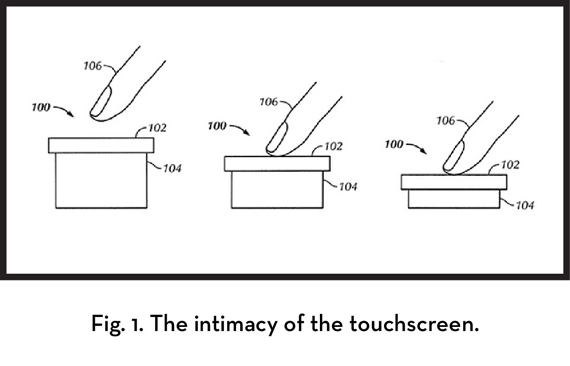

Ever since its introduction a little over six (!) years ago, the iPhone and all of its portable touchscreen iterations have fundamentally altered the way we process information, interact with one another, and document our surroundings (through faux, overexposed photographs). The deceptively simple interface of finger against glass proved to be the key to unlocking an unprecedentedly intimate feedback loop between user and device. And yet I believe I am not alone when I say that such intimacy has left me straddling what feels like two warring halves of myself. On the one hand, there is the part of me that appreciates nothing more than the quiet smolder of a 600-page novel’s unfolding narrative. Such stories are slow, multivalent; they demand deep periods of our attention in order to attain a delayed payoff that ultimately resonates far beyond the pages of the book. And then there is the dopamine-addicted part of me that is constantly reaching for my iPhone to monitor a world that has essentially not changed since I last checked up on it five minutes ago. This part of me feels weirdly naked if I leave the house without that little rectangular chunk of metal and glass in my pocket.

Like many of you, I cannot help feeling that these two halves are locked in some kind of existential battle; that deep, long-form literary storytelling is incompatible not just with the 140-character lifestyle we are being to trained to embrace, but also with the very architecture of a small, handheld touchscreen. Such a device intrinsically demands to be continuously shuffled in and out of the pocket. Such a device demands—through its shape, size, and interface—enough of your attention to keep you satiated, but not enough to keep you truly engaged.

And yet, even in my moments of deepest technopocalyptic pessimism, I also know that there are many exciting opportunities to utilize the touchscreen interface as an innovative platform for telling stories. But let us be blunt: even just that antiseptic word “interface” usually spells doom for conjuring any kind of poetic experience. Print books are still far and away the best interface we’ve got. I’ve waded through enough of those clumsy, masturbatory hypertext disasters that were so en vogue in the ‘90s to know that, contrary to what Robert Coover or others might say, true interactivity is rarely a good thing when it comes to authentic literary pathos. At the end of the day, the reader wants to feel the soft hands of the writer guiding them down the path. Narrative strength arises from narrative finitude.

Several years ago, Jeff Rabb and I set about designing an iPad version of my first novel, The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet. Cognizant of the slippery slope offered by interactive platforms, we tried to embrace the unique opportunities that a boundless touchscreen has to offer — links, partially obscured (yet retrievable) text, birds-eye navigation maps — but then also temper these opportunities with the lessons of the bounded, curated (i.e. limited) printed page. In my mind, the goal for writers and designers should be to learn from print books and not simply emulate them on a screen, as the first generation of e-books did and continue to do (hello skeuomorphic page-turning animation????). Yet despite countless hours of careful consideration, the iPad adaption of my book was still a little bit awkward, in part because it was exactly that: an adaptation, a work designed for the page that had been exported to the tablet.

Several years ago, Jeff Rabb and I set about designing an iPad version of my first novel, The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet. Cognizant of the slippery slope offered by interactive platforms, we tried to embrace the unique opportunities that a boundless touchscreen has to offer — links, partially obscured (yet retrievable) text, birds-eye navigation maps — but then also temper these opportunities with the lessons of the bounded, curated (i.e. limited) printed page. In my mind, the goal for writers and designers should be to learn from print books and not simply emulate them on a screen, as the first generation of e-books did and continue to do (hello skeuomorphic page-turning animation????). Yet despite countless hours of careful consideration, the iPad adaption of my book was still a little bit awkward, in part because it was exactly that: an adaptation, a work designed for the page that had been exported to the tablet.

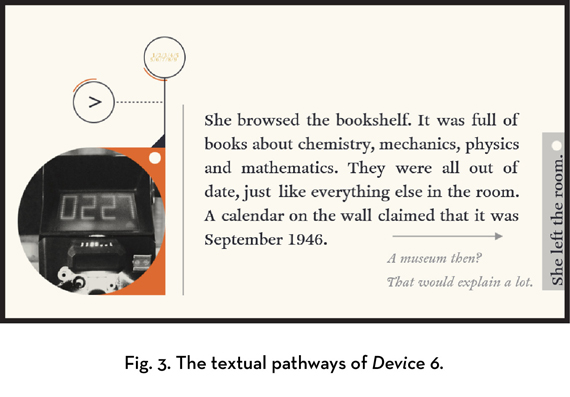

So perhaps it is fitting that one of my favorite works of this year, Device 6, is a book that was designed specifically for the touchscreen. Actually, I’m not quite sure if it’s even a book or even what a book is anymore. (Perhaps such a term is too limiting — maybe we need to develop a more sophisticated nomenclature like the Japanese in order to better describe a taxonomy of literary technologies.) Created by Simogo (Simon Flesser and Magnus Gardebäck) out of Malmö, Sweden, Device 6 is the first touchscreen literary creation that succeeds in blending the medium with its content to great and wondrous effect. Device 6 borrows from all kinds of sources, including the stutter-step pacing of those old Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Books, the minimalist interactivity and wayfaring of early interactive fiction games like Zork and Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the evocative, aural landscapes of classic radio dramas, the lush graphical enigmas of the Myst games, the nested, textual interplay of Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves, and of course, the creepy, false-naive cat’s cradle of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Yet somehow Device 6 manages to distinguish itself from all of these precursors by utilizing the very technology it is built upon — our dependency on our touchscreens — as its central conceit.

We navigate through each chapter of Device 6 by scrolling along little pathways of text and image, following our heroine Anna (a modern day Alice) as she explores a surreal island filled with automatons, looped recordings, and abandoned lighthouses. These textual pathways turn left and right, up and down, backwards and in spirals. We are asked to rotate the touchscreen around in our hands, to flick the words this way and that, and in so doing, we become complicit in the narrative; we are just as disoriented, just as searching as dear Anna. The modernist ‘60s graphics are reminiscent of Saul Bass — all clean dotted lines, Dewey Decimal labels, and translucent pastel arrowheads. Beneath it all, the impeccable sound-design perfectly undergirds your movement through the story with footsteps, door-clicks, or white-noise from an unseen radio. Like good prose, the sonic landscape suggests without demanding; it evokes without explicating. Indeed, during the whole reading/playing experience, you are taken by an unsettled feeling of urgency and descend into what feels like a finely calibrated mood, just as if you were working your way through a masterfully paced novella.

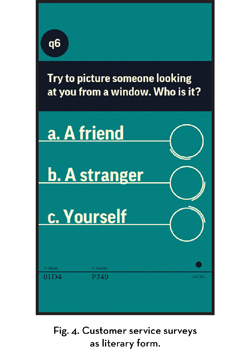

That question of verbiage — are you reading or are you playing? — seems to get at the heart of the matter. Late in the story, as your and Anna’s experience begin to converge, Anna, overtaken by deja-vu, muses about such confusion: “I know this place. I’ve been here before. No, wait. I’ve read about this place. But…how? Maybe it was a book. No…not a book. A…game?” Device 6 does break certain traditional literary conventions in that each “chapter” has a series of puzzles you must solve before you can move onto the next. For some, this may disqualify the piece from the genre of the literary and move it firmly into the domain of “video game,” but for me such a distinction is much trickier, for only occasionally do the puzzles feel superficially attached to the story. The format works because, in the end, the very process of your code-breaking becomes the story itself. This also goes for the strange interstitial questionnaires that come between chapters. Initially, they resemble some kind of quirky costumer service survey that Simogo might’ve cleverly woven into its product. But very quickly these questions go off the rails, leaving one to wonder what possible valuable information they could be providing for the game designers. And then you realize the questions are not for them but for you. Such is the nature of this creation: everything about Device 6 — including your reading/playing experience — is anticipated by the narrative framework of the book/game.

That question of verbiage — are you reading or are you playing? — seems to get at the heart of the matter. Late in the story, as your and Anna’s experience begin to converge, Anna, overtaken by deja-vu, muses about such confusion: “I know this place. I’ve been here before. No, wait. I’ve read about this place. But…how? Maybe it was a book. No…not a book. A…game?” Device 6 does break certain traditional literary conventions in that each “chapter” has a series of puzzles you must solve before you can move onto the next. For some, this may disqualify the piece from the genre of the literary and move it firmly into the domain of “video game,” but for me such a distinction is much trickier, for only occasionally do the puzzles feel superficially attached to the story. The format works because, in the end, the very process of your code-breaking becomes the story itself. This also goes for the strange interstitial questionnaires that come between chapters. Initially, they resemble some kind of quirky costumer service survey that Simogo might’ve cleverly woven into its product. But very quickly these questions go off the rails, leaving one to wonder what possible valuable information they could be providing for the game designers. And then you realize the questions are not for them but for you. Such is the nature of this creation: everything about Device 6 — including your reading/playing experience — is anticipated by the narrative framework of the book/game.

Do I want the trajectory of fiction over the next 50 years to be a slow slide from the 600-page novel to various iterations of game/story smartphone amalgamations like Device 6? Do I want some kind of interactive puzzle to become a prerequisite for any reading experience? Most decidedly, no. But I don’t think that’s what’s going on here. Device 6 doesn’t so much feel like a shortcut as the beginning of a long, important conversation. It is that rare example of talented people crafting gorgeous, smart multimedia creations that push us to reconsider our love of mystery as well as our love of the home button. Can these two impulses exist in harmony? Read/play Device 6 and decide for yourself. Just be sure to send me a tweet afterwards.

More from A Year in Reading 2013

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions’ Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions’ Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.