Ad Age recently revealed that McDonald’s is getting into the publishing business. For the first two weeks of November, children’s books with a nutritional theme will replace the toys in Happy Meals. With titles like The Goat Who Ate Everything and Dodi the Dodo Goes to Orlando, the books are processed products through and through, created by the ad agency Leo Burnett, intended to create good press for the fast-food company by signaling its commitment to literacy and nutrition. McDonald’s ran a similar campaign earlier this year in the U.K., which inspired a list of satirical book titles (e.g., Harry Potter and the Deathly Swallows) under a #mcbooks hashtag on Twitter.The hashtag has been revived with the announcement of the new campaign.

![]() This is not, however, the first time McDonald’s has distributed children’s books. In 1979, when I was five years old, living in Wilmington, DE, my family took one of our painfully rare trips to McDonald’s to get Happy Meals for my sisters and me. There were few things more exciting at the time than opening up that iconic box to see what sort of toy was inside. On this visit, however, there was no toy. The counterperson handed over a little paperback with a drawing on the cover of a boy whitewashing a fence.

This is not, however, the first time McDonald’s has distributed children’s books. In 1979, when I was five years old, living in Wilmington, DE, my family took one of our painfully rare trips to McDonald’s to get Happy Meals for my sisters and me. There were few things more exciting at the time than opening up that iconic box to see what sort of toy was inside. On this visit, however, there was no toy. The counterperson handed over a little paperback with a drawing on the cover of a boy whitewashing a fence.

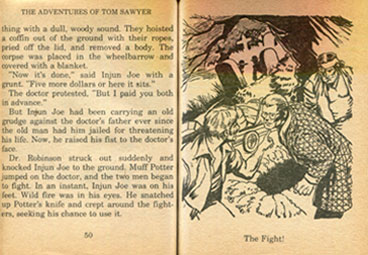

McDonald’s introduced me — and I would venture thousands of other kids — not only to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer but also to the notion of a classic. In 1977 and again in 1979, the fast food chain paired up with the publisher I. Waldman & Son to distribute Illustrated Classics Editions in their restaurants. Waldman had published children’s versions of classic literature, such as The Three Musketeers, Robinson Crusoe, and Moby-Dick, in 1977 under the brand name Moby Books and, in 1979, the publisher paired with Playmore, Inc. to distribute the series in supermarkets, drugstores, and other retail sites. They released 12 titles that year and another dozen in 1983. The books measured 5.5 by 4 inches and were typically 238 pages long, with each page of text facing an illustration.

Over the next few years, I collected a half dozen Illustrated Classics books, but that first encounter with The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was the moment when I discovered literature.

Granted, Deidre S. Laiken’s adaptation of Twain’s novel might not count for everyone as literature. Here is Twain’s opening:

“TOM!”

No answer.

“TOM!”

No answer.

“What’s gone with that boy, I wonder? You TOM!”

No answer.

Here is Laiken:

Tom Sawyer was always getting into trouble. He was the kind of boy who just could not resist adventure.

In this textbook example of the difference between writing that shows versus writing that tells, Twain gives us an immediate sense of what Laiken can only report to us. Tom Sawyer in the original is such a miscreant that he does not even bother to show up for the start of the novel that bears his name, while the Illustrated Classics version frames Tom’s character and the entire narrative for its readers, wary of letting us interpret too much on our own.

What really mattered to me in the long term, however, was not the quality of the text but the authority behind it. There were few institutions I respected more than McDonald’s, so when I saw that it had endorsed a line of books grouped under this mysterious rubric “classic,” I knew that this was a work worth reading. More significantly, I learned from McDonald’s that there was a whole class of books out there that were especially worth reading. I read a lot of junk as a kid — loads of books about movie monsters, World War II, and science fiction, plus a mountain of comics — but I took special pride in reading classics and presidential biographies and was thrilled when adults complimented me on my taste and sophistication.

All this reading and complimenting eventually led to a PhD in English from the University of California, Berkeley, where I learned that what McDonald’s had introduced me to at the age of five was the concept of cultural capital. The term comes from the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, and it refers to “forms of knowledge, skills, education, and advantages that a person has, which give them a higher status in society.” Speaking Standard English, knowing how to order and eat at a four-star restaurant, and being able to discuss art and music are all forms of cultural capital. They are ways of signaling one’s membership in a class and even of advancing within and beyond it. My primary motive for reading Illustrated Classics, to be sure, was pleasure (as is the case with my reading of literature today), but I was aware early on that some of that enjoyment derived from the sense of distinction I felt in doing so.

I used to enjoy the irony that I have held onto the taste for literature that I picked up at McDonald’s much longer than I did the taste for its food. Nowadays, I feel more wistful for a moment in time when a fast food company thought it could promote itself by providing kids with editions of Twain, Dumas, and Dickens. I am not naïve enough to think McDonald’s did so on account of its pure love of literature. The company entered into this promotion with the same sense of self-interest and desire for synergy that it did when it embarked on it first cross-promotion of a film with the Star Trek Happy Meal in 1979, the year the Happy Meal debuted. And in much the same way that this upcoming publishing endeavor is likely intended to wash away some of the association of the McDonald’s name with junk food and childhood obesity, the Illustrated Classics scheme was probably meant to raise the brow of a company whose main contribution to culture was a mountain of advertising featuring a creepy clown and his oddly shaped friends.

What seems unbelievable now — and even sweet — is that McDonald’s ever cared about its brow enough to try raising it. McDonald’s and I had that in common: we wanted to elevate ourselves by association with the classics, only I held onto that desire long after the fast food chain did. I went to grad school for a lot of reasons, but McDonald’s Illustrated Classics played their own little part in that decision. It’s not a choice I regret, but, in this deeply pessimistic moment for English departments, I cannot help but feel nostalgic for a time when literature’s cultural stock was so high that even McDonald’s wanted to invest in it.