1.

I don’t think I ever quite knew myself until I read Seamus Heaney. I can’t remember exactly which of his poems I read first, but that’s not important. What is important is what his poems did to me. When I encountered “Blackberry Picking,” I first felt the full force of what a poem can do. The poem describes picking blackberries in the spring and hoarding them in a tub in the barn, then discovering that they have begun to rot, ending with the lines “It wasn’t fair / That all the lovely canfuls smelt of rot. / Each year I’d hoped they’d keep, knew they would not.” The poem hit me somewhere right at the base of my ribs. It created an actual physical sensation. When I was a kid, I was always catching small animals, usually crickets and frogs, and keeping them in coffee cans, then forgetting about them for days, only to return and find their corpses. I remember the mingled smell of dead crickets and Folgers coffee — those once lovely canfuls.

For a long time, that same feeling, that of my own emotions synching up with those described by a poem, eluded description. For me, it was ineffable. The connection with a poem, with a poet, while one of the strongest that I felt, sidestepped definition. Appropriately though, in his essay “Feelings Into Words,” collected in Preoccupations, Heaney provided an answer for the question he had raised:

For a long time, that same feeling, that of my own emotions synching up with those described by a poem, eluded description. For me, it was ineffable. The connection with a poem, with a poet, while one of the strongest that I felt, sidestepped definition. Appropriately though, in his essay “Feelings Into Words,” collected in Preoccupations, Heaney provided an answer for the question he had raised:

Finding a voice means that you can get your own feeling into your own words and that your words have the feel of you about them; and I believe that it may not even be a metaphor, for a poetic voice is probably very intimately connected with the poet’s natural voice, the voice that he hears as the ideal speaker of the lines he is making up. How, then, do you find it? In practice, you hear it coming from somebody else; you hear something in another writer’s sounds that flows in in through your ear and enters the echo chamber of your head and delights your whole nervous system in such a way that your reaction will be, ‘Ah, I wish I had said that, in that particular way.’ This other writer, in fact, has spoken something essential to you, something you recognize instinctively as a true sounding of aspect of yourself and your experience.

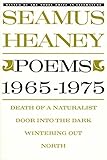

For me, Heaney was the place where I definitively heard that voice in several aspects — from his content down to individual phrases and chunks of sound. Heaney wrote, especially in his early volumes, of life in rural Northern Ireland and all that entailed, from the loss of a livelihood earned through manual labor and agriculture in Death of a Naturalist and Door Into the Dark to the way in which the political concerns of the Troubles were embedded in the very archaeology of the place in his magnum opus, North. The sense of place in his poetry is extraordinary. For me, his content choices were much more than examples of Heaney taking up the old poetic mortar and pestle of “to be universal, you must be local,” they unfolded the world of poetry for me in places where I didn’t even realize there were creases.

For me, Heaney was the place where I definitively heard that voice in several aspects — from his content down to individual phrases and chunks of sound. Heaney wrote, especially in his early volumes, of life in rural Northern Ireland and all that entailed, from the loss of a livelihood earned through manual labor and agriculture in Death of a Naturalist and Door Into the Dark to the way in which the political concerns of the Troubles were embedded in the very archaeology of the place in his magnum opus, North. The sense of place in his poetry is extraordinary. For me, his content choices were much more than examples of Heaney taking up the old poetic mortar and pestle of “to be universal, you must be local,” they unfolded the world of poetry for me in places where I didn’t even realize there were creases.

2.

My father grew up on a rabbit farm and helped his father poach from the National Forest for supper, while my mother’s family of nine planted five acres of potatoes to live on through the winter, her father making his meager living skidding pine logs with mules. My mother’s family didn’t have indoor plumbing until the late 1960s and used a dug well, complete with bucket and windlass, for water. Home for me is the Ouachita Mountains, a place even more innocuous then pre-Troubles Ulster: a small mountain range 500 miles from the ass end of the Appalachians.

In Heaney’s voice I found a license, almost an imperative, to write about the basic things that I had grown up around; if Heaney’s Moyola and Castledawson and Mossbawn mattered and had something profound to offer the world, so did my own region straddling the Arkansas-Oklahoma state line. I should have seen this before; I had been reading Frost and certainly could have picked up the same things from him, but, lovely as Frost is, his New England didn’t resonate with me in the same contorted but insistent ways that Heaney’s Northern Ireland did. Why is that? For me, it amounts to how I identified with Heaney’s voice.

Heaney’s voice went much deeper than regionalism, not only in his persistent archaeological motifs, which critics have identified as representative of the collective unconsciousness, but in the basic noise of his poems — the tangible aural sensations that create meaning almost independent from the semantics of the language, scraping down even further into the unconscious. When Heaney writes of bringing his grandfather “milk in a bottle corked sloppily with paper,” he works nearly with onomatopoeia, what his mentor Philip Hobsbaum termed “Heaneyspeak,” which I find to be little more than a cute way of referring to Heaney’s poetic voice. Heaney’s obsession with sound (again, something I might have, in another life, first noticed in Frost and his “sound of sense”) struck me immediately. In “Blackberry Picking,” the line “where briars scratched and wet grass bleached our boots” provided a perfect nugget of voice, marrying sound — the words “briars scratched” and “bleached our boots” make the exact sound as the actions that they describe — with the larger concern of identifiable content. I have bleached a couple pairs of boots myself.

3.

I find a rightness, for lack of a better term, in Heaney’s voice on all levels. I don’t need to try to find exactly how the position of the tongue in pronouncing “Poised like mud grenades, their blunt heads farting” perfectly encapsulates the lines’ meaning, nor do I have to search for the tenuous relationship between Heaney’s description of the fearful transformation from tadpole to bullfrog in “Death of a Naturalist” with my own experience of catching and hatching tadpoles and being frightened by the plop of bullfrogs in my grandmother’s pond. Heaney’s voice is true, and it is readily apparent. That is enough. I don’t need the critics or Carl Jung to tell me that depictions of amphibian fear tap into the collective unconsciousness and that the water of the flax dam represents sex, further reinforced by the reproduction of the frogs, etc. etc. I read the poem and I know, in a very visceral way, that Heaney has gotten something very right, that his voice has executed a perfect arpeggio in a brilliant cadenza.

4.

“Blackberry Picking” offered up yet another lesson in voice years after I first read it. I had always heard the poem in my own accent, and read it with my own voice. In a dialect that is firmly within the sphere of the upper American South, the only apparent rhyme in the poem is “clot/knot.” I had once read an essay that alluded to the “effective use of slant rhyme in the poem,” but did not offer any examples. I quickly assumed that the reference to “slant rhyme” was a mistake. Coming from a dialect which monophthongizes long “i” sounds to a fronted “ah” and merges the pronunciation of “pin” and “pen” to both sound as “pin,” the words “sun” and “ripen” don’t even come close to rhyming. The stress patterns of my own speech didn’t help. The word “ripen” is always pronounced with the stress on the first syllable, the second is diminished to the point of barely even being voiced. This manner of speech, which formed and forms my own internal reading voice, tends to take iambic pentameter out back for a good woodshedding, never mind that I didn’t really learn to even recognize iambs for a long while after encountering Heaney. In short, while the poem managed to strike me with great force, I was missing what amounts to half of Heaney’s craftsmanship. I didn’t discover any of this until I actually heard recordings of Heaney reading the poem, the way he heard it, in his own natural voice. Not only was every line in iambic pentameter, but every line rhymed in an array of brilliant little half rhymes. The heavens opened and light shone down illuminating, if nothing else, the full extent of Heaney’s skill.

5.

In Heaney’s fifth volume, North, he creates and interprets Ireland through its long history of Germanic incursions beginning with the Vikings. In the title poem, he imagines the voices of dead Vikings as “ocean-deafened voices” and “the longship’s swimming tongue,” which tells him:

. . . lie down

in the word-hoard, burrow

the coil and gleam

of your furrowed brain.

Compose in darkness.

Expect aurora borealis

in the long foray

but no cascade of light.

Keep your eye clear

as the bleb of the icicle,

trust the feel of what nubbed treasure

your hands have known.

In appropriating this archaeological voice, Heaney delivers a series of admonishments that are instructions to the poet as well as the reader. This voice is different, more ancient — unmetered stresses, no rhymes. It’s no wonder that Heaney wound up translating Beowulf; he was familiar with its voice, able to call it up from the “belly of stone ships,” to utter its implorement: “trust the feel of what nubbed treasure your hands have known.” This imperative struck me. “Trust!” it said; whatever your hands have known, trust in it. As long as your eye is clear, trust. Lie down. Burrow. Like Antaeus, be nourished by the soil, by a sense of place. Trust your place, trust your own geography, trust in your own culture, trust your own experience.

In appropriating this archaeological voice, Heaney delivers a series of admonishments that are instructions to the poet as well as the reader. This voice is different, more ancient — unmetered stresses, no rhymes. It’s no wonder that Heaney wound up translating Beowulf; he was familiar with its voice, able to call it up from the “belly of stone ships,” to utter its implorement: “trust the feel of what nubbed treasure your hands have known.” This imperative struck me. “Trust!” it said; whatever your hands have known, trust in it. As long as your eye is clear, trust. Lie down. Burrow. Like Antaeus, be nourished by the soil, by a sense of place. Trust your place, trust your own geography, trust in your own culture, trust your own experience.

For Heaney, this experience, this nubbed treasure, like all good treasures, is buried. As a poet, Heaney exhumes things. In “Bogland,” the last poem from Door into the Dark, he writes of the bringing up of ancient artifacts from Irish bogs, and that the bogs themselves “might be Atlantic seepage. / The wet centre is bottomless.” Speaking about the poem in an essay, Heaney notes that he derived the last line from hearing old people tell children not to play in the bogs because they were bottomless. This mining of memory is essential to Heaney’s poetry. In trying to access things that Heaney only half-consciously knows, he bores into my unconscious as a reader — the things that I too am only half-aware of. Maybe that’s why the feeling I get reading Heaney approaches inexplicable, conveyed only through metaphors of physical sensation: what Heaney has to say does something to my subconscious; his voice resonates there on that low level. It takes up residence with all the archetypes and shadows in the part of my psyche that, if mapped, would be labeled “Here Be Monsters” in ornate script wreathed in a facsimile of fog.

6.

Heaney’s most famous poem “Digging” set the tenor for his early work, celebrating the subterranean and particularly the role that writing plays in exploring it. The poem describes the memories Heaney has of his father and grandfather digging, but laments that “I’ve no spade to follow men like them,” then goes on to assert, “Between my finger and my thumb / the squat pen rests. / I’ll dig with it.” Like his grandfather who digs up turf for fuel, Heaney unearths a fuel that is no less important. Heaney once remarked that, to someone from his background, the word “work” meant physical work only, that one could not be “upstairs reading a book and say ‘oh, I’m working,’” and that “Digging” was partly a defense of his own way of life against the mores of his own culture. “Digging” shows the conflict between tradition and modernity. In this way it participates, in a meaningful way, in the development of Western thought. To be egregiously brief, the Ancient, Medieval, and Modern periods can be said to be concerned with humanity’s perception of conflict with three different iterations of higher power. The ancients conceived of gods who dealt out inescapable fate, then gods were replaced with a singular God who, though he was all powerful, still managed to allow evil in the world. Most recently, God has been replaced with science and technology, their conflict with humanity was probably first noticed by the Romantics and has persisted, more or less, until the present day. Heaney knew and lived that conflict — of watching his father’s occupation of cattle dealer fade away. It is equally important to me, in very practical terms. My grandfather worked in the timber, cutting down trees for a living, the next generation, my mother’s two brothers, were both carpenters, building houses from those same trees. My grandfather had a fourth grade education; my uncles finished only high school; I became a college boy and sure as hell can’t start cutting down trees for a living. In both a metaphorical and literal sense, all the trees have already been cut.

Maybe “Digging” seems old hat. It was written in the mid-1960s and was one of Heaney’s first poems. However, there is a reason that it is Heaney’s most anthologized poem. Its strident voice proclaims that poetry, that literature, is important in a time when the nutritional label on a box of Post-Toasties is considered a text and given equal status with Keats’s Odes.

7.

In “The Forge,” Heaney plainly states in the first line “All I know is a door into the dark,” then goes on to describe a blacksmith who “expends himself in shape and music,” who upon looking out his door at the passing lights of traffic, turns back inside “To beat real iron out, to work the bellows.” For a long time I read Heaney as looking out into the dark from inside the blacksmith shop, but I was wrong. Blacksmith shops are always dark so that the smith can properly see the color of the metal he’s working; different temperatures are indicated by the color, from reds to yellows and whites, each ideal for specific tasks: cutting, welding, drawing. Heaney looks in on this dark smithy; he has the capacity to see it, his eye is “clear as the bleb of the icicle.” His vantage point standing, as it were, with one foot in the past and another in the present allows him to see this murky scene. All his foundational knowledge is in these old ways; his family did not own a car when he was growing up, and his father plowed their fields with horses. Heaney “beats real iron out” as he dredges up these artifacts. The farther down one goes into the ground, the older things are, back even to the Iron Age: this is the basic tenet of geology and archaeology. Heaney is connected to these old, chthonic things. He disinters them and remembers them. In a sense, he members them again, creates them anew through his writing.

8.

Heaney gives the best explanation of what he does in the last poem of Death of a Naturalist. “Personal Helicon” is a poem about wells and Heaney’s fascination with them. Various wells are characterized as “So deep you saw no reflection in it,” “fructified” with “long roots” and in particular one that “had echoes, gave back your own call/ with a clean new music in it.” He ends the poem with:

Now, to pry into roots, to finger slime,

To stare, big-eyed Narcissus, into some spring

Is beneath all adult dignity. I rhyme

To see myself, to set the darkness echoing.

Heaney claims to see himself, not necessarily as an unadulterated reflection, but through echoes that come back up from the wells that he has dug into the darkness. The darkness of this well, bored into the deep strata of the unconscious, echoes with his voice and gives back a “clean new music.” Heaney writes as a means to hear himself, in order to truly ascertain his own voice. To do this he must work in the underground medium of his upbringing. It is the darkness that must be used to create the echo. The well must be dug deep, into those long, fructified roots of the subconscious, before it can echo. The discovery of this well and its echo is an exhumation, and even a bit of a resurrection. Though they are echoes, that “clean new music” carries a ring that comes from beyond the grave. And what grave is as deep as a well?

9.

In hearing Heaney’s voice echoing, I was able to get a sense of my own voice. I could use, at first at least, Heaney’s well to shout in, to see what came back, to find what those fructified roots are made of. Eventually I need to dig my own well, into my own fructified roots, with its own echo. Of course my own well may tap into the same underground spring as Heaney’s — perhaps all wells do — but I first needed Heaney’s well to become aware of what a well can do — of what digging can do. I needed Heaney’s voice to know what a voice could sound like, and through Heaney I discovered my own voice. I learned to listen to the timbre of its echoes.

10.

Seamus Heaney recently passed away. It was reported that his last words were a text message to his wife that read noli timere, which, translated into good King James English, is “Be not afraid.” Of course, Seamus was sharp enough to alter the conjugation from nolite timere found in St. Matthew, which is in the second person plural to the singular “noli.” This surprised me, not because a dying man still knew enough Latin to not only quote from the Vulgate but to give the proper conjugation on the fly, but rather than Heaney’s last words were via text message. My perception of him as a poet of the soil, one who spoke of thatched roofs and plowing by hand, was shattered by the news of his last words being transmitted via text message. Of course I read this news on a smartphone, but somehow it was still a staggering blow.

It only took me five minutes of careful thought to reestablish equilibrium. So what if Heaney and cellphones seemed incongruous to me? His life as a man of letters probably seemed just as contradictory to the people of his childhood. From the external world to our senses, from our senses to our brains, from our brains into language, from that language into writing, from the handwritten original to print in a book, from a printed book through the whole shebang again, back through taps of thumbs into a text message and radio waves, beams of invisible light, and a torrent of ones and zeros — it’s all just space between the infinite notches of Plato’s divided line.

Philo Farnsworth, inventor of the first electronic image pickup device that made television possible, was inspired by furrows of plowed earth and envisioned a device which reproduced images by scanning then reproducing them one row at a time. It wasn’t nearly as incongruous as I had thought. Heaney writes in his “Glanmore Sonnets” that,

Now the good life could be to cross a field

And art a paradigm of earth new from the lathe

Of ploughs. My lea is deeply tilled.

Arting a paradigm, that’s our real business. The medium doesn’t matter. Give us dancing electrons. Be not afraid. Dig with them.