1.

First, a brief background on the Song of Songs. I didn’t come across it till I was 26, when I received a copy of the Tanakh as a wedding gift. I read it on the plane en route to our honeymoon the morning after the wedding, trying not to dwell on the heavy-handedness of giving the Tanakh as a wedding gift when one half of the couple in question is Jewish and the other is not and neither are religious. Somewhere over the Atlantic I flipped ahead, tired and a little bored, until I came upon the Song of Songs and its beauty pierced my atheistic heart.

The Song of Songs is a love poem, mysterious and incandescent, wedged between the books of Job and Ruth. It’s a biblical oddity: alone among the books of the Tanakh, it makes no mention of God. It involves two lovers in exquisite harmony. They address one another, sing one another’s praises, long for one another when they’re apart. There’s an inexplicable sense of momentum about it; perhaps it’s not too much to suggest that it sings. It’s possible that you’ve seen quotes from it here and there, whether or not you’ve read the text. I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine: words written in calligraphy on countless Jewish marriage contracts. Later, a variation: I am my beloved’s and his desire is for me. Such themes and variations abound. If you have an interest in gorgeous and mysterious text, you might find it worth reading, whether or not you harbor any particular religious sentiment.

Whether or not the Song of Songs itself harbors any particular religious sentiment has been a matter of some debate. “If the Torah had not been given,” Rabbi Akiva said, in the second century A.D., “the Song of Songs would have sufficed to guide the world.” Akiva read the Song of Songs as allegory, the lovers standing in for Akiva’s god and Akiva’s god’s people. But the lovers in the Song are plainly lovers, and the obvious eroticism of several verses lends a certain awkwardness to allegorical interpretation. One modern — and by no means uncontested — interpretation is that the Song is a collection of wedding songs. The interpretation I like best is that it isn’t allegorical, that it is indeed a song of two lovers, but that because it is concerned with love it is holy. But whatever else the Song of Songs is, I find it to be a sublime piece of work.

“For it is not a melody that resounds abroad,” St. Bernard of Clairvaux wrote in the 12th century, in one of his 86 sermons on the Song of Songs, “but the very music of the heart, not a trilling on the lips but an inward pulsing of delight, a harmony not of voices but of wills.” He also viewed it as allegorical — hence the 86 sermons — but this still rings true to me, both regarding the Song of Songs specifically and as a description of the closed and private world of a romantic relationship, that discrete territory with its own language, customs, and history where one lives with one’s beloved: “It is a tune you will not hear in the streets,” he writes, “these notes do not sound where crowds assemble; only the singer hears it and the one to whom he sings—the lover and the beloved.”

2.

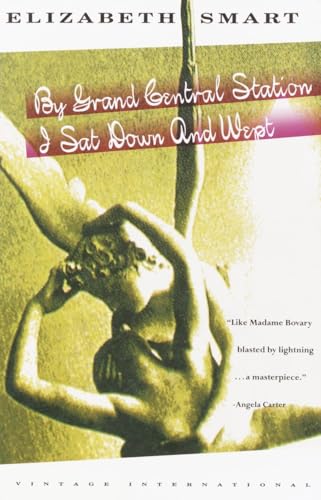

In the late 1930s, a Canadian poet named Elizabeth Smart chanced upon a volume of poetry in a bookstore. She was in her 20s, born into a wealthy family in Ottawa, educated expensively in Canada and then London, and had been traveling the world as a secretary to an older woman. In Better Books on Charing Cross Road in London, she lifted a volume of poetry from the shelf and the direction of her life was forever altered. The poet was George Barker. She fell in love with him through his work, and decided to marry him.

George Barker was married to someone else, but Smart seems not to have viewed this as an impediment. She eventually managed to track him down through Lawrence Durrell, they struck up a correspondence, and By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, widely viewed as a masterpiece of poetic prose, is a novelization of the affair that followed. “I want the one I want,” she wrote. “He is the one I picked out from the world.” In 1940, she used her clothing allowance to fly George Barker and his wife to California, where by that time she was living in a writer’s colony in Big Sur, and here Grand Central Station begins, with Smart waiting for her soon-to-be-lover’s arrival: “I am standing on a corner in Monterey, waiting for the bus to come in, and all the muscles of my will are holding my terror to face the moment I most desire.”

The moments of greatest tension lie in these early pages, when the affair hasn’t yet begun; when she waits, wracked with guilt, in the cottage next door to George Barker and his wife. “I do not beckon to the Beginning,” she writes, “whose advent will surely strew our world with blood.” And, of course, it does. In 1941, she was stowed away in Pender Harbor, British Columbia, lonely and pregnant with the first of her and George’s four children. (“Forty days in the wilderness and not one holy vision.”)

Her family tried to keep them apart, at once point exerting their influence to have George turned away at the Canadian border for “moral turpitude,” but he was the one she’d picked out from the world: she obtained employment as a file clerk at the British Embassy in Washington, and then followed Barker to England two years later. He visited her often in London, she became pregnant again and again, but they never married. “Her love for him was based on a literary obsession that started when she was young,” their son Christopher Barker wrote in The Guardian some years ago, “and was to remain her overriding passion all her life.”

The affair seems to have unfolded with a catastrophic inevitability. From Grand Central Station: “Jupiter has been with Leda, I thought, and now nothing can avert the Trojan wars. All legend will be broken, but who will escape alive?”

Here, a troubling note of subservience. In Greek mythology, Leda was seduced — or was raped — by a swan, and gave birth to Helen of Troy. Her legend is based entirely on copulation and parenthood. Jupiter, on the other hand, was the king of the gods.

3.

By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept is a staggering accomplishment, an exquisite and often ecstatic work. In one of the book’s most famous passages, Smart and Barker have been arrested in Arizona — apparently for having fallen afoul of morality laws — and her interview with a police officer is interlaced with lines from the Song of Songs:

But at the Arizona border they stopped us and said Turn Back, and I sat in a little room with barred windows while they typed.

What relation is this man to you? (My beloved is mine and I am his: he feedeth among the lilies.)

How long have you known him? (I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine: he feedeth among the lilies.)

Did you sleep in the same room? (Behold thou art fair, my love, behold thou art fair: thou hast dove’s eyes.)

In the same bed? (Behold thou art fair, my beloved, yea pleasant, also our bed is green.)

Did intercourse take place? (I sat down under his shadow with great delight and his fruit was sweet to my taste.)

When did intercourse first take place? (The king hath brought me to the banqueting house and his banner over me was love.)

But this is only the most obvious manifestation, the moment when the Song of Songs is allowed to rise to the surface; elsewhere it shimmers just beneath the prose. From the Song of Songs: “Who is she who comes up from the desert, leaning upon her beloved?”

“I am suddenly so rich,” Smart writes, of the affair’s early days, “and I have done nothing to deserve it, to be so overloaded. All after such a desert.” Later: “As the apple tree among the trees of the wood, so is my beloved.” The Song of Songs: “Like an apple tree among trees of the forest, so is my beloved among the youths…Sustain me with raisin cakes, refresh me with apples, for I am faint with love.”

4.

Faint with love, or otherwise compromised by it. In his piece in The Guardian, Christopher Barker paints a portrait of a woman caught in an obsession, unable or unwilling to see her lover’s faults. He describes his father as an intemperate, occasionally violent, and self-obsessed man, who treated the women in his life abominably — and there were many: George Barker fathered 15 children. Elizabeth Smart’s second prose poetry memoir, 1978’s The Assumption of the Rogues & Rascals, is a restrained, far more sober work than Grand Central. It isn’t hopeless, but ecstasy has been replaced by resignation: “I am old enough to know that nothing I want will ever happen. I might get a faded facsimile.”

Faint with love, or otherwise compromised by it. In his piece in The Guardian, Christopher Barker paints a portrait of a woman caught in an obsession, unable or unwilling to see her lover’s faults. He describes his father as an intemperate, occasionally violent, and self-obsessed man, who treated the women in his life abominably — and there were many: George Barker fathered 15 children. Elizabeth Smart’s second prose poetry memoir, 1978’s The Assumption of the Rogues & Rascals, is a restrained, far more sober work than Grand Central. It isn’t hopeless, but ecstasy has been replaced by resignation: “I am old enough to know that nothing I want will ever happen. I might get a faded facsimile.”

“She knew from the start,” Christopher Barker writes, “that the price of her love for her man would be high. It was, and more, but she clung desperately to the memory of the passion of those first moments of meeting, when ‘the muscles of my will held the terror for the moment I most desired.’ She would never renege on that and, tough though it was, to that moment she always remained true.”

In Christopher Barker’s telling, she was subservient to the literary men in her life; when writers and painters visited the family home in Paddington in the 1960s, the woman whose book had been hailed as a masterpiece of prose poetry “would race around as the general factotum and handmaiden, playing hostess to make sure that the great and serious minds of the men present were taken care of.”

George Barker is a troubling figure, but so is Elizabeth Smart. When she picked up the volume of poetry that day in the bookstore on Charing Cross Road, was she somehow unable to differentiate between the man and his work? More to the point, why did this woman — well-traveled, talented, intelligent, with a wealthy family behind her — align herself so completely with a man who treated her so poorly?

But then, other people’s relationships are always mysterious. A relationship is a closed world, and it’s impossible to see clearly into the interior from the outside. St. Bernard of Clairvaux: Only the singer hears it and the one to whom he sings. Only the external details are clearly visible: once there was a young and passionate poet who fell in love with a married man, and the affair inspired a magnificent work.

“Although I may never have understood her love for him,” Christopher Barker wrote of his parents, “I would always defend her inalienable right to her own self-sacrifice.”