1.

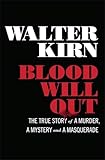

If you do a Google image search for “Walter Kirn” you will get a banner of options that you can use to further winnow your results: “Maggie McGuane,” “Clark Rockefeller,” “Amanda Fortini,” “Princeton.” Click on one, you get Walter Kirn the boyfriend. Click another, the ex-husband and father. There is his Ivy League iteration, his sucker iteration. This last one (sucker) could also be the writer iteration, or even, as Kirn himself suggests, the betrayer iteration. I rarely do such a thing — Google image search someone for a better understanding of them. But by the time I’d finished Kirn’s new book, Blood Will Out: The True Story of a Murder, a Mystery, and a Masquerade, I was left wondering less about Kirn’s subject, a homicidal shape shifter named Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter known in the book as Clark Rockefeller, than about Kirn himself. So I resorted to a last-ditch effort at trying to get a read on him — I looked for a photo. Predictably, instead of defining Kirn any better, the photos I found only sliced him up into different versions, all of which in the end looked blurry.

If you do a Google image search for “Walter Kirn” you will get a banner of options that you can use to further winnow your results: “Maggie McGuane,” “Clark Rockefeller,” “Amanda Fortini,” “Princeton.” Click on one, you get Walter Kirn the boyfriend. Click another, the ex-husband and father. There is his Ivy League iteration, his sucker iteration. This last one (sucker) could also be the writer iteration, or even, as Kirn himself suggests, the betrayer iteration. I rarely do such a thing — Google image search someone for a better understanding of them. But by the time I’d finished Kirn’s new book, Blood Will Out: The True Story of a Murder, a Mystery, and a Masquerade, I was left wondering less about Kirn’s subject, a homicidal shape shifter named Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter known in the book as Clark Rockefeller, than about Kirn himself. So I resorted to a last-ditch effort at trying to get a read on him — I looked for a photo. Predictably, instead of defining Kirn any better, the photos I found only sliced him up into different versions, all of which in the end looked blurry.

Kirn is most well known for his novels, two of which (Up In the Air and Thumbsucker) were made into feature films. Blood Will Out, as its title suggests, is not a novel. It is a “true story,” at least in a sense. Kirn admits his motivation in undertaking the favor that lead him to Clark early on, and it is not an altruistic one. He is a writer in search of material and Clark sounds promising. So he drives a severely disabled dog from his home in Livingston, Montana to a stranger (Clark) in Manhattan, all for the promise of a story. And the story-gods deliver. Clark is brimming with material. He is a wealthy, effete owner of rare modern art, an intense dog-lover convinced he can cure Shelby — the dog Kirn has delivered — of her crushed spine through homeopathic remedies and acupuncture. He is pathologically self-involved, giving lengthy monologues without ever stopping to thank, inquire about, or pay the man who has just delivered an incontinent high-maintenance creature to his doorstep. Nevertheless, and perhaps because of Kirn’s persistent desire for material, the two become friends of a sort. Clark’s end of the relationship is mostly composed of soliciting favors. Kirn is more generous, even if he does have an ulterior motive. He listens to Clark when he has family troubles, even visits him, skeptically intrigued by Clark’s offers to introduce him to J.D. Salinger (who, of course, never materializes). They fall in and out of touch until Clark abducts his own daughter in 2008 and after a brief pursuit is arrested. Once he’s in custody, it’s discovered that Clark Rockefeller is also Christopher Chichester, who is wanted for questioning in the murder of a man named John Sohus. Clark, it turns out, is a classic American shape shifter. “The villain with a thousand faces,” Kirn calls his type, “a kind of charming, dark-side cowboy, perennially slipping off into the sunset and reappearing at dawn in a new outfit.”

Kirn is most well known for his novels, two of which (Up In the Air and Thumbsucker) were made into feature films. Blood Will Out, as its title suggests, is not a novel. It is a “true story,” at least in a sense. Kirn admits his motivation in undertaking the favor that lead him to Clark early on, and it is not an altruistic one. He is a writer in search of material and Clark sounds promising. So he drives a severely disabled dog from his home in Livingston, Montana to a stranger (Clark) in Manhattan, all for the promise of a story. And the story-gods deliver. Clark is brimming with material. He is a wealthy, effete owner of rare modern art, an intense dog-lover convinced he can cure Shelby — the dog Kirn has delivered — of her crushed spine through homeopathic remedies and acupuncture. He is pathologically self-involved, giving lengthy monologues without ever stopping to thank, inquire about, or pay the man who has just delivered an incontinent high-maintenance creature to his doorstep. Nevertheless, and perhaps because of Kirn’s persistent desire for material, the two become friends of a sort. Clark’s end of the relationship is mostly composed of soliciting favors. Kirn is more generous, even if he does have an ulterior motive. He listens to Clark when he has family troubles, even visits him, skeptically intrigued by Clark’s offers to introduce him to J.D. Salinger (who, of course, never materializes). They fall in and out of touch until Clark abducts his own daughter in 2008 and after a brief pursuit is arrested. Once he’s in custody, it’s discovered that Clark Rockefeller is also Christopher Chichester, who is wanted for questioning in the murder of a man named John Sohus. Clark, it turns out, is a classic American shape shifter. “The villain with a thousand faces,” Kirn calls his type, “a kind of charming, dark-side cowboy, perennially slipping off into the sunset and reappearing at dawn in a new outfit.”

By the time Kirn wrote Blood, Gerhartsreiter had already been tried and convicted of murder. There had been other books written about him, and a TV movie made. As subject matter, he’d been strip-mined, picked apart in court and media alike. Even if you’ve never heard of Gerhartsreiter or any of his aliases, reading the book’s jacket copy or even just the title will clue you in to the fact that he’s a fraud. Thus the “mystery” of the book’s title isn’t really a forensic one. In part it’s centered on Kirn himself, who beats himself upside the head with the same questions throughout the book: how could he have been so duped, how dare someone so lavishly swindle him, and — perhaps the central question — is he, ultimately, victor or victim? While we know Kirn initially befriends Clark for material, it seems to be pride that drives him to continue to meet with Gerhartsreiter post-conviction. Even then, Gerhartsreiter never provides any answers, only a warped reflection of Kirn. When Kirn asks him, over prison phone, what the key to manipulating people is, Gerhartsreiter says, “I think you know.” Only when Kirn concedes this does Gerhartsreiter give him an answer: “Vanity, vanity, vanity.”

2.

In Genesis, when Rebekah is pregnant with twins, one of whom will steal the birthright and identity of the other, the Lord says to her: “Two nations are in your womb, and two peoples from within you will be separated; one people will be stronger than the other, and the older will serve the younger.”

I thought of this story — that of Jacob and Esau — while reading Blood Will Out. I thought of how perhaps both twins exist in each person, dueling and grabbing each other by the heels, vying for the birthright, stealing identity, deceiving. Jacob the original identity thief, Clark another incarnation. Kirn is in there, too, elbowing his way to the front.

According to Kirn’s blog, he’s been regularly reading and thinking about the Bible. He boils the story of Jacob and Esau, and indeed the whole Old Testament, down to property law. Blood carries this tradition: whose property is Gerhartsreiter’s story? In sections of the book, Kirn refers to Gerhartsreiter as an eater-of-souls, someone who, lacking innate creativity, believes he can, by murdering someone, subsume their talents. “Sorry, Clark,” Kirn writes halfway through the book, “You asked for it, old sport. You knew who I was, and deep down I knew who you were, even if I played dumb there for a time — so dumb that I didn’t realize I was playing, which, looking back, was a fairly cunning strategy. You were material. Surprise, surprise. Look in your wallet; it’s empty. Now look in mine.” Kirn’s won, he’s telling us, and his victory is tangible — we’re holding it in our hands. But I’m not sure it’s as Kirn presents it, not sure he was ever employing any strategy save that of general gatherer. It seems telling himself (and us) that he was in control the whole time is what he must do in order to survive. The alternative — that he was thoroughly and utterly manipulated and played, that it might just as easily have been him dismembered and buried in his own backyard — is too inconceivable.

Kirn writes about the Bible that, “once it unfolds some, it starts reading you.” I heard something similar once from an eccentric priest: as you get deeper into the Bible, you begin to recognize yourself in it. The exoduses and betrayals, the sacrifices and selfishness. This seems to be a kind of litmus test of good literature: can you locate yourself in it? Kirn seems to have located himself in Gerhartsreiter, who, if nothing else, occupies the role of mirror. In recounting his experience, he shows us not only how little we might know another person, but how little we might know ourselves.