First published by New Directions as The Lazy Ones in 1949, the newly christened and reissued Laziness in the Fertile Valley by the Egyptian-born writer, Albert Cossery, will appear in bookstores this November in time for his centenary. New Directions has included a foreword by Henry Miller and this new afterword by the writer Anna Della Subin who uses Cossery’s oeuvre as a guide to the Egyptian Revolution.

First published by New Directions as The Lazy Ones in 1949, the newly christened and reissued Laziness in the Fertile Valley by the Egyptian-born writer, Albert Cossery, will appear in bookstores this November in time for his centenary. New Directions has included a foreword by Henry Miller and this new afterword by the writer Anna Della Subin who uses Cossery’s oeuvre as a guide to the Egyptian Revolution.

The lazybones attracts all the waves of the sea. “Let me sleep,” he begs, “so nice and warm under my white sheets and blue blankets.” And would you believe it? The sun’s on his side.

— Edmond Jabès, 1945

1.

Fasten a mast to the bed, let the sheets catch the wind. It is possible that, if you drift long enough on the waves of sleep, you will awaken into a world that has changed — though who can say for the better? The Greeks told of the boy Epimenides, who was searching for his father’s stray sheep when he stopped for a noonday nap in a cave. When he awoke, fifty-seven years later, everything that he once knew had vanished. Across Crete, news spread that Epimenides must be particularly loved by the gods to have slept so long. For Aristotle, he was proof of the impossibility of the passage of time without the occurrence of change.

Christian martyrs have dozed longer still. The eighteenth chapter of the Quran — and an earlier Syriac legend — tells of a group of young Christian men who, fleeing the persecution of a Roman Emperor, escaped into a cave, where they slumbered for three hundred and nine years. Rising from their long sleep, they found their beards had grown long, Christ’s name was openly spoken, and all of their loved ones were dead. In 1933, the Egyptian playwright Tawfiq al-Hakim dramatized their swim through the oceanic night in The People of the Cave. Awakening into a world where they are hailed as saints, the stiff-limbed sleepers find they cannot live in this strange, undreamt future. “We are like fish, whose water has changed from sweet to salty,” the saints protest, as they retreat into their cave.

Languishing in a French prison in 1883, Paul Lafargue observed that a strange mania had lately gripped mankind. It seemed everyone had begun to worship what their God had damned. In their canonization of work — that vampire sucking the blood of modern society — they had forgotten His sublime example. Did He not toil for six days, then rest forever after? In his treatise The Right to Be Lazy, Lafargue intoned a prayer: “O, Laziness, have thou mercy upon this eternal misery! O, Laziness, mother of the arts and the noble virtues, be thou balsam for the pains of mankind!”

Languishing in a French prison in 1883, Paul Lafargue observed that a strange mania had lately gripped mankind. It seemed everyone had begun to worship what their God had damned. In their canonization of work — that vampire sucking the blood of modern society — they had forgotten His sublime example. Did He not toil for six days, then rest forever after? In his treatise The Right to Be Lazy, Lafargue intoned a prayer: “O, Laziness, have thou mercy upon this eternal misery! O, Laziness, mother of the arts and the noble virtues, be thou balsam for the pains of mankind!”

Enter the catatonic heroes of Albert Cossery’s Laziness in the Fertile Valley, exercising their right to do nothing. In a dilapidated villa in the Nile Delta, a family sleeps all day, rising only for meals. The cadaverous Galal, oldest of three brothers and friar of somnolence, staggers into the dining room in a dirty nightgown. Some say he is an artist. “Why are you awake?” he cries in abject horror. His uncle and brothers are gathered around a pot of lentils at the table. The youngest, Serag, secretly dreams with eyes half-closed of freeing himself from the familial inertia and doing the unthinkable — finding a job — perhaps in the factory being constructed nearby. But on his exploratory walks (he cannot help but fall asleep on the way), he finds the rusted heap forever unfinished. Their father, Old Hafez, never descends from his bedroom, yet hatches a controversial scheme to take a wife in his old age. Rafik, the middle son, must keep vigil during the siesta to kill the matchmaker conspiring to bring such an enemy of sleep into their den. Forced to stay awake, Rafik is fighting against the current in a dangerous river. “From time to time, in a supreme effort, he managed to free himself, he raised his head and breathed deeply,” Cossery writes. “Then, again, he found himself plunged into the depths of an annihilating sweetness. The waves of an immense, seductive sleep covered him.”

2.

“I should tell you that this setting, this household, they were my family.” On November 3, 1913, Albert Cossery was born in the Fagalla neighborhood of Cairo to a moderately wealthy Greek Orthodox family of Syro-Lebanese descent. “Certainly it’s romanticized,” Cossery said in an interview, “but my father didn’t work, and so he slept until noon. My brothers didn’t work either, nobody worked…. In truth, we were all sleeping. If someone heard a noise in the house, no one would move to go see what it was, even if there had been a thief.” Laziness, Cossery claimed, was the only thing his father Salim had taught him. Born at the end of the nineteenth century in a village near Homs in Syria, Salim immigrated to Egypt, where he acquired farmland and properties in the fertile lands of the Delta. While the fields grew cotton, dates, and watermelons, Salim read the newspaper and took naps. Albert sprouted under the wing of his grandfather, who lived with them in Fagalla. One day the grandfather decreed he would no longer leave his bedroom — not because he wasn’t able, but because he no longer felt like it. When Albert brought meals up to him, he would find him with a black cloth tied across his eyes, in order to obtain the perfect darkness. Sometimes, his grandfather forgot the blindfold was on his face.

Albert, the youngest, would awake alone at seven in the morning for school, first at the Jesuit Collège des Frères de la Salle, and later at the French Lycée. He began writing his first novel in French at age ten. At seventeen, he published a book of poems titled Les Morsures (“Bites”), which lifted heavily from his god, Baudelaire. “I am alone like a beautiful corpse,” he wrote, in an ode to Nuit. “The first night of the tomb.”

Cossery was sent to university in Paris in the 1930s, but claimed he studied nothing at all. Yet he had discovered that being a writer gave a respectable alibi to his inherited laziness. On his return to Cairo in 1938, he fell in with the Egyptian Surrealists — George Henein, Edmond Jabès, Anwar Kamil, and the painter Ramsès Younane, among others. Cossery joined their group Art et Liberté, and contributed short stories to their journal al-Tatawwur (“Evolution”). In 1938, observing the growing hostility of Europe’s totalitarian regimes to the artistic spirit, the Egyptian Surrealists penned a manifesto: “Long Live Degenerate Art!” André Breton in a letter to Henein from Paris wrote, “The imp of the perverse, as he deigns to appear to me, seems to have one wing here, the other in Egypt.”

At twenty-seven, Cossery published a collection of short stories, Les hommes oubliés de Dieu (“Men God Forgot”), which sketched the themes to which he would continuously return over the next sixty years: the misery of the poor, the absurdity of the all-powerful, the will to laugh — and to sleep through it all. In “The Postman Gets His Own Back,” a neighborhood wages war against those who would disturb its slumber. To safeguard his countrymen’s morning sleep, Radwan Aly, the poorest man in the world, fatally hurls his one and only piece of furniture, an earthenware chamberpot, out the window of his hovel at the noisy greengrocer hawking his wares. Even the police are dumbfounded at his sacrifice. Down the street, a washerman sleeps in his rusted laundromat, nary a soap bubble in sight. His head sinks into a basin of slumber, heavy as a stone slipping to the bottom of a pool. Then, “like a diver leaving a wave, the laundryman reappeared once more on the surface of life.” He brings dreams up to the surface, like sea-creatures.

At twenty-seven, Cossery published a collection of short stories, Les hommes oubliés de Dieu (“Men God Forgot”), which sketched the themes to which he would continuously return over the next sixty years: the misery of the poor, the absurdity of the all-powerful, the will to laugh — and to sleep through it all. In “The Postman Gets His Own Back,” a neighborhood wages war against those who would disturb its slumber. To safeguard his countrymen’s morning sleep, Radwan Aly, the poorest man in the world, fatally hurls his one and only piece of furniture, an earthenware chamberpot, out the window of his hovel at the noisy greengrocer hawking his wares. Even the police are dumbfounded at his sacrifice. Down the street, a washerman sleeps in his rusted laundromat, nary a soap bubble in sight. His head sinks into a basin of slumber, heavy as a stone slipping to the bottom of a pool. Then, “like a diver leaving a wave, the laundryman reappeared once more on the surface of life.” He brings dreams up to the surface, like sea-creatures.

During the war, Cossery joined the merchant marines and worked as chief steward on a liner called El Nil, ferrying passengers — many of whom fleeing the Nazis — on the route from Port Said to New York. It was uncharacteristic of him, this job, yet he would say it opened his world a bit wider. Cutting an elegant figure in his uniform, he seduced the prettiest of his passengers, and ignored the rest. According to an apocryphal tale, it was on a crossing of the Atlantic that Cossery met Lawrence Durrell. When they arrived in New York, the two were arrested on charges of espionage; Durrell protested that it was impossible, as Cossery spent all his time in bed. Though Durrell, in fact, would not visit the United States for the first time until 1968, it was through him that the first translation of Cossery’s stories reached an American readership. Dispatched by Durrell in Alexandria, Men God Forgot was published in Berkeley in 1946 by George Leite for Circle Editions. It was also through Durrell that Cossery met Henry Miller, who would become a lifelong champion. Miller so admired Cossery’s collection of stories, that “terrible breviary,” that when the translation failed to sell Miller bought up much of the stock — hundreds of copies — and peddled the book himself for decades. In Cairo in 1944, Cossery published his first novel, La maison de la mort certaine (“The House of Certain Death”) about the inhabitants of a derelict tenement building on the verge of collapse. “He is heralding the coming of a new dawn,” Henry Miller prophesied, “a mighty dawn from the Near, the Middle, and the Far East.” Cossery characteristically responded, “Perhaps that is exaggerated.”

During the war, Cossery joined the merchant marines and worked as chief steward on a liner called El Nil, ferrying passengers — many of whom fleeing the Nazis — on the route from Port Said to New York. It was uncharacteristic of him, this job, yet he would say it opened his world a bit wider. Cutting an elegant figure in his uniform, he seduced the prettiest of his passengers, and ignored the rest. According to an apocryphal tale, it was on a crossing of the Atlantic that Cossery met Lawrence Durrell. When they arrived in New York, the two were arrested on charges of espionage; Durrell protested that it was impossible, as Cossery spent all his time in bed. Though Durrell, in fact, would not visit the United States for the first time until 1968, it was through him that the first translation of Cossery’s stories reached an American readership. Dispatched by Durrell in Alexandria, Men God Forgot was published in Berkeley in 1946 by George Leite for Circle Editions. It was also through Durrell that Cossery met Henry Miller, who would become a lifelong champion. Miller so admired Cossery’s collection of stories, that “terrible breviary,” that when the translation failed to sell Miller bought up much of the stock — hundreds of copies — and peddled the book himself for decades. In Cairo in 1944, Cossery published his first novel, La maison de la mort certaine (“The House of Certain Death”) about the inhabitants of a derelict tenement building on the verge of collapse. “He is heralding the coming of a new dawn,” Henry Miller prophesied, “a mighty dawn from the Near, the Middle, and the Far East.” Cossery characteristically responded, “Perhaps that is exaggerated.”

As soon as the war ended, Albert Cossery left Cairo for Paris, where he would stay for thirty years without returning to Egypt. With a debonair look and an anarchist bent, he floated above the fray in a crowd of illustrious friends and admirers, such as Alberto Giacometti, Jean Genet, Tristan Tzara, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Raymond Queneau. At night, he went out dancing with Albert Camus, who introduced him to his French publisher, Edmund Charlot. Cossery lived in a flat in Montparnasse, but soon tired of the constant back-and-forth between his lodgings and the hotel in Saint-Germain-de-Prés where he brought girls. (Though he always maintained that women exhausted him, by the time he reached his eighties, Cossery was claiming more than 3,000 conquests.) In 1951, he moved permanently into the Hotel La Louisiane, that “grim old hostelry known to the bad boys of the Rue de Buci,” as Miller described it in Tropic of Cancer.

As soon as the war ended, Albert Cossery left Cairo for Paris, where he would stay for thirty years without returning to Egypt. With a debonair look and an anarchist bent, he floated above the fray in a crowd of illustrious friends and admirers, such as Alberto Giacometti, Jean Genet, Tristan Tzara, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Raymond Queneau. At night, he went out dancing with Albert Camus, who introduced him to his French publisher, Edmund Charlot. Cossery lived in a flat in Montparnasse, but soon tired of the constant back-and-forth between his lodgings and the hotel in Saint-Germain-de-Prés where he brought girls. (Though he always maintained that women exhausted him, by the time he reached his eighties, Cossery was claiming more than 3,000 conquests.) In 1951, he moved permanently into the Hotel La Louisiane, that “grim old hostelry known to the bad boys of the Rue de Buci,” as Miller described it in Tropic of Cancer.

One night in 1952, he met the actress Monique Chaumette over a bowl of peanuts; Cossery asked her to feed him some, she refused. Cossery gave her a copy of his latest novel, Les fainéants dans la vallée fertile, and she telephoned to say how beautiful she found it. Flattered, Cossery agreed to meet at his usual haunt, the Café de Flore. They shocked everyone by marrying in April of 1953. Yet married life did not agree with Cossery. She awoke too early. Her constant questioning as to what he would write next enervated him. And he refused to move from his austere hotel room. In a story from Men God Forgot, Cossery had described a hashish-addicted slacker named Mahmoud, who cannot shake the affections of the amorous Faiza. “He had wanted to teach her to sleep, to respect slumber, that brother to death which he himself loved so,” Cossery wrote, “but alas! she understood nothing of it.” Faiza asks Mahmoud how he can live this way. “‘How do I live? And what does that matter to you?” Mahmoud tersely replies. “Yes, I dream all the time.” Seven years later, Cossery and Chaumette divorced.

Impeccably dressed in a sport coat with a colored handkerchief in its pocket, Cossery would rise late each day, leaving the hotel only in the afternoons, perhaps to take in the sun and watch the girls of the Luxembourg gardens. He would sit for hours at the Flore doing nothing. To waiters who asked him if he was not bored, he replied: “I am never bored when I’m with Albert Cossery.” He wrote only when he had absolutely nothing better to do, producing a new novel roughly every decade. And yet, to exercise the right to laziness had its own miseries. Forever broke, he relied on his royalties and income from translations of his novels to survive. In the late forties, New Directions published the English translation of The House of Certain Death, and commissioned the novelist William Goyen to translate Les fainéants. Cossery’s letters to his American publisher James Laughlin reveal the underside of his elegant life of idleness: “My financial situation is totally desperate.” “The rate of the franc is 270 to the dollar.” “I am absolutely fucked.” “I am appealing to you to help me.” “Have you forgotten me?” “Send me a check as soon as possible.” “I am always, and I continue to be, in extreme misery.” Laughlin replied with detailed instructions on how to change money on the Parisian black market for a better rate. At a meeting at a Paris café in the late fifties, Cossery complained so bitterly about how badly his books had sold in the U.S. that Laughlin handed him money out of his wallet.

If he had little American readership, Cossery had even less of an Egyptian one. On a rare visit to Cairo in the nineties, his dogged Arabic translator Mahmud Qassim — who translated and published four of Cossery’s novels — insisted on “a meeting of two monuments.” He dragged Cossery to meet Naguib Mahfouz. The Nobel Laureate had no idea who he was. Although Cossery claimed to have always carried Egypt inside him, to Egyptians — those who knew of him — he had deserted it. As Qassim said in an interview, “They don’t forgive him for having abandoned Arabic and emigrated to another language.” Worse, the other language was French, the purview of a marginalized elite. Like a dreamer in a cave, Cossery had missed the revolution of 1952, which had branded French, once the language of bourgeois aspirations, as aristocratic and elitist. Moreover, Cossery admitted that after years in Paris, he had forgotten much of his Arabic. Beyond the language barrier, his celebration of laziness and his romanticization of Egypt’s lowlife held little resonance for a readership actively trying to live in, and improve, the country, while often locked in battle against the state. While fellow writers such as Ahmed Fouad Negm and Abd al-Hakim Qasim were thrown in prison, or forced into exile like Jabès and Henein, Cossery sat idly at the Flore.

3.

At the beginning of Cossery’s 1975 novel A Splendid Conspiracy, Teymour, recently returned to Egypt with a fake engineering diploma bought after years of “studying” in Europe, sits dejectedly at a café newly renamed “The Awakening.” He contemplates a statue in the center of the nearby square. Known as The Awakening of the Nation, it depicts a peasant woman with arms outstretched, “as if to denounce the torpor of the residents.” In the scene, Cossery conjures the Nahdat Misr, the granite sculpture of “The Awakening of Egypt” that still stands near Cairo’s Giza Zoo. Completed in 1928 by the renowned sculptor Mahmud Mukhtar, it portrays a peasant throwing back her veil and rousing a sleeping sphinx. The two symbols, of a storied past and a vital present, face east to a new dawn. The sculpture commemorated the events of 1919, in which hundreds of thousands of Egyptians across the country — students, peasants, civil servants, and the elite — had joined together in civil disobedience to reject the British occupation. Cossery was nine when the nation gained nominal independence in 1922. Everywhere it was said that, having fallen behind the times, Egypt, and the greater Arab world, was at last awakening — or must awake — from its long slumber into modernity. It was this obsession with the awakening that Tawfiq al-Hakim, a writer Cossery much admired, chose to play upon by reanimating the three-hundred-year-old sleepers from the Quran.

At the beginning of Cossery’s 1975 novel A Splendid Conspiracy, Teymour, recently returned to Egypt with a fake engineering diploma bought after years of “studying” in Europe, sits dejectedly at a café newly renamed “The Awakening.” He contemplates a statue in the center of the nearby square. Known as The Awakening of the Nation, it depicts a peasant woman with arms outstretched, “as if to denounce the torpor of the residents.” In the scene, Cossery conjures the Nahdat Misr, the granite sculpture of “The Awakening of Egypt” that still stands near Cairo’s Giza Zoo. Completed in 1928 by the renowned sculptor Mahmud Mukhtar, it portrays a peasant throwing back her veil and rousing a sleeping sphinx. The two symbols, of a storied past and a vital present, face east to a new dawn. The sculpture commemorated the events of 1919, in which hundreds of thousands of Egyptians across the country — students, peasants, civil servants, and the elite — had joined together in civil disobedience to reject the British occupation. Cossery was nine when the nation gained nominal independence in 1922. Everywhere it was said that, having fallen behind the times, Egypt, and the greater Arab world, was at last awakening — or must awake — from its long slumber into modernity. It was this obsession with the awakening that Tawfiq al-Hakim, a writer Cossery much admired, chose to play upon by reanimating the three-hundred-year-old sleepers from the Quran.

The awakening had at times seemed alloyed with the residue of a strange dream. To transform it into a profit-generating subsidiary of the Empire, the British had introduced new technologies to Egypt such as the railway, the telegraph, and electrical networks. In the early years of the development of the railway, until a steady supply of coal was secured, Egyptian trains, as well as Nile steamers, were occasionally fueled by the mummies frequently unearthed in the valleys. The embalming potions, it turned out, made for first-rate burning materials. A medical journal in 1859 reported: “It is a curious fact that the bodies of the most enlightened nation in its time, many years ago, are now made to aid in getting up steam in the present fast age.” Mark Twain, on his trip to Egypt, joked, “Sometimes one hears the profane engineer call out pettishly, ‘D–n these plebeians, they don’t burn worth a cent— pass out a King!’” The past, no longer able to rest in peace, collided with the effort to modernize.

The stereotype of Oriental indolence, which Cossery pushes to the absurd in Laziness in the Fertile Valley, was built into the very infrastructure of modernity itself. According to Egypt’s retired colonial governor Lord Cromer in 1908, the typical Egyptian was “devoid of energy and initiative, stagnant in mind, wanting in curiosity about matters which are new to him, careless of waste of time, and patient under suffering.” Egyptian laziness, in turn, determined railway timetables and management structures, and became a durable component of the system. It was thought that the Orient did not require the same standards of efficiency or reliability as the Occident, and so a different approximation of punctuality was enforced for British and Egyptian trains. As “Arab time” became institutionalized, the stereotype of idleness became a self-fulfilling prophecy: Egyptians would languish for hours in stations waiting for the capricious train.

If the trains reified laziness, it was the arrival of electricity that gave a jolt to the spirit. For some, electricity took the possibility of an “awakening” out of the realm of metaphor and into that of hard science, as it was understood at the time. In 1905, as discoveries were being made in the field of electromagnetism by Einstein and others, the journal Al-Sahafa ran an article on the phenomenon of tanwim magnatisi (“magnetic sleep inducement”), and the ways in which the electromagnetic current accounts for different flows of energy between the earth and the celestial bodies, and inside the human body and mind. It was followed by an article, “Are We Alive or Dead?” which argued that Egypt was still under a global electro-magnetically induced sleep, from which the West had been the first to awaken. Alert, the West had come to oppress the East. The writer then wondered when Egypt would rise from its own trance. During the rebellious months of 1919, riots targeted the electric streetlights, that technology which tames the night and ruins sleep. The British had constantly pointed to the technological advances they had introduced to Egypt as benefits of colonial rule. As streets fell into darkness, artificial illumination became a political symbol. Streetlamps were guarded by the police.

4.

With the rousing of the nation had come the introduction, not unanimously welcomed, of the clock. (Perversely, though God Himself has idled ever since His six days’ work, the first mechanical clocks were used by 14th century Benedictine monks hoping to keep their prayers on a rigorous schedule.) In 1830, Muhammad Ali Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt, gave France the majestic obelisk that now stands in the Place de la Concorde in exchange for a clock, which some say never even worked. During the occupation, British Time was introduced into Egypt, with Egyptian “slave clocks” taking their orders from the Greenwich observatory. For Egypt to be profitable, it was essential that it function on a synchronized schedule. In the 1870s, the British began to impose the shift from the age-old lunar Hijri calendar to the solar Gregorian calendar. (It’s April 45th, declared an advertisement, selling a wall calendar, in one Cairo newspaper.) Yet even after the confusion subsided, Egyptians could never fully accept the imposition of European timekeeping. Clock time was not neutral, or apolitical, or natural, as it might have seemed to a Parisian glancing at his watch. The memory of the lunar calendar, something traditional, authentic, and now lost, inflamed the nationalist spirit.

Although it had been introduced in order to further imperialist aims, the fixation on clock-time soon led to a popular obsession with “the value of time.” Articles began appearing in the press that gently admonished the lazy Egyptian to “remember that time is money.” Hassan al-Banna, the son of a watchmaker and the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, took issue with this equation, writing in a letter from the 1920s that time is even more precious than gold. Religious clerics made efforts to embed punctuality into the system of Islamic ethics. Though the railroads literally ran on laziness, managers introduced harsh penalties for its workers’ indolence: half a day’s wages would be withheld for five minutes’ lateness to work. In Fagalla, catty neighbors gossiped about the Cossery family’s idleness.

Against this monetization of time Albert Cossery stood firm. As monuments cheering Egypt’s progress went up, Cossery chose in his novels to reveal the deep bedrock of sloth underlying it all. Sleep nibbles everything, he wrote, “like the teeth of invisible rats.” In Laziness, retired civil servants grow moldy on the outskirts of the city, while in the center, workers in dusty corporate offices are asleep. There is the idleness that stands against work, and an idleness within work. There is the private and the public laziness. Abou Zeid, the peanut seller, naps in his empty shop; the factory that would threaten the countryside, eternally under construction, is a stage-set for Serag’s torpor. In Cossery’s novels, the only one who works hard is the prostitute. And yet, laziness goes beyond doing nothing. “The more you are idle, the more you have time to reflect,” Cossery said in an interview in his eighties. Laziness is a critical position by which to judge the world — a perspective the salaried clock-puncher lacks. “The Orient is more philosophical than the Occident,” Cossery declared. “Everyone’s a philosopher because they wait, they think. Everyone in the West is after money. I have lived my life minute by minute,” though it had meant dire financial straits. With idleness comes godliness. Away from the hourglass of the city, Cossery said, “the further one goes toward the South, toward the desert, there are more prophets, more magi — more people who have reflected on the world.” After his death, the long-sleeping Epimenides was honored as a god in Crete.

5.

In a cartoon published in 1921 in the journal al-Kashkul, the sculptor Mukhtar rides on top of a sphinx, with an alarm clock in each hand. “Did the alarm clock awake you to behold the Awakening statue?” asks a voice in the picture. “It gave me a headache,” another voice replies, “all I see in the Awakening is noise, commotion, and discord.” In A Splendid Conspiracy, as Teymour contemplates the statue of the Awakening, he observes, “she seemed to be lamenting the fact that she had been woken up to see this abomination.” In Laziness, through the character of Serag, Cossery poses the question whether Egypt should slip back into its slumber, given the dissonance brought about by the attempt to catch up with modernity. Serag’s name means “lamp,” a beacon (or a nuisance) in the darkness of the family home. When he threatens to leave for the city to find work, Rafik attempts to rid him of his illusions. “Do you know, my dear Serag, that there are countries where men get up at four o’clock in the morning to work in the mines?” “Mines!” says Serag, “It isn’t true; you want to frighten me.” “I know men better than you do,” Rafik replies. “They won’t wait long, I tell you, to spoil this fertile valley and turn it into a hell. That’s what they call progress. You’ve never heard that word? Well, when a man talks to you about progress, you can be sure that he wants to subjugate you.”

As Teymour sits in the Café Awakening, a noisy caravan passes before him. It’s Wataniya, the monstrous madame of the local brothel, showing off her coterie of hookers. Cossery’s choice of name is striking, for the word “wataniya” means “nationalism.” If the peasant woman of Mukhtar’s Awakening statue had a name, she too would be Wataniya. The name plays on the tradition of metonymy in earlier Egyptian nationalist novels — such as Husayn Haykal’s Zaynab, widely considered to be the first Egyptian novel, and al-Hakim’s The Return of the Spirit, about the days leading up to the 1919 revolution — in which the main female character is used to represent the nation. And yet, in Cossery’s version, the notables of the city keep disappearing into Wataniya’s fatal brothel. As landowners and bureaucrats are mysteriously killed, the whore “Nationalism” emerges as a deadly trap. Better to sleep than risk her caresses.

As Teymour sits in the Café Awakening, a noisy caravan passes before him. It’s Wataniya, the monstrous madame of the local brothel, showing off her coterie of hookers. Cossery’s choice of name is striking, for the word “wataniya” means “nationalism.” If the peasant woman of Mukhtar’s Awakening statue had a name, she too would be Wataniya. The name plays on the tradition of metonymy in earlier Egyptian nationalist novels — such as Husayn Haykal’s Zaynab, widely considered to be the first Egyptian novel, and al-Hakim’s The Return of the Spirit, about the days leading up to the 1919 revolution — in which the main female character is used to represent the nation. And yet, in Cossery’s version, the notables of the city keep disappearing into Wataniya’s fatal brothel. As landowners and bureaucrats are mysteriously killed, the whore “Nationalism” emerges as a deadly trap. Better to sleep than risk her caresses.

Though the people might slave for the flourishing of this new imagined “Egypt,” and sacrifice themselves to her, the entrenched powers did not want the nationalist spirit to get too far ahead. When Cossery left for Paris in 1945, the year he wrote Laziness, Cairo was in the midst of what would be nostalgically remembered as its gilded age. Money had flowed in from Europe during the two wars, enriching the aristocratic elite. Cinemas, opera houses and villas shot up along the boulevards, in styles that mixed Art Deco with Arabesque and Neo-Pharaonic, a craze that had struck Egypt since the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in the twenties. Armenian studio photographers captured pasha’s wives in the latest fashions from Paris. A cast of glamorous exiles sipped whiskey at the Gezira Sporting Club, while Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek convened at the foot of the Pyramids. In 1936, King Farouk took the reins of power from his father Fuad, who, along with Farouk’s mother, Queen Nazli, had kept Breton’s imp of the perverse well-fed. While Nazli performed nighttime séances, Fuad slept with a Circassian servant girl curled up on a rare Chinese carpet at the foot of his bed. Unbounded by means or appetite, the fattened Farouk rolled between his four palaces and yachts with his chief confidante, an Italian plumber, by his side.

Farouk was at best a puppet of the British: much of Egypt was foreign-owned, including its entire tramway and electrical networks. Under his reign, the veneer of “progress” belied the worsening misery of the poor. While the rich literary culture that first published Cossery and Jabès flourished, only one in seven Egyptians could read. Child labor, sixteen-hour workdays, and corruption were common. City sharks swindled the rural poor. As public health improved, the population exploded — Cairo began to grow so fast that it lost control of its own slums. In a short story from the thirties, Cossery described the march of the city lights across the Egyptian countryside: “Strange harlot’s body: it spread in all directions, always venal, always interested. And the countryside fled before it, rapid and monotonous. The city chased it without respite. Accursed countryside, which went off to vomit its distress at the edges of the poorer quarters.”

In their villa on the outskirts, Serag’s father scares him from looking for a job in the city by telling him that the government has arrested rebels. “But was he a rebel? Was his desire to look for work and to mingle with working men a revolutionary act?” Cossery writes. “Serag didn’t understand why his love of an active life should be considered by the government as an attempt at revolt against the established laws.” In 1945 alone, thousands of workers were arrested during trade union strikes and government crackdowns. It was too dangerous to hope for better labor conditions, or to challenge the monarchy held up by strings. Instead, as Cossery wrote in Laziness, “the country slept in its snare.”

6.

On July 2, 1952, a few months before its publication date, a case of the New Directions edition of Goyen’s translation of Les fainéants, then titled The Lazy Ones, was lost or “hijacked” off a truck somewhere in New England. On the 23rd of that month, a coalition of young Egyptian army officers led by Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew the regime in a coup d’état. With Farouk exiled, Nasser introduced socialist reforms, seized foreign businesses, and redistributed Egyptian wealth. “Arab nationalism is fully awakened to its new destiny,” Nasser declared in 1956, as he pushed for the nationalization of the Suez Canal. And yet, as workers were killed by the police and intellectuals imprisoned, it became clear to many that the awakening had only replaced one bad dream with another. In Cossery’s 1964 satire The Jokers, a mad old lady has a dream about her son’s friend Heykal (perhaps named after the author of Zaynab, an opposition leader). A practical joker and an anti-authoritarian agitator, Heykal and his comrades set out to topple the regime by postering the city with embarrassingly effusive pro-government propaganda. In the dream, Heykal is riding on a white horse and slaying a dragon. Yet after each blow, the dragon is reborn and refuses to die. “And you, prince, you laughed and laughed,” recounts the woman. “And I knew why you laughed. Deep down, you didn’t want to kill the dragon; the dragon entertained you too much for you to want it dead.”

On July 2, 1952, a few months before its publication date, a case of the New Directions edition of Goyen’s translation of Les fainéants, then titled The Lazy Ones, was lost or “hijacked” off a truck somewhere in New England. On the 23rd of that month, a coalition of young Egyptian army officers led by Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew the regime in a coup d’état. With Farouk exiled, Nasser introduced socialist reforms, seized foreign businesses, and redistributed Egyptian wealth. “Arab nationalism is fully awakened to its new destiny,” Nasser declared in 1956, as he pushed for the nationalization of the Suez Canal. And yet, as workers were killed by the police and intellectuals imprisoned, it became clear to many that the awakening had only replaced one bad dream with another. In Cossery’s 1964 satire The Jokers, a mad old lady has a dream about her son’s friend Heykal (perhaps named after the author of Zaynab, an opposition leader). A practical joker and an anti-authoritarian agitator, Heykal and his comrades set out to topple the regime by postering the city with embarrassingly effusive pro-government propaganda. In the dream, Heykal is riding on a white horse and slaying a dragon. Yet after each blow, the dragon is reborn and refuses to die. “And you, prince, you laughed and laughed,” recounts the woman. “And I knew why you laughed. Deep down, you didn’t want to kill the dragon; the dragon entertained you too much for you to want it dead.”

Revolution is futile, yet Cossery’s heroes do not mind. Were it to succeed, it would leave them with no one to laugh at. Though he had highly politicized friends, such as the Egyptian communist Henri Curiel, Cossery himself never joined any political parties. “I hate politics,” he said in an interview, “but I cannot write a sentence which is not a rebellion.” He understood that a mode of living, expressed in his novels and in his daily life, could be revolutionary. In conversation with Michel Mitrani, his interviewer, exasperated, remarked, “This dormancy, it’s totally engulfing!” “But it’s a symbol,” Cossery replied, “of refusing a certain world.” Whenever he was asked why he writes, he would reply, “So someone who just read me decides not to go to work.” In Laziness, as Rafik attempts to dissuade Serag from undertaking such a thing, the slumberous Galal enters the scene. “Why are you awake!” he groans. His brother explains their predicament. “God help him,” murmurs Galal. “God is with the lazy,” Rafik declares. “He has nothing to do with the vampires who work.” “You’re right,” echoes Galal. “Where can I sit down?”

7.

Goyen’s translation of Laziness in the Fertile Valley has been in a deep sleep for sixty years. At various intervals, the idea of rousing it was debated, but editors feared it had gone musty. In Cairo in early 2011, I had brought a few of Albert Cossery’s books with me. Egypt was in a state of euphoria: by overthrowing Hosni Mubarak’s thirty-year dictatorship, it had done what had seemed impossible. Reading his novels amid the exhilaration of the uprising, Cossery seemed irrelevant or, happily, wrong. Yet not long after, following the elections that installed the Muslim Brotherhood in power, the new rulers began to instate their vision for Egypt’s future. They granted themselves sweeping powers, restricted civil liberties, and imprisoned dissenters, in the midst of economic crisis and electrical blackouts. They called their plan — unsurprisingly — the Nahda, or Awakening Project. But after the Egyptian army

stepped in to depose the new president, it was against Mukhtar’s statue of the Awakening that his supporters turned their anger. They spray painted slogans and papered the failed leader’s portrait over the faces of the peasant and the sphinx. In the military’s attempt to disperse the demonstrators at the foot of the Awakening and elsewhere, over a thousand people were killed.

In an early short story, Cossery had imagined a battle between the city’s streetlights and the moon. “The street was deserted,” he wrote. “He saw only the poor street lamp, which was trying to show some signs of life in spite of the intense light of the moon. It looked like a human being, a humble person crushed down by the luxury and power of a tyrannical force against which it could do nothing. In this drama of the street, the moon personified the privileged minority in this world, and under its brilliance the poor street lamps died in their thousands.” Rather than imagining the moon as a benevolent orb, friend of lovers and poets, shining above the streetlamp—that artificial, politicized star—the moon is the despotic elite. And yet what remains if we, the lazy ones, have an enemy even in the moon?

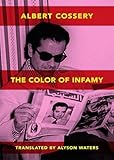

We could shut our eyes against the lights. Sleep is refusal, a protest, a weapon. “I am always indignant,” said Cossery to an interviewer. “About what?” “Everything that I see.” In his first novel, The House of Certain Death, the young Cossery had ended on a note of high prophecy: “The future is full of outcries; the future is full of revolt. How to confine this swelling river that will submerge entire cities?” And yet, by his last novel, The Colors of Infamy, published in 1999, he writes of the hero, a charming pickpocket, “Ossama’s objective was not to have a bank account (the most dishonorable thing of all), but merely to survive in a society ruled by crooks, without waiting for the revolution, which was hypothetical and continually being put off until tomorrow.” The future is full of revolution; the revolution is forever in the future. The two possibilities cancel each other out, and what are we left with? Cossery’s philosophy of idleness emerges as a via negativa, a political mysticism of its own. All that’s left is to dive into the annihilating sweetness.

We could shut our eyes against the lights. Sleep is refusal, a protest, a weapon. “I am always indignant,” said Cossery to an interviewer. “About what?” “Everything that I see.” In his first novel, The House of Certain Death, the young Cossery had ended on a note of high prophecy: “The future is full of outcries; the future is full of revolt. How to confine this swelling river that will submerge entire cities?” And yet, by his last novel, The Colors of Infamy, published in 1999, he writes of the hero, a charming pickpocket, “Ossama’s objective was not to have a bank account (the most dishonorable thing of all), but merely to survive in a society ruled by crooks, without waiting for the revolution, which was hypothetical and continually being put off until tomorrow.” The future is full of revolution; the revolution is forever in the future. The two possibilities cancel each other out, and what are we left with? Cossery’s philosophy of idleness emerges as a via negativa, a political mysticism of its own. All that’s left is to dive into the annihilating sweetness.

By the time he wrote The Colors of Infamy, Albert Cossery had lost his voice. Forced to undergo a laryngectomy after years of smoking, he could only hiss. Yet he preserved his routine as ever. He escaped the hospital to go to a café, wearing the ward pajamas. Pushed in a wheelchair by a beautiful blonde, he was as striking a sight as ever. In place of speaking, Cossery would write on notecards in a shaky yet elegant hand, a mischievous look in his eyes. “The loss of my voice gives me relief because I don’t have to respond to imbeciles.” “To look at pretty girls, there is no need to speak.” “I have nothing in common with the world.” “I am nothing except what is contained in my books.” “Read them, and you will know who I am. All I have to say is in my books.” In 2008, Cossery was made a Chevalier in the Légion d’honneur by President Sarkozy. He refused to accept.

Tawfiq al-Hakim’s three-hundred-year-old saints, having found they cannot live in this new world, retreat back into their cave. As they lay dying, delirious, they wonder whether it was all a dream. And whose dream was it — time’s dream, or their own? “Time is dreaming us,” one says to the other. “We dream Time,” the other replies. “Didn’t we live three hundred years in one night? I’m tired from the dream.” Time it stopped. On June 22, 2008, at ninety-four, Albert Cossery died in the room at the Hotel Louisiane where he had resided for sixty years.

“Men are asleep,” he wrote. “Time takes on a new dignity, relieved of men and their eternal wrangles.” The moon continues to do as it pleases: ostentation one night, austerity a few weeks later. But the sun, sinking its heavy head into the horizon every evening, is on our side.

Author Note: This piece is indebted to On Barak for his work on the history of timekeeping in Egypt. To learn more, see his new book On Time: Technology and Temporality in Modern Egypt.