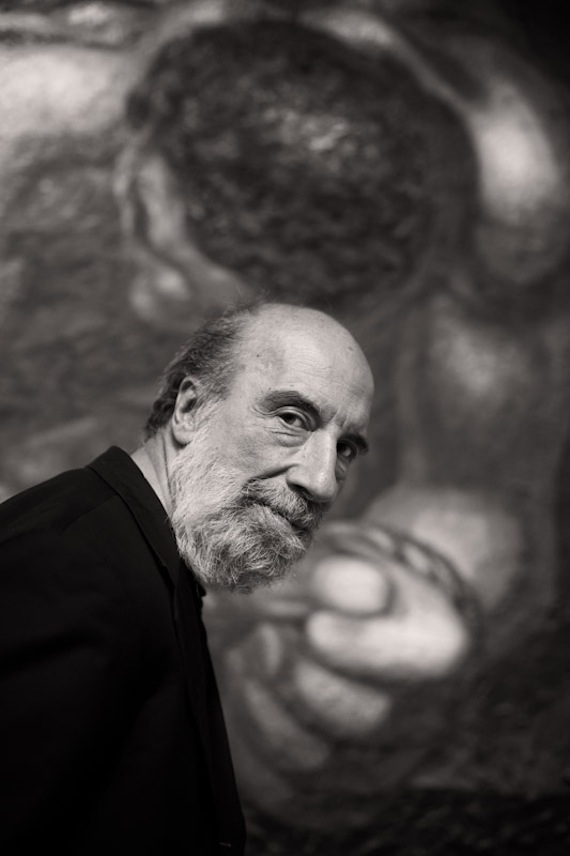

Raúl Zurita, born in Santiago in 1950, has published more than 20 books of poetry and received countless honors and prizes including Chile’s National Literature Prize in 2000. When he was two years old, his father died, leaving him and his infant sister in the care of their mother and maternal grandparents, who immigrated to Chile from Italy. The morning of Zurita’s father’s funeral, his grandfather died of a heart attack. His mother worked long days as a secretary while his grandmother looked after him and his sister. She spoke to her grandchildren about Genova and the Rapallo Sea, the Italian painters and musicians she admired, and, most of all, The Divine Comedy. In a recent interview in Uruguay’s El País with Ilan Stavans, Zurita says, “Instead of stories, [our grandmother] told us passages from the Inferno, which both terrorized and fascinated us.”

Zurita’s first book of poems Purgatorio was published in 1979 during the early years of the Pinochet dictatorship. An engineering student at the University of Federico Santa María in Valparaíso when the coup took place in 1973, Zurita was arrested, detained, and tortured. He spent six weeks incarcerated aboard a military ship holding 800 prisoners cramped into a space with the capacity for 100. As told to Daniel Borzutzky in a 2009 Poetry Foundation interview, Zurita was carrying a file, the poems that would become the book Purgatorio, when he was arrested the morning of September 11, 1973, and the arresting officers suspected his papers might include coded messages. The senior military officer who made the final decision about Zurita’s potentially subversive writings threw the poems into the sea. The book begins with these lines:

my friends think

I’m a sick woman

because I burned my cheek

And a few pages later:

My name is Rachel

I’ve been in the same

business for many

years. I’m in the

middle of my life.

I lost my way.–

(translated by Anna Deeny)

Jeremy Jacobson’s 1985 translation of Purgatorio, published by the Latin American Literary Review Press, introduced Zurita to English language readers as “the most important young poet writing in Chile today,” and included an essay by Scott Jackson on “the union of mathematics and poetry” in Zurita’s work. The University of California Press issued a fantastic new translation of Purgatorio in 2009, at the hands of the poet and Latin American literature scholar Anna Deeny. C.D. Wright gives the following assessment in the new translation’s foreword: “with a mysterious admixture of logic and logos, Christian symbols, brain scans, graphics, and a medical report, Zurita expanded the formal repertoire of his language, of poetic materials, pushing back against the ugly vapidity of rule by force.”

Jeremy Jacobson’s 1985 translation of Purgatorio, published by the Latin American Literary Review Press, introduced Zurita to English language readers as “the most important young poet writing in Chile today,” and included an essay by Scott Jackson on “the union of mathematics and poetry” in Zurita’s work. The University of California Press issued a fantastic new translation of Purgatorio in 2009, at the hands of the poet and Latin American literature scholar Anna Deeny. C.D. Wright gives the following assessment in the new translation’s foreword: “with a mysterious admixture of logic and logos, Christian symbols, brain scans, graphics, and a medical report, Zurita expanded the formal repertoire of his language, of poetic materials, pushing back against the ugly vapidity of rule by force.”

Purgatorio is the first in a three-book sequence, including Anteparaíso (1982), and La Vida Nueva (1994), where post-1973 Chile appears in a Dante-esque frame. Zurita’s oeuvre extends beyond the page through his interventions in physical landscapes: the poet documents the burning of his own face in Purgatorio, Anteparaíso includes photographs of 15 lines of poetry written across the New York City skyline in 1982, and La Vida Nueva features sky drawings enhanced with handwriting, as well as a photograph of the 3-kilometer-long phrase composed in the Atacama desert in 1993, which is only legible from the sky: “ni pena ni miedo” (neither pain nor fear).

Purgatorio is the first in a three-book sequence, including Anteparaíso (1982), and La Vida Nueva (1994), where post-1973 Chile appears in a Dante-esque frame. Zurita’s oeuvre extends beyond the page through his interventions in physical landscapes: the poet documents the burning of his own face in Purgatorio, Anteparaíso includes photographs of 15 lines of poetry written across the New York City skyline in 1982, and La Vida Nueva features sky drawings enhanced with handwriting, as well as a photograph of the 3-kilometer-long phrase composed in the Atacama desert in 1993, which is only legible from the sky: “ni pena ni miedo” (neither pain nor fear).

Once the millennium turned, Zurita published Poemas Militantes (2000), INRI (2003), Los Países Muertos (2006), and In Memoriam (2007), among others. Zurita (2011), an almost 750-page volume, unfolds from the evening of September 10 to the morning of September 11, 1973, and includes excerpts from the poet’s other books, for example: three pages of the electroencephalogram (EEG) embedded with text that closes Purgatorio, a few photographs of the New York City skywriting that appeared in Anteparaíso, and a middle section (starting on page 358 of Zurita) from his 1985 book Canto a Su Amor Desaparecido, translated in 2010 by Daniel Borzutzky as Song for His Disappeared Love. Zurita holds space, represented by the blocks of text arranged like the niches in a columbarium wall, for the disappeared during Chile’s Pinochet regime, as well as those lost during political upheaval in other countries and regions including Argentina, the Amazon, Haiti, Nicaragua, the United States, Cuba, and El Salvador. The first of the United States-related blocks of text reads as follows:

Once the millennium turned, Zurita published Poemas Militantes (2000), INRI (2003), Los Países Muertos (2006), and In Memoriam (2007), among others. Zurita (2011), an almost 750-page volume, unfolds from the evening of September 10 to the morning of September 11, 1973, and includes excerpts from the poet’s other books, for example: three pages of the electroencephalogram (EEG) embedded with text that closes Purgatorio, a few photographs of the New York City skywriting that appeared in Anteparaíso, and a middle section (starting on page 358 of Zurita) from his 1985 book Canto a Su Amor Desaparecido, translated in 2010 by Daniel Borzutzky as Song for His Disappeared Love. Zurita holds space, represented by the blocks of text arranged like the niches in a columbarium wall, for the disappeared during Chile’s Pinochet regime, as well as those lost during political upheaval in other countries and regions including Argentina, the Amazon, Haiti, Nicaragua, the United States, Cuba, and El Salvador. The first of the United States-related blocks of text reads as follows:

USA Niche. Found in Barracks 12. Northern countries and

dispatched to eat themselves up thanks to their dreams

of special shields, of murderers of blacks, of domina-

tion. They descended the sky and they called Hiroshi-

ma the country that blazed; Central countries, valleys

and Chilean gluttons. The graves are nights and every-

thing is night in the American grave. They rest in peace like

the bison. It was a Navajo phrase. As it was written, Amen.

(translated by Daniel Borzutzky)

Zurita is a rewriting, an epic translation, of the poet’s complete oeuvre. The book includes a handful of excerpts from previously published work alongside the new poems, all echoing each other. The disappeared and missing people of Chile and the Americas are at the core of Zurita, and the surrounding sequences reveal the searching and dreams of those reflecting on humanity’s failures all over the world, including Thomas Mann, Kurosawa, and Pink Floyd. Zurita’s mandate is that we must keep saying it (writing it, publishing it, reading it), over and over, so that we do not forget the horror of the past. Our past is with us in the present, and we will carry it forward, either as memory or repetition.

The closing pages of Zurita include a sequence of photographs from his latest project involving an intervention in the physical landscape, titled “Your Life Breaking.” The photographs of the sea cliffs in northern Chile have phrases typed out across them to show the kind of poetry installation Zurita would like to achieve there. The phrases, which correspond to the subsections in the table of contents of Zurita, include: “You Will See Soldiers at Dawn,” “You Will See the Snows of the End,” “You Will See Cities of Water,” “You Will See What Goes,” “You Will See Not Seeing,” and “And You Will Weep.” The final lines of the book are a short poem titled “Sky Below:”

The sun is rising and I am leaving, papá. Deep

is the well of time. The mountains remain

covered and perhaps it will rain at last. Can you imagine

the breakers crashing again on

these stones, papá? You never tell me anything, papá.

(translated by Magdalena Edwards)

At the moment, Zurita says he has nothing left to say or write by way of poetry. He is steadily at work on a translation of Dante’s Inferno, and he has decided to preserve the terza rima form in Spanish, which makes the project slow going. The first stanza goes (gorgeously) like this: “A mitad del camino de esta vida, / me encontraba en una selva oscura / pues la recta vía estaba perdida.” Zurita also recently translated Hamlet into Spanish for a stage production under the direction of Gustavo Meza that was such a hit in Santiago when it debuted in late 2012, a second production went up in mid-2013. He explained to me by email that while he is not writing original poems, “translation frees me from anguish.”

Zurita has two fascinating new books out this year, both collaborations with fellow poets, one a bilingual selection of poems from Latin America, and the other a conversation about death and life.

Pinholes in the Night: Essential Poems from Latin America (Copper Canyon Press 2014), with Forrest Gander at the helm as editor, is a bilingual selection of 18 20th-century Spanish-language poems. The volume takes its title from Alejandra Pizarnik’s “Diana’s Tree:” “a pinhole in the night / invaded suddenly by an angel.” The 15-century Nahuatl poem “Nezahualcóyotl” opens the collection, a choice that highlights the problematic nature of Spanish as one of the imposed languages of Latin America, as Zurita explains in his introduction. What moves me most about Pinholes — more than the wonderful translation choices by Gander, including California poet Jen Hofer for Nicanor Parra’s “Soliloquy of the Individual” and Ernesto Cardenal’s “Prayer for Marilyn Monroe,” and Anna Deeny for Idea Vilariño’s “Not Anymore,” and more than Zurita’s exhilarating introduction, “written in a fever-dream between serious surgeries,” where he debates the impossible choice of one poem each by Mistral, Vallejo, and Neruda, notes which poems he would have chosen from the Portuguese (no doubt Ferreira Gullar’s “Poema Sujo”), and discusses why he includes Juan Rulfo’s short story “You Don’t Hear Dogs Barking” — is that the book is precisely not a poetry anthology. Pinholes in the Night is not exhaustively encyclopedic, but rather deeply personal and thus imperfectly brilliant, a light that helps us understand Zurita and his worldview, the lyrical landscape he treads, a little better.

Pinholes in the Night: Essential Poems from Latin America (Copper Canyon Press 2014), with Forrest Gander at the helm as editor, is a bilingual selection of 18 20th-century Spanish-language poems. The volume takes its title from Alejandra Pizarnik’s “Diana’s Tree:” “a pinhole in the night / invaded suddenly by an angel.” The 15-century Nahuatl poem “Nezahualcóyotl” opens the collection, a choice that highlights the problematic nature of Spanish as one of the imposed languages of Latin America, as Zurita explains in his introduction. What moves me most about Pinholes — more than the wonderful translation choices by Gander, including California poet Jen Hofer for Nicanor Parra’s “Soliloquy of the Individual” and Ernesto Cardenal’s “Prayer for Marilyn Monroe,” and Anna Deeny for Idea Vilariño’s “Not Anymore,” and more than Zurita’s exhilarating introduction, “written in a fever-dream between serious surgeries,” where he debates the impossible choice of one poem each by Mistral, Vallejo, and Neruda, notes which poems he would have chosen from the Portuguese (no doubt Ferreira Gullar’s “Poema Sujo”), and discusses why he includes Juan Rulfo’s short story “You Don’t Hear Dogs Barking” — is that the book is precisely not a poetry anthology. Pinholes in the Night is not exhaustively encyclopedic, but rather deeply personal and thus imperfectly brilliant, a light that helps us understand Zurita and his worldview, the lyrical landscape he treads, a little better.

Saber Morir: Conversaciones (Universidad Diego Portales 2014) is a book-length conversation about knowing how to die and how to live undertaken by Raúl Zurita and Ilan Stavans, the Mexican poet and translator who edited The FSG Book of Twentieth-Century Latin American Poetry (FSG 2011) (it bears noting that the FSG Book, a representative anthology of Latin America poetry, attempts to do everything Pinholes in the Night does not attempt, and vice versa, such that Pinholes and The FSG Book are fruitful companions). Saber Morir, which has not been translated into English yet, is intimate and rambling and covers life experience, books, music, film, history, and philosophy. We learn that both Zurita and Stavans have trepidations about closing their eyes when they go to sleep at night, as well as feel terrorized by the possibility of dying in a hospital. Both men embrace getting older. Stavans says, “I like feeling older, being less afraid of life, not doubting the way I used to.” Zurita says, “there are only two states: or you are young or you are old.” He goes on to explain: “I feel potent in my pains, in my curved spine, in the increasing difficulty of holding the pages when I read in public.” Of his day-to-day life with Parkinson’s, he intimates: “I might have a bizarre sense of beauty, but my disease feels beautiful to me. It feels powerful.”

Saber Morir: Conversaciones (Universidad Diego Portales 2014) is a book-length conversation about knowing how to die and how to live undertaken by Raúl Zurita and Ilan Stavans, the Mexican poet and translator who edited The FSG Book of Twentieth-Century Latin American Poetry (FSG 2011) (it bears noting that the FSG Book, a representative anthology of Latin America poetry, attempts to do everything Pinholes in the Night does not attempt, and vice versa, such that Pinholes and The FSG Book are fruitful companions). Saber Morir, which has not been translated into English yet, is intimate and rambling and covers life experience, books, music, film, history, and philosophy. We learn that both Zurita and Stavans have trepidations about closing their eyes when they go to sleep at night, as well as feel terrorized by the possibility of dying in a hospital. Both men embrace getting older. Stavans says, “I like feeling older, being less afraid of life, not doubting the way I used to.” Zurita says, “there are only two states: or you are young or you are old.” He goes on to explain: “I feel potent in my pains, in my curved spine, in the increasing difficulty of holding the pages when I read in public.” Of his day-to-day life with Parkinson’s, he intimates: “I might have a bizarre sense of beauty, but my disease feels beautiful to me. It feels powerful.”