1.

We tend to associate W.G. Sebald and his characters strongly with melancholy and sadness. “[T]he figures who populate Sebald’s world are lost souls,” Ruth Franklin has noted, “breaking beneath the burden of their own anguish.” Susan Sontag said that Sebald’s voice has a “passionate bleakness.” “W.G. Sebald’s books…have a posthumous quality to them,” Geoff Dyer stated. “He wrote — as was often remarked — like a ghost.” Others have written about Sebald’s “weary, melancholy wisdom” (Mark O’Connell) and his characters being “racked by conflict between a self-protective urge to block off a painful past and a blind groping for something, they know not what, that has been lost” (J.M. Coetzee).

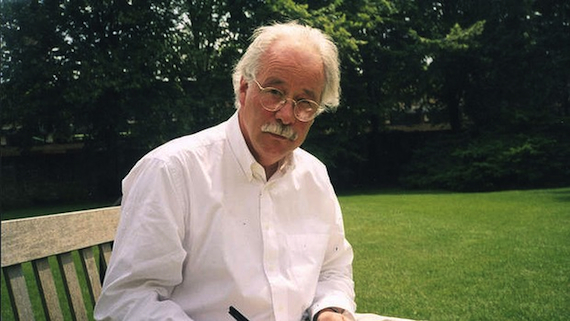

No wonder, then, that most everything written about W.G. Sebald, at least in the last dozen years, begins with his death. In 2001, Sebald was driving not far from his home in Norwich, England, with his daughter, Anna. We now know he suffered a heart attack, and the car, as a result, swerved into oncoming traffic, where it collided with a truck head-on. Anna, badly injured, survived. Perhaps it is because we connect Sebald so strongly with the past—and that his sad, sudden death seems as tragic as anything in his books— that we cannot get over his own passing. At only 57, and during the prime of a literary career that didn’t bloom until he was in middle age, Sebald left too soon. As much as Sebald wrote about the past — he noted in an interview he was “hardly interested in the future” because there was “something terribly alluring” about the past — we are obsessed with the future that wasn’t, with the books that he didn’t live to write.

Posthumously, however, a few books have been trickling into English, including Across the Land and the Water, a collection of poems; Campo Santo, a collection of essays on Corsica; and now A Place in the Country, a series of six essays on artists Sebald found inspirational. Although this book was first published in German in 1998, it only arrives now in English, translated by Jo Catling; in a way, Sebald has not died quite yet — at least not for us English-language readers.

Posthumously, however, a few books have been trickling into English, including Across the Land and the Water, a collection of poems; Campo Santo, a collection of essays on Corsica; and now A Place in the Country, a series of six essays on artists Sebald found inspirational. Although this book was first published in German in 1998, it only arrives now in English, translated by Jo Catling; in a way, Sebald has not died quite yet — at least not for us English-language readers.

Reading A Place in the Country, then, marks that sad Rubicon.

2.

“A Place in the Country” opens hauntingly enough, with a foreword written by the author, discussing his reasons for embarking on this work: “The unwavering affection for Hebel, Keller, and Walser,” Sebald writes, “was what gave me the idea that I should pay my respects to them before, perhaps, it may be too late.” (Even Sebald opens an essay with a oblique statement about his own death.) The bulk of the focus here is on German language writers — Eduard Mörike, Johann Peter Hebel, Gottfried Keller, Robert Walser — but the volume also includes a taut exploration of the hyperrealistic pictures of German painter and former Sebald classmate Jan Peter Tripp, and a masterful, long excursion (part travelogue, part biography) into the life of philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

I suspect there may be two essential audiences for this type of book. The first are the Sebald enthusiasts, who have gobbled down everything he has written; and the second are those who are genuinely interested in the artists Sebald explores. While the book may have some revelations for the latter group, it seems more likely the Sebald devotees will find more to like.

Each of these essays’ subjects could have fit into Sebald’s fiction — perhaps most especially in The Rings of Saturn, which most closely resembles nonfiction — although here they receive as deep of a consideration as any historical figure in the novels. The deepest and most profound analysis, rightfully, is for Walser, a writer who, Sebald says, “was only ever connected with the world in the most fleeting of ways” and for whom there exists “no reliable answer” as to what he was. Born in Switzerland, Walser was a lonely young ascetic — a “clairvoyant of the small” in his own words — who, Sebald reports, probably died a virgin and didn’t even possess copies of his own books. He only ended up famous posthumously, thanks to the work of Carl Seelig, his champion, who secured the cryptic pencil writings Walser had been incessantly working on toward the end of his life. But despite Seelig, Walser “remains a singular, enigmatic figure.” Here Walser seems a prototypical, aloof Sebald protagonist, akin to the nameless narrator of The Rings of Saturn, who says he sets off on a walk of Suffolk “in the hope of dispelling the emptiness that takes hold of me whenever I have completed a long stint of work.” Walser, perhaps the most famous literary walker after Sebald himself, may have been the model for this — and, to some extent, all the others. It is testament to Sebald’s command and distinctive imprint on our imaginations that Walser’s biography now seems utterly Sebaldian. Walser is almost as fine a Sebaldian character as Austerlitz, the eponymous protagonist of Sebald’s final novel.

Each of these essays’ subjects could have fit into Sebald’s fiction — perhaps most especially in The Rings of Saturn, which most closely resembles nonfiction — although here they receive as deep of a consideration as any historical figure in the novels. The deepest and most profound analysis, rightfully, is for Walser, a writer who, Sebald says, “was only ever connected with the world in the most fleeting of ways” and for whom there exists “no reliable answer” as to what he was. Born in Switzerland, Walser was a lonely young ascetic — a “clairvoyant of the small” in his own words — who, Sebald reports, probably died a virgin and didn’t even possess copies of his own books. He only ended up famous posthumously, thanks to the work of Carl Seelig, his champion, who secured the cryptic pencil writings Walser had been incessantly working on toward the end of his life. But despite Seelig, Walser “remains a singular, enigmatic figure.” Here Walser seems a prototypical, aloof Sebald protagonist, akin to the nameless narrator of The Rings of Saturn, who says he sets off on a walk of Suffolk “in the hope of dispelling the emptiness that takes hold of me whenever I have completed a long stint of work.” Walser, perhaps the most famous literary walker after Sebald himself, may have been the model for this — and, to some extent, all the others. It is testament to Sebald’s command and distinctive imprint on our imaginations that Walser’s biography now seems utterly Sebaldian. Walser is almost as fine a Sebaldian character as Austerlitz, the eponymous protagonist of Sebald’s final novel.

Nearly equally impressive to the Walser essay — although for different reasons — is the piece on Rousseau, the famous promeneur solitaire. Part travelogue and part biography, Sebald frames the essay around the period the famous philosopher spent on the Swiss Île de St-Pierre. Sebald first sighted the island in September of 1965, some 200 hundred years to the day that Rousseau found refuge there. It takes Sebald another 31 years, however, before he visits the island in 1996.

The Île de St-Pierre was the last redoubt Rousseau possessed in his native Switzerland, and was, he would later report, the place where he was the happiest. Rousseau spent much of his time on the island botanizing, writing ceaseless letters, and drafting a constitution for Corsica. The philosopher’s room was fitted with a trapdoor, to allow Rousseau to escape from visitors’ constant calls, and Sebald provides a memorable imagining of what must have happened there:

When one considers the extent and diversity of this creative output, one can only assume that Rousseau must have spent the entire time hunched over his desk in an attempt to capture, in the endless sequences of lines and letters, the thoughts and feelings incessantly welling up within him.

As he so often does so well, Sebald takes the sins and the tragedy of Rousseau — a man who abandoned all of his children, and who has been the subject of endless character studies and biographical attention — and pulls out something fresh: “No one…recognized the pathological aspect of thought as acutely as Rousseau, who himself wished for nothing more than to be able to halt the wheels ceaselessly turning within his head.” He has much in common with the four exiles in The Emigrants.

As he so often does so well, Sebald takes the sins and the tragedy of Rousseau — a man who abandoned all of his children, and who has been the subject of endless character studies and biographical attention — and pulls out something fresh: “No one…recognized the pathological aspect of thought as acutely as Rousseau, who himself wished for nothing more than to be able to halt the wheels ceaselessly turning within his head.” He has much in common with the four exiles in The Emigrants.

While the other German-language writers Sebald focuses on may have made less of an impression on us English-language readers, they are no less important to Sebald. In Keller, Sebald writes, “no other literary work of the nineteenth century can the developments that have determined our lives even down to the present day be traced as clearly…” Like Rousseau — who was a huge influence on Keller’s Green Henry — Keller was a similar victim of thought: for many years, Keller subjected himself to writing, to the “attempt to contain the teeming black scrawl which everywhere threatens to gain the upper hand, in the interests of maintaining a halfway functional personality.” This is a bleak notion of one’s art, but then again, Keller seemed to live a fairly bleak personal life: “From the very beginning, despite a deep need of and evidently inexhaustible capacity for love, Keller’s life was marked by rejection and disappointment.”

While the other German-language writers Sebald focuses on may have made less of an impression on us English-language readers, they are no less important to Sebald. In Keller, Sebald writes, “no other literary work of the nineteenth century can the developments that have determined our lives even down to the present day be traced as clearly…” Like Rousseau — who was a huge influence on Keller’s Green Henry — Keller was a similar victim of thought: for many years, Keller subjected himself to writing, to the “attempt to contain the teeming black scrawl which everywhere threatens to gain the upper hand, in the interests of maintaining a halfway functional personality.” This is a bleak notion of one’s art, but then again, Keller seemed to live a fairly bleak personal life: “From the very beginning, despite a deep need of and evidently inexhaustible capacity for love, Keller’s life was marked by rejection and disappointment.”

Of the avuncular Hebel, Sebald paints a somewhat sunnier portrait, as he does with Eduard Morike, who lived surrounded by women. Yet all — including Walser — Sebald cites as having a certain “unluckiness in love,” which Sebald connects with the beauty of their writing. This notion only seems somewhat silly in retrospect. To be fair, Sebald also cites these artists’ “very long memor[ies],” but one imagines they didn’t hone such an “adeptness at their craft” because of a couple bad breakups. (Or, in Keller and Walser’s case, the lack of a break-up at all.) But, in Sebald’s essays, these fuzzy bits of logic are few and far between — what we are left with is a striking series of stories and feelings, all connected in surprising ways. Ruth Franklin has said that Sebald’s life project was a “a drawing-out of connections primarily through language and image rather than narrative or causality.” In that way, A Place in the Country is a rousing success.

3.

If one was hoping for more insight into the author himself (as I admittedly was), this volume may disappoint. Instead of the mischievous narrators of his fiction — nearly always sharing significant details with Sebald, such as a similar hometown or profession, or through the use of photographs actually taken by Sebald himself — we receive only fleeting, if transparent, glimpses of the writer beneath. (The most interesting may be the importance of his grandfather in Sebald’s life.) But what the book may lack in personal revelations about the author, it makes up for with a better understanding of his process — “an oblique comment on his own style of writing,” as translator Jo Catling notes in her foreword. Much can be gleaned from Sebald’s careful analysis of Hebel and Walser.

Anything more direct and personal would probably have not been fitting, anyway. Sebald’s writing is as much about what is written on the page as what cannot be. (“What Sebald seems to be writing about, in other words,” Mark O’Connell astutely observed, “is frequently not what he wants us to be thinking about.”) It is elliptical, because, it seems, some things have to be; words cannot describe every feeling, every sensation — no matter how many we write — and of all multitudinous topics that would be tough to grasp, perhaps the complexities and depths of our own selves are the most difficult. Even the prodigious Rousseau, Keller, and Walser could not contain half of everything in their works. Walser claimed to be always writing the same book, a novel which could be described as “a much-chopped up or dismembered Book of Myself.” We can take much from the fact he was scribbling up until the very end.

The authors in this volume, Sebald writes, have given him “the persistent feeling of being beckoned from the other side.” Sebald has now become one of these ghosts, haunting us still. Writers “are expected to keep writing until the pen drops from their hand.” Even though the pen was taken from his grasp far too early, we are lucky that Sebald, for a time, held it firm.

Image via Wikimedia Commons