthur.

Rud didn’t run for a second term. He knew that his reforms had burned too many political bridges for him to stand a chance at re-election, so he fell on his reform sword and bowed out. (He actually hadn’t won the election that made him president in the first place, but that’s another story.) When it came time for the Republicans to choose a candidate to succeed him, they had a problem. Rud’s firing of Arthur had split the party in two. On one side were the Stalwarts, led by Conkling, who wanted to centralize power and continue being corrupt buttheads, and on the other side were the Radicals, who thought the party should stop coasting on Lincoln’s reputation and start enacting social change. Neither faction was large enough to push their own candidate through, and as much as the Radicals disliked Conkling’s political machine, they needed his influence. Roscoe Conkling was still hopping mad about Rud firing Arthur, and they couldn’t afford to alienate him any further.

As a compromise, they suggested unknown Ohio senator James Garfield as the presidential candidate (“Who’s that? Well, whatever,” everyone said), and let Conkling hand-pick the vice presidential candidate. Conkling, in a fit of dramatic revenge, chose Chester Arthur.

Thus giving us President James Garfield, and upon his death President Chester Arthur. When Garfield lay dying, one newspaper editor ruminated on the fact that an infamously corrupt administrator who had never held elected office and was given his current office as a show of spite was one infected gunshot wound away from the highest office in the land, and concluded: “Chet Arthur as president! Good God!”

Indeed. And yet Arthur’s one term presidency wasn’t full of the monkey business everyone expected. Potentially abashed by the dire predictions for his administration, he did his best to simply carry out the party platform without injecting his own ideas. He distanced himself from Conkling, and even supported civil service reform measures, to every ironist’s great delight. At President Grant’s funeral, he found himself sharing a carriage with President Hayes, the man who, by publicly firing him, had given him a political career he never wanted. By all accounts they were perfect gentlemen.

This period was full of presidents who seemed to rise to that position by accident. Hayes hadn’t won his election. Garfield was a compromise candidate. Arthur wasn’t even a politician (and he was probably born in Canada). Cleveland, Harrison, and McKinley were all elevated on the merits of their work ethic. The parties favored diligence over vision, a trend that continued until McKinley’s death gave us President Roosevelt and a new mold of president as political celebrity.

But if At Times Dull has taught me anything, it’s that America gets a few great presidents and can survive a lot of mediocre ones, and after 225 years we still can’t predict which will be which. Most presidents do more reacting than acting, and to be a great president you have to react to something momentous. The Beards brought a lot of their own drama to the White House (Garfield had chronic diarrhea, Arthur and Cleveland both had secret medical problems), but the national issues they faced are ones we’ve stopped talking about. At least in the case of Arthur — who just wanted to complete the task entrusted to him without confirming everyone’s doubts — I actually don’t think he’d mind.

The Presidential Biographies I’ve Read (Since Last Time)

- Lincoln by David Herbert Donald

- Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy by David O. Stewart

- Grant by Jean Edward Smith

- Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior and President by Ari Hoogenboom

- The Garfield Orbit by Margaret Leech

- Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Alan Arthur by Thomas Reeves

- An Honest President: The Life and Presidencies of Grover Cleveland by H. Paul Jeffers

- Benjamin Harrison: Hoosier Statesman by Harry J. Sievers

- In the Days of McKinley by Margaret Leech

- The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt & Theodore Rex by Edmund Morris

- William Howard Taft by Henry F. Pringle