Apéritif

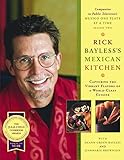

Michelle Wildgen had established her reputation as the resident gourmand in Tin House’s New York office, where she was then managing editor, long before I set foot there in the mid-aughts. In need of obscure spices, olive oil, fresh mozzarella? Michelle would promptly send you up to 125th Street, down to Vinegar Hill, off to an Italian neighborhood in the Bronx. She regaled the office with English toffee before the winter holidays, showing her behind-the scenes-mastery of the candy thermometer. Rumor of an enigmatic past as a cheese reporter in Wisconsin trailed her. It became obvious, quickly, that for Michelle, food was central as a medium, as a subject, as a way of life. She gave me recipes for dishes I loved to eat but didn’t know the first thing about how to approach. Chana masala, for example, which at that point I ordered from an Indian joint in my neighborhood at least twice a week. Upon request, she also supplied me with a list of must-have cookbooks, which included Nigel Slater’s Appetite, the perennial classic Joy of Cooking, and Rick Bayless’s Mexican Kitchen. Part of me still holds on to the idea of becoming a culinary goddess, but with each passing bout of inspiration I’ve learned that this desire to up the ante in the kitchen only lasts until I’m confronted by my own knives and cutting board and sink. This doesn’t diminish the pleasure I take in dining, of course, or overhearing an explicit description of a lavish feast. And so, for a while I lived vicariously while working with Michelle and listening to her mastery and enthusiasm for food, her robustness of detail. Those were hopeful years for me.

Michelle Wildgen had established her reputation as the resident gourmand in Tin House’s New York office, where she was then managing editor, long before I set foot there in the mid-aughts. In need of obscure spices, olive oil, fresh mozzarella? Michelle would promptly send you up to 125th Street, down to Vinegar Hill, off to an Italian neighborhood in the Bronx. She regaled the office with English toffee before the winter holidays, showing her behind-the scenes-mastery of the candy thermometer. Rumor of an enigmatic past as a cheese reporter in Wisconsin trailed her. It became obvious, quickly, that for Michelle, food was central as a medium, as a subject, as a way of life. She gave me recipes for dishes I loved to eat but didn’t know the first thing about how to approach. Chana masala, for example, which at that point I ordered from an Indian joint in my neighborhood at least twice a week. Upon request, she also supplied me with a list of must-have cookbooks, which included Nigel Slater’s Appetite, the perennial classic Joy of Cooking, and Rick Bayless’s Mexican Kitchen. Part of me still holds on to the idea of becoming a culinary goddess, but with each passing bout of inspiration I’ve learned that this desire to up the ante in the kitchen only lasts until I’m confronted by my own knives and cutting board and sink. This doesn’t diminish the pleasure I take in dining, of course, or overhearing an explicit description of a lavish feast. And so, for a while I lived vicariously while working with Michelle and listening to her mastery and enthusiasm for food, her robustness of detail. Those were hopeful years for me.

Salad:

Food plays a central, steady, and rather predictable role in most of our lives. Three meals a day, coffee with breakfast, nightcap before bed. Or, if that’s not right, perhaps it’s coffee for breakfast, tuna salad for lunch, dinner out, and a nip of dark chocolate after? To each her own. Continuing to consume is necessary to continue living but this ongoing cycle of hunger and feeding doesn’t usually incite a predicament in the way that narrative fiction requires.

And just how many meals do characters prepare? How many do they eat? Oh, there are significant meals. There are wedding banquets and funeral meats. The tears of longing that fall into the wedding cake batter in Laura Esquivel’s Like Water For Chocolate afflicts each wedding guest who has a piece. Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus ends with a banquet where the guests are served a pie filled with meat cut from the bodies of Titus’s daughter’s assailants. Marcel Proust’s Swann’s Way is forever linked to the madeleine because of an ecstatic memory of a morsel of that small French cake. And that’s not Proust’s only paean to food in Swann’s Way. His description of the kitchen scullions at work and the rows of all things vegetables sent me into a deep hunger the first time I read it:

And just how many meals do characters prepare? How many do they eat? Oh, there are significant meals. There are wedding banquets and funeral meats. The tears of longing that fall into the wedding cake batter in Laura Esquivel’s Like Water For Chocolate afflicts each wedding guest who has a piece. Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus ends with a banquet where the guests are served a pie filled with meat cut from the bodies of Titus’s daughter’s assailants. Marcel Proust’s Swann’s Way is forever linked to the madeleine because of an ecstatic memory of a morsel of that small French cake. And that’s not Proust’s only paean to food in Swann’s Way. His description of the kitchen scullions at work and the rows of all things vegetables sent me into a deep hunger the first time I read it:

I would stop by the table, where the kitchen-maid had shelled them, to inspect the platoons of peas, drawn up in ranks and numbered, like little green marbles, ready for a game; but what most enraptured me were the asparagus, tinged with ultramarine and pink which shaded off from their heads, finely stippled in mauve and azure, through a series of imperceptible gradations of their white feet — still stained a little by the soil of their garden-bed — with an iridescence that was not of this world.

Proust’s peas and asparagus evoke the 19th-century still lives of Édouard Manet, whose numerous depictions of kitchen stock and cuisine include a hare hung by the legs and a platter of raw oysters accompanied by lemon wedges. Consider also Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons and its portraits of food. The rhythm and sound come together to convey the object’s essence, making Stein’s “Asparagus” a different stripe than Proust’s. But Stein’s cubist rendering also aspires to art: “Asparagus in a lean in a lean to hot. This makes it art and it is wet wet weather wet weather wet.”

Main Course:

A chef knows how to stiffen the egg whites so that the soufflé stands; a fiction writer develops a sense of how to craft sentences and paragraphs to support the narrative and its central characters. There are prescriptive recipes for many types of writing just as there are for all kinds of dishes, and yet the ability to follow directions is more skill than art. It’s only after the procedures are internalized and diverged from that both cook and writer can pull off an original concoction.

Perhaps in this way, writing a novel is similar to planning a feast.

Wildgen’s depictions of food hew closer to Proust’s than Stein’s in that they are indulgent and languorous. And she’s as skilled at the mechanics of whipping up a well-crafted story as she is describing how to make a béarnaise. In her essay “Ode to an Egg” Wildgen confronts the egg, a character that is both pliable and stubborn: “Faced with gracelessness, an egg asserts itself…Just try skipping the tempering of beaten yolks with warm liquid before adding them to a béarnaise and watch the egg clench its proteins like fists. You will be no more successful with a chilly egg yanked from the fridge than you will with a date you have shoved into a swimming pool.” And yes, her fiction contains an abundance of edibles, too. In her first novel, You’re Not You, the narrator, Bec, is a young college student who takes a job as a caretaker for a woman afflicted with Lou Gehrig’s disease. The novel is peppered with vivid scenes of shopping in Madison’s farmer’s market, among the cascades of vegetables, cheeses, and meats. Wildgen’s second novel, But Not for Long, is set within a food co-op, and now, her latest, Bread and Butter, is nestled firmly in the restaurant industry as it follows three restaurateur brothers. Leo, the businessman, works in partnership with Britt, the charmer who oversees the front end of their well-established restaurant Winesap; and Harry, their upstart younger brother who wants to make his mark decides to open his own, edgier place, Stray.

Wildgen’s depictions of food hew closer to Proust’s than Stein’s in that they are indulgent and languorous. And she’s as skilled at the mechanics of whipping up a well-crafted story as she is describing how to make a béarnaise. In her essay “Ode to an Egg” Wildgen confronts the egg, a character that is both pliable and stubborn: “Faced with gracelessness, an egg asserts itself…Just try skipping the tempering of beaten yolks with warm liquid before adding them to a béarnaise and watch the egg clench its proteins like fists. You will be no more successful with a chilly egg yanked from the fridge than you will with a date you have shoved into a swimming pool.” And yes, her fiction contains an abundance of edibles, too. In her first novel, You’re Not You, the narrator, Bec, is a young college student who takes a job as a caretaker for a woman afflicted with Lou Gehrig’s disease. The novel is peppered with vivid scenes of shopping in Madison’s farmer’s market, among the cascades of vegetables, cheeses, and meats. Wildgen’s second novel, But Not for Long, is set within a food co-op, and now, her latest, Bread and Butter, is nestled firmly in the restaurant industry as it follows three restaurateur brothers. Leo, the businessman, works in partnership with Britt, the charmer who oversees the front end of their well-established restaurant Winesap; and Harry, their upstart younger brother who wants to make his mark decides to open his own, edgier place, Stray.

Food is the true currency of Bread and Butter. Food is an art, a language of affection, of consolation, a way of life. The culinary imperative is present from the opening scene, where a young Harry buys a lamb’s tongue with his allowance. The long, lingering pass over the butcher’s case establishes the narrative eye as unflinching and artful:

Inside a butcher’s case, denuded rabbits curled pink and trusting in white bins, while the sheep’s heads appeared chagrined and surprised by the depth of their eyeballs, the narrow clamp of their own teeth. The display of calves’ brains and kidneys, livers and tripe, repulsed Britt, struck Leo as regrettable but unavoidable, and entranced Harry who was six.

The brothers’ reactions foretell much about their future adult selves, from Leo with the rational mind to Harry the adventure seeker. Their lives are defined in relation to food. This is true whether Leo and Brit worry about whether their warm chocolate cake has become outdated, or when the Harry argues for keeping a provocative dish on his menu: “you’ve also gotta give people something they haven’t tasted, something they can’t imagine and have to come in and try.” And, well, this scene also provides fair warning for readers who find so much meat unsavory, much like Momofuku’s Ssäm Bar whose the menu of which announces, “We do not serve vegetarian-friendly items.”

Human behavior is observed within the context of the rules of the trade (and the rules that are broken): don’t date coworkers; the staff is young, desirable, and often temperamental; key players in the kitchen will be lured and poached by other establishments; extreme focus is required during rushes, when on a good day the kitchen and wait staff merge into complimentary sides of a well-oiled machine. And the food! If nothing else (and there is plenty else), the novel revels in its cuisine. Sentences are peppered with exquisite dishes throughout and take detailed note of the textures and presentation and garnishes, allowing reader gorge. Dishes served include pig’s ear, hard salami, putty-colored lambs tongue, rabbit ragù with pappardelle, salted brittle, and sardines. An entire hog has been butchered and transformed into barbeque and charcuterie for a staff party. This physicality grounds the brothers’ struggles, caught up in assuring Winesap’s relevance as Stray establishes its name. When Britt first tastes Harry’s signature dish of lamb’s neck with Jerusalem artichokes he’s concerned that it’s too adventurous to lure small town diners. The same dish dazzles Leo and makes him worry he’s become too complacent. It’s the kind of conundrum that plagues the brothers, as well as all forms of art and commerce — the inspired dish won’t lure diners despite its brilliance, while the reliable dishes that sell are often staid.

Dessert:

Bread and Butter is a tremendous feast of a novel. Like a meal served at the streamlined Winesap, it adheres to a more classic ideal of what makes a book worth reading. It doesn’t aspire to rework the novel as form, nor does it attempt to. Instead, it achieves with excellence what it sets out to do, with its well-crafted characters and the subtle development of their entanglements, as it offers an insider’s view view of the restaurant industry, including the struggle to balance business and creativity, the intermingling of family and business, and of course, the cuisine. The food’s physicality is so palpable and inviting, and is rendered with precision and balance — this too is art. I’ll leave you with a morsel to whet your appetite, as Harry serves the lamb’s neck: “He drew something meaty and brown, dripping, from a braising pot and set it on a metal dish and slid it into the oven. Then he arranged some crisp root vegetables and broccoli rabe on a round white plate, placed the meat at the center, and scattered the whole thing with something golden and green and finely chopped. He placed this before Britt with the air of a cat delivering a freshly killed gopher.”