1.

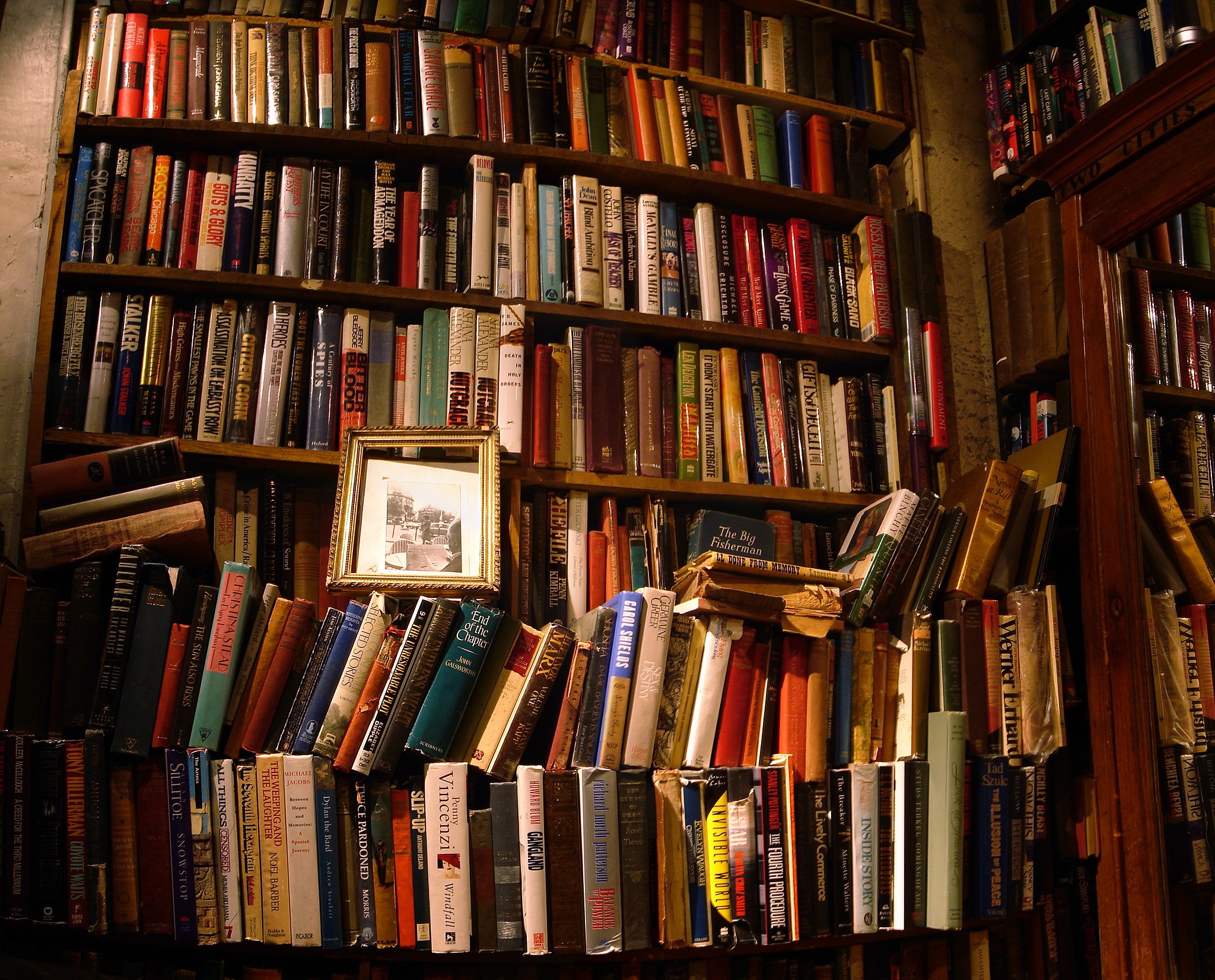

There is perhaps no more fitting summer job for a writer than processing books in the basement of a university library. To get up before the real heat of the day begins and descend into the air-conditioned cool of the dimly-lit basement archives is a particular kind of atmospheric trick, but emerging after a full day’s work into the thick evening is even better, since it mimics the way writers feel when they get up from a long grapple with a manuscript; your eyes are bleary, your head is half-dazed, and the hot summer night feels overly sharp, hyper-real, cluttered with shouts and sirens.

(I highly recommend an archiving job as a remedy for the effects of writer’s block, since it’s easy enough to pretend that a pile of close reading is a substitute for your own literary production. Your verbal overload is no less intense for being totally vicarious.)

All of this describes the job I worked last summer, in the rare books section of a local university library. I was assigned to a basement room nicknamed “the cage,” because most of the shelving was set off behind a wall of wire mesh, accessible only by a carefully guarded key. I did my work at a small desk in the corner, and when I wanted to enter the cage I had to ask for this key, and return it to its appointed hook straightaway when I was done.

The project that I was hired to work on is somewhat difficult to describe. Sometime in the early aughts, a famous bookstore in New York—I can’t tell you which one, on conditions of job-related secrecy—closed its doors forever, at which point several wealthy patrons banded together to buy its entire inventory (distressed periodicals and all) and hand said inventory over to a local university library. This inventory consisted of thousands upon thousands of volumes: some rare, some middling, some eminently forgettable. They had early editions of Finnegans Wake, nestled next to paperback Modern Library editions of the collected works of Thackeray, propped up against a stack of 25 cent magazines for teen movie lovers of the 1950s.

The project that I was hired to work on is somewhat difficult to describe. Sometime in the early aughts, a famous bookstore in New York—I can’t tell you which one, on conditions of job-related secrecy—closed its doors forever, at which point several wealthy patrons banded together to buy its entire inventory (distressed periodicals and all) and hand said inventory over to a local university library. This inventory consisted of thousands upon thousands of volumes: some rare, some middling, some eminently forgettable. They had early editions of Finnegans Wake, nestled next to paperback Modern Library editions of the collected works of Thackeray, propped up against a stack of 25 cent magazines for teen movie lovers of the 1950s.

I am not a rare books specialist; I am not capable of making fine distinctions. I do not know a first edition unless it is clearly marked in the front of the book, preferably in large type, all capitals. Thus my job consisted only of logging the books, regardless of content or merit, into the computer system: name, title, ISBN, and relative condition.

There have been moments of excitement. I have shelved books from the personal libraries of Anaïs Nin and Joseph Mitchell. I have learned terms which include, but are by no means limited to: bastard title page, bumped corners, colophon, ex libris, flyleaf, foxing, worn boards, and gutter tear. I have held William Gaddis first editions and signed versions of nearly every title in Joyce Carol Oates’s massive oeuvre.

But the actual function of my day was repetitive, nearly robotic.

Name, Title, ISBN

worn board edges

gutter tear in front flyleaf, board corners slightly bumped,

dj (short for “dust jacket”) worn

owner’s signature on front flyleaf “(illegible), Chicago, 1923”

inscription on front flyeaf: “To Brenda, for the memories, Cape Cod, 1932”

A New Yorker cartoon, featuring a man pushing a massive cube up a featureless hill, was taped to the wall above my supervisor’s desk. The caption: Extreme Sisyphus.

2.

Common themes in books, 19th to early-20th century:

Detailed author portraits on the title page, covered in thin, almost tissue-like paper (to prevent blotting?)

Inexplicably small, but also thick, multi-volume editions of the novels of Sir Walter Scott, of which multiple volumes are missing

Inscriptions from fathers and uncles in said novels, in loopy, almost illegible cursive, along the lines of: may this add to your education

3.

When one thinks of libraries in literature, the most famous reference point has to be Borges‘s The Library of Babel, in which the Argentine writer (in a joking mood) conceived of an infinite library, composed of a series of hexagonal rooms, and posited (half-ironically) that the library was a stand-in for the perfect divine creation: “the universe, with its elegant endowment of shelves, of enigmatical volumes, of inexhaustible stairways for the traveler and latrines for the seated librarian, can only be the work of a god.”

Often, during my summer in the archives, I would reflect on the fact that all my work was only the reconstruction or (to be more accurate) weird vivisection of an already existing bookstore. The books I catalogued came to me in numbered trays, with each section number corresponding to a section of the now-departed bookstore, and on days when my mind really wandered—which was a higher percentage than I would have admitted to my immediate superiors—I considered the possibility of reconstructing the bookstore in my head, using the section numbers and the books I’d processed, recreating a sort of bookstore-of-the-mind.

Usually, however, I was interrupted from my reverie by one or another common typo:

Worn bards, utter tear.

And, even if I managed to keep my mental concentration long enough to maintain one section of this library-of-the-mind, the idea of trying to juggle multiple sections ended up being too much, and I was forced to give up the whole project, having only completed one of Borges’s hexagons.

Which reminds me of another quote from The Library of Babel:

“When it was proclaimed that the Library contained all books, the first impression was one of extravagant happiness. All men felt themselves to be the masters of an intact and secret treasure.”

By the time I arrived at my archiving job, the project had already been going for nearly seven years, and over half of the books had been catalogued. Of course, each volume would still need to be judged and sorted by minds more discerning than mine, which meant that, like many projects conceived at the university level, it might last for much longer than the scope of ordinary human patience.

There is something strange about doing a job that you will never see finished, like Kafka’s Great Wall of China:

“Five hundred meters could be completed in something like five years, by which time naturally the supervisors were as a rule too exhausted and had lost all faith in themselves, in the building, and in the world.”

4.

Common themes in books, early- to mid-20th century:

Books of obscure poetry inscribed by nuns

Books published under the auspices and regulations of the U.S. Military

Mass-market book plates with bucolic scenes: cows, dogs, and/or roosters

5.

As a fiction writer, I am perhaps unusually interested in what makes a book last. Much of this I ascribe to pure ego. During my stint in the university library, I happened to come across the great English critic Cyril Connolly’s Enemies of Promise, which is a very odd and very vain book; it begins as an investigation of this very question, “why does a book last” (Is it prose style? Content? Political conviction?) only to devolve into a self-pitying investigation of why Cyril Connolly himself couldn’t write such a lasting book.

As a fiction writer, I am perhaps unusually interested in what makes a book last. Much of this I ascribe to pure ego. During my stint in the university library, I happened to come across the great English critic Cyril Connolly’s Enemies of Promise, which is a very odd and very vain book; it begins as an investigation of this very question, “why does a book last” (Is it prose style? Content? Political conviction?) only to devolve into a self-pitying investigation of why Cyril Connolly himself couldn’t write such a lasting book.

I assume that most readers of books do not engage in this sort of absurd behavior. Fiction writers have such high regard for themselves that they can’t see why they shouldn’t be immortal. Keeping their work in print is the next best thing available.

(An addendum: during my work in the archives I logged several thousand copies of Horizon, the British literary magazine which Connolly edited. Of the many names inside its covers, I recognized two.)

Still, if one puts pure vanity aside for a moment, the process by which a book survives more than a century is a fascinating thing. When I held a copy of Wilkie Collins’s 1868 novel The Moonstone, or an early American edition of Wuthering Heights, I’d sometimes reflect on the many deaths the book had to avoid on its way to me. It had to be bought, first of all, and not left to linger on a bookstore shelf, and later pulped—or, as is sometimes the case, burned. Then someone had to keep it after the first read, keep the bindings dry, move it from house to house, and later, after that person died, the book had to be inherited, or else sold, instead of thrown away; at the very least it had to be packed in such a way that the book block didn’t warp and the pages didn’t go moldy: all the little deaths to which a hardbound book is vulnerable.

Still, if one puts pure vanity aside for a moment, the process by which a book survives more than a century is a fascinating thing. When I held a copy of Wilkie Collins’s 1868 novel The Moonstone, or an early American edition of Wuthering Heights, I’d sometimes reflect on the many deaths the book had to avoid on its way to me. It had to be bought, first of all, and not left to linger on a bookstore shelf, and later pulped—or, as is sometimes the case, burned. Then someone had to keep it after the first read, keep the bindings dry, move it from house to house, and later, after that person died, the book had to be inherited, or else sold, instead of thrown away; at the very least it had to be packed in such a way that the book block didn’t warp and the pages didn’t go moldy: all the little deaths to which a hardbound book is vulnerable.

There is a certain kind of immortality to a passed-down book—the sense of having outlived many human lives.

So what makes a book last—not just in the minds of critics and readers, but also as a physical object? What’s essential here is a combination of initial popularity, physical hardiness, and a sterling reputation. There were more copies of The Moonstone in circulation than a host of other Victorian mysteries, so it had a good start, and the hardback edition I handled one summer morning seemed to have lasted pretty well, but nobody reads Wilkie Collins anymore (my apologies, Moonstone aficionados, bless your cosseted Victorian hearts), and so I have my doubts about what will happen when the library higher-ups finally handle the archive’s copy.

The local university library can’t possibly hold all of the books I archived, much less the whole of the departed bookstore; many of the books will be sold at sidewalk sales, to readers much less scrupulous about their storage.

Some, I’m sure, will simply be pulped—or burned.

6.

Common themes in books, mid- to late- 20th century:

Signed copies of books which immediately go out of print, their authors forgotten

Male poets with sideburns who write poems about driving

Poets of any gender with sad, searching eyes who write about cancer

Long biographical notes which expose their authors’ desperate search for respect

7.

There’s no keeping ego out of the conversation entirely, though. What fiction writer could work for a whole summer handling old novels without wondering about the fate of any book he or she might manage to publish in their lifetime? Based on even the slightest research, the percentages are bad. Is the work you’re producing destined to be recycled—or, now that everyone’s crowing about e-books, erased from the world’s collective hard-drive?

(As if it wasn’t worrying enough to get published in the first place.)

Or, if you’re the type to raise your concerns to the highest power, you can occupy yourself with a larger existential question: why, once you’ve witnessed a pile of words beyond human comprehension—when you’ve personally catalogued more books in a single day than it would be possible for you to read in an entire year—would you ever go on writing novels in the first place?

Forget about the death of the novel, for a moment—that old saw—and consider, instead, its terrifying, zombie-like nature. Old novels never die; they walk among us, tattered and moldy, neither living nor totally destroyed, giving off an offensive fungal stink that can best be described as a cross between rancid dust and damp feet.

Worse still, these zombie books have a way of infecting the living volumes which sit next to them; for every book is only a year’s neglect away from turning undead itself, a victim of time and circumstance, one more body for the undead legions.

From The Library of Babel: “The certitude that everything has been written negates us or turns us into phantoms.”

8.

Common trends in books, early-21st century:

Desperation

Confusion

Total lack of clarity

9.

Despite all overarching existential concerns, I usually left my job at the archive feeling exhilarated. Part of this was just a matter of getting off work; like I said before, the job itself was rote and methodical, an amazing combination of repetitive stress and screen fatigue. Just being able to walk free in the summer evening was a glorious feeling.

But, during the best —when I could leaf through a whole stack of 19th-century French poetry in translation, or the collected prose of William Carlos Williams, or all the books Joseph Mitchell owned concerning Gypsies—I experienced a more than bodily thrill at having run my eyes over so many odd and obscure titles, so many volumes that had survived years and chance to arrive in my hands—a feeling that was only increased by the possibility of the books’ destruction, despite my careful cataloguing. I was there to log books, not to save them.

It was a feeling I can only compare to the narrator of Bohumil Hrabal’s Too Loud a Solitude, a man whose work consists of pulping books into a paper compactor, which he describes as “holy work,” and whose responses to the avalanche of words echo my own:

It was a feeling I can only compare to the narrator of Bohumil Hrabal’s Too Loud a Solitude, a man whose work consists of pulping books into a paper compactor, which he describes as “holy work,” and whose responses to the avalanche of words echo my own:

…inquisitors burn books in vain. If a book has anything to say, it burns with a quiet laugh, because any book worth its salt points up and out of itself… When my eye lands on a real book and looks past the printed word, what it sees is disembodied thoughts flying through the air, gliding on air, living off air, because in the end everything is air…

At times it felt as if I was swimming in sentences, with the sense of Heraclitus, dipping into the river over and over and coming up with new books, new iterations of language, as if by taking the job I’d turned on a continuous flow of literature. Here, individual work seemed frankly meaningless, reminding me that intertextuality is not some new thing—for language is always in conversation with itself.

Thus I spent my summer vacation: building a library of the mind.

Image Credit: Wikimedia/Alexandre Duret-Lutz from Paris, France