Pity the novel. Once upon a time it was a big, baggy story told in chronological order by an omniscient narrator. Over time, it’s been marginalized, shunned, belittled, banned, and more recently, broken into pieces that vie with each other to make a cohesive whole. You could blame dwindling attention spans, pared down by digital toys. It’s ancient history that any TV viewer can either reorder or skip scenes at home. Now we spend a day streaming series that took years to air, let alone produce. The consequences of contemporary viewing preferences are the random jumbling of storyline, as well as time’s transposition and compression. Why wouldn’t novels follow suit?

When I first started thinking about this, I looked for parallels with how we share personal stories in our increasingly scarce private lives. Individual narratives are never linear, nor do we recount them to each another in a linear fashion. Small wonder that contemporary novels unfold out of order.

And yet, I’m sure there’s more. Michael David Lukas, reaching into the musical lexicon to examine novel developments, used the term “polyphonic” (referring to a chorus or multiplicity of voices) to make an intriguing argument: “Polyphony widens the novel’s geographic, psychological, chronological, and stylistic range, while simultaneously focusing its gaze.”

Lukas cites Nicole Krauss’s Great House and Tom Rachman’s The Imperfectionists. Categorized as “novels,” these books are linked short stories with a common item or thread running through the chapters. In Great House, it’s a desk; in The Imperfectionists, it’s the characters’ association with an English language newspaper published in Rome. More recently, Ayana Mathis’s The Twelve Tribes of Hattie has a character — Hattie — who serves as the common element. Lukas uses “polyphony” to describe novels that further increase structural complexity by inverting time and space. For example, David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas is populated with seemingly unrelated characters, geography, and time periods. Bob Shacochis’s The Woman Who Lost Her Soul shares similarities. The action is set against historical events that are presented out of chronological order within diverse geographies and between seemingly unrelated protagonists.

Lukas cites Nicole Krauss’s Great House and Tom Rachman’s The Imperfectionists. Categorized as “novels,” these books are linked short stories with a common item or thread running through the chapters. In Great House, it’s a desk; in The Imperfectionists, it’s the characters’ association with an English language newspaper published in Rome. More recently, Ayana Mathis’s The Twelve Tribes of Hattie has a character — Hattie — who serves as the common element. Lukas uses “polyphony” to describe novels that further increase structural complexity by inverting time and space. For example, David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas is populated with seemingly unrelated characters, geography, and time periods. Bob Shacochis’s The Woman Who Lost Her Soul shares similarities. The action is set against historical events that are presented out of chronological order within diverse geographies and between seemingly unrelated protagonists.

Ted Gioia, a musician and writer, followed Lukas with an essay written in fragmented bits of text, probing why the novel is breaking up, accompanied by an ambitious 57-volume booklist.

Gioia places the fracturing novel in a broad cultural context that includes Thelonious Monk as the “jazzman of fragmentation” and Wittgenstein as its philosopher. Applauding the current fragmenters for successfully navigating literary complexity and traditional storytelling (aka plot), Gioia affirms that despite fission, novel craft is improving. Even if master short story writer Alice Munro were not the most recent Nobel laureate, every writer worth her salt knows that writing lean is far more difficult than producing the more leisurely, lazy, lengthy counterpart.

Except that novels are swelling again. Not only did last year’s Booker Prize winner, Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries clock in at 848 pages, but several equally celebrated books boast equivalent heft, including Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, Elizabeth Gilbert’s The Signature of All Things, and Shacochis’s The Woman Who Lost Her Soul.

Why? Ted Gioia offers a theory. “All experimental approaches in the arts can perhaps be divided into two categories — experiments of disjunction or experiments of compression. Either things get pushed apart, or get squeezed together. Either an aesthetic of disintegration, or an aesthetic of wave-like flow.”

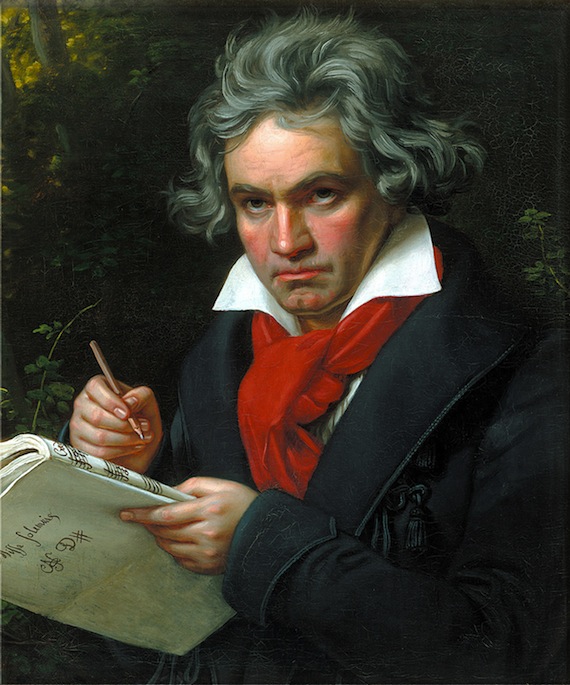

The Grand Experimenter, it turns out, was Ludwig van Beethoven. This musical colossus, completely deaf, his personal affairs in chaos, perennially behind in his finances, unwell and unloved, reworked the string quartet in ways that continue to bewilder and astonish. The six late quartets, for two violins, viola, and cello, were composed within two years of Beethoven’s death in 1827. They are called by their opus numbers: 127, 130, 131, 133, 132, 135 (don’t ask about numerical order). These pieces span the experimental pendulum’s trajectory. The composer not only fractured, he compressed and expanded as well.

Beethoven’s earlier quartets and those of his predecessors and successors as well, generally have four movements: a lively opening, a slow second movement, a “minuet and trio” movement beat in three (the order of the second and third are often reversed), and an authoritative final movement. Around structure, Beethoven went rogue with his late quartets. He took the traditional four-movement quartet, split it up, and then both condensed and augmented it. Opus 130 has six movements as opposed to the usual four; Opus 131 has seven that are played/performed without a break as one long movement; and Opus 132 has five. Opus 133, the Grosse Fugue, is a one-movement leviathan. It was meant to be the sixth and final movement to Opus 130, but was horrendously difficult and got an appalling reception. “I think, with Voltaire, ‘that a few gnat-stings cannot arrest a spirited horse in his course,’” Beethoven said of critics. However, he bowed to outside pressure and lopped off the Grosse Fugue, publishing it as a stand-alone composition. Then wrote a frothy new ending that was the last piece he completed.

Within these overarching structures, Beethoven took traditional form and forged new trails. For example, he quarried the unconventional from the garden-variety “minuet and trio” movement. All but two of the late quartets contain such a movement, beat in three according to the rules, and organized thematically just as Haydn or Mozart would have done. In these movements, however, Beethoven plays with rhythm by blurring the lines between measures. He foreshortens melodic line and accelerates tempo. In other words, most of these movements go at breakneck speed and/or the tune is too fractured to sing along.

Beethoven took another well-known form, the theme and variations movement, and stretched and deepened it in new ways. Opus 127’s second movement opens with an austere violin melody that sets the theme for the variations that follow. The movement is immense, vastly longer than the slow movements of string quartets that preceded it, including previous slow movements that Beethoven had written. Here the composer takes his time on a grand scale, luxuriating in the breadth and depth of his melodic creation.

The fugue, a melody introduced by one instrument that is subsequently taken up by another instrument, appears in many string quartet movements. (Think of a round, where the melody travels through various voices and is inverted and lengthened throughout the course of the piece.) Beethoven’s Grosse Fugue, however, is in a class by itself. It is the longest of Beethoven’s late quartet movements. Talk about dense. With its abrupt, ruptured bursts of sound, the Grosse Fugue is virtually inaccessible on first hearing. Like the 20th-century music that was to follow, the Grosse Fugue is dissonant. There are long stretches where rhythm elbows out melody, relentless beats without much tune.

One hundred ninety years ago, Beethoven was covering the experimental spectrum, fragmenting and enlarging within the space of a few short years. His late quartets fluctuate between slower, lyrical movements and faster movements with short, chopped up melody, compacted rhythms, interrupted tempos, and challenging key signatures. He deployed the four instruments (voices) in novel ways, assembled new harmonies, smashed rhythmic convention, messed with dynamic (volume) markings, upended time signatures, and a whole lot else. Including inspiring countless artists; for example, T.S. Eliot and the Four Quartets.

Beethoven may have turned out to be the Grand Experimenter, but did he actually set out to experiment? Radical innovation may be the consequence, rather than the cause, of self-expression at this stratospheric level. Some combination of genius and drive spurred Beethoven’s compositional feats. To satisfy the demands of his genius, Beethoven tilled new musical ground.

His deafness must have played a central role. Beethoven’s ability to compose through the deafness does not speak to his musicality per se. Any well-trained composer can pick up a score and understand what’s on the page without playing it. Beethoven’s deafness speaks instead to something deeper. In his early 30s, 15 years before his death, Beethoven prepared a document for his brothers. Named for the place it was written, Beethoven’s “Heiligenstadt Testament” bears witness to the despair and isolation caused by his deafness, as reprinted in Thayer’s Life of Beethoven:

Though born with a fiery, active temperament…I was soon compelled to withdraw myself, to live life alone. If at times I tried to forget all this, oh how harshly was I flung back by the doubly sad experience of my bad hearing…How could I possibly admit an infirmity in the one sense which ought to be more perfect in me than in others, a sense which I once possessed in the highest perfection, a perfection such as few in my profession enjoy or ever have enjoyed…For me there can be no relaxation with my fellow-men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas. I must live almost alone like one who has been banished…

Despite being the most accomplished musician of his day, Beethoven became unable to perform his piano concertos because he could not hear the orchestra. He was thwarted from conducting his symphonies and from playing his chamber music. In short, at the apex of his musical powers, he was prevented from participating in the joy of his own creation, forced to plumb the music in silence.

Silence birthed late Beethoven — music of profound and unparalleled emotional range. What did Beethoven discover within the silence? Certainly he found the freedom to buck convention and strike out on his own. But within the silence, he accessed something more: the arduous, agonizing road to his own mortality. The late quartets contain movements of such introspection and depth that to partake in the composer’s grief becomes a sublime, transformative experience. This musical giant is frustrated and raging, tormented by illness and loneliness, wrestling with the divine. We hear him grappling to make his peace.

There isn’t a more majestic, reflective hymn than the fifth “Cavatina” movement to Opus 130. Beethoven himself said that nothing he had written so moved him; in fact “merely to revive it afterwards in his thoughts and feelings brought forth renewed tributes of tears,” according to Thayer’s Life of Beethoven. Or the transcendent otherworldly opening of Opus 131. And Beethoven’s rare commentary to Opus 132’s third movement summons the divine directly, “Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der lydischen Tonart” — “A Convalescent’s Holy Song of Thanksgiving to the Divinity, in the Lydian mode.” The spare, deliberate simplicity of this movement is music of the spheres. The quartet’s final movement combines longing with agitated dissonance, delivering a sense of cosmic urgency.

In the last substantial work Beethoven finished — Opus 135 — the listener travels through sanctified territory, accompanying Beethoven to his death. Beethoven’s notes to Opus 135’s fourth movement, printed in the final manuscript above a nine-note tune, read: “’Der Schwer Gefasste Entschluss.’ Muss es sein? Es muss sein! Es muss sein!” — “‘The Difficult Decision.’ Must it be? It must be! It must be!”

Except that these words are not what they seem. A story that circulated during Beethoven’s time was that the tune came from a canon Beethoven had penned to capture a patron’s reaction to unwelcome news; Herr Dembscher had been told that to obtain a quartet manuscript for a party he wanted to host, he would have to pay 50 florins.

Perhaps these imponderables are meant to remain so; for example why the novel is shrinking or fracturing or expanding or twisting itself into something else. No matter. Writers pursuing their creative ends are apt to reinvent the medium for a long time.

Image Credit: Wikipedia