As if rap’s global pop influence isn’t justice enough, the campaign to document its musical and commercial developments, the lives of its artists, important artifacts and its intersection with recent history has gained great momentum in the literary space — when not making bold claims on Literature itself. A twenty-first-century given, rap has even wended its way into that beacon of the twentieth century, the anthology. Yale University Press’s The Anthology of Rap flays memorable tracks, preserving their lyrical skins for the hasty forceps of future scholars “within the context of African American oral culture and the Western poetic heritage.” Anthologies upholding a great heritage are necessarily short on the specifics. Yet there is also a rebellious potential within the anthology itself, recovering moments that tradition or fashion have invalidated.

As if rap’s global pop influence isn’t justice enough, the campaign to document its musical and commercial developments, the lives of its artists, important artifacts and its intersection with recent history has gained great momentum in the literary space — when not making bold claims on Literature itself. A twenty-first-century given, rap has even wended its way into that beacon of the twentieth century, the anthology. Yale University Press’s The Anthology of Rap flays memorable tracks, preserving their lyrical skins for the hasty forceps of future scholars “within the context of African American oral culture and the Western poetic heritage.” Anthologies upholding a great heritage are necessarily short on the specifics. Yet there is also a rebellious potential within the anthology itself, recovering moments that tradition or fashion have invalidated.

Nicholson Baker invented such a noble anthology-wright in his short novel, The Anthologist, a miscellaneous monologue by working poet Paul Chowder that bears many of the features for which Baker has been rightly admired, his vivid observational miniatures and giddy disclosures, his nimble, various excursions, his paring back vast erudition to a buoyant, demotic language. Chowder takes seriously a poet’s claim to common experience and finds in the free-verse Modernists an estrangement from the four-beat line, which he considers “the soul of English poetry.” (Drawing on the recent theory of “unrealized beats,” he further insists that iambic pentameter subconsciously adopts a caesura as a sixth beat, morphing into a “swaying three-beat minuetto.”) The light verse and rhyming ballads that get crowded out by the followers of Eliot and Pound stake the truer claim to listeners’ hearts and minds by accommodating our innate habit of matching similar sounds. Holed up in his heaping New Hampshire barn, past deadline on the introduction to his anthology, Only Rhyme, Paul Chowder takes Sharpie to easel pad and diagrams the many stresses of his professional and personal discontents.

Nicholson Baker invented such a noble anthology-wright in his short novel, The Anthologist, a miscellaneous monologue by working poet Paul Chowder that bears many of the features for which Baker has been rightly admired, his vivid observational miniatures and giddy disclosures, his nimble, various excursions, his paring back vast erudition to a buoyant, demotic language. Chowder takes seriously a poet’s claim to common experience and finds in the free-verse Modernists an estrangement from the four-beat line, which he considers “the soul of English poetry.” (Drawing on the recent theory of “unrealized beats,” he further insists that iambic pentameter subconsciously adopts a caesura as a sixth beat, morphing into a “swaying three-beat minuetto.”) The light verse and rhyming ballads that get crowded out by the followers of Eliot and Pound stake the truer claim to listeners’ hearts and minds by accommodating our innate habit of matching similar sounds. Holed up in his heaping New Hampshire barn, past deadline on the introduction to his anthology, Only Rhyme, Paul Chowder takes Sharpie to easel pad and diagrams the many stresses of his professional and personal discontents.

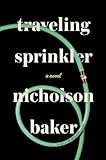

Paul Chowder returns in Baker’s new novel, Traveling Sprinkler, which isn’t so much a sequel as a remake. It is a novel-rhyme; the two comprise a couplet. Following the real-time interval between novels, a few years have passed and Only Rhyme continues to sell at some big schools in the southwest. The poet’s editor nudges him for a book of new poems, but there is nothing like the claustrophobic pressure that surrounded the previous labor. We already know of his productive return flight from a conference in Switzerland, when he wrote twenty-three poems. Communication lines are still tentatively open with ex-girlfriend Roz, who makes egg salad sandwiches for his fifty-fifth birthday. Paul Chowder has extended his sphere. Instead of the chin bar in his barn, he works out at Planet Fitness, a “Judgment Free Zone.” He attends Quaker meetings. He buys a guitar. Also a keyboard and a microphone. A nagging thirst for Yukon Jack has been displaced by a curious flirtation with cigars. He writes and works out melodies in the car. His middle-aged neighbor Nanette once nervously threw him a leftover Meals on Wheels chicken dinner and saved him from sabotaging her new hardwood floor. Now he has Nan and her son over for sushi, reliably babysits her chickens and waters her tomatoes with his traveling sprinkler.

It is the historian within the anthologist that presses toward the now. Tim, a professor at Tufts who completed a book on Queen Victoria’s imperialistic rule, informs Paul about the movement to challenge Obama’s use of drones in current conflicts. As Tim, always Paul’s hand in the world, reports from the latest rally, the poet becomes more disturbed by his readings on the issue and his consumption of related online media, like videos and protest songs. Paul is left “traumatized and angry” by the story of Roya, a thirteen-year-old taken to begging on the Afghanistan/Pakistan border after her mother and two brothers were killed in a 2002 drone attack and her father “carefully gathered pieces of his wife and his sons from the tree near their house and buried them.” Pacing in his kitchen, Paul feels “powerless and ineffectual.” If in the academy Paul’s minority defense of rhyme was somewhat vindicated, his revulsion toward American war tactics leaves him politically marginalized. But both minorities are appeals to common experience overrun by institutions. Atrocities can affect observers remotely, like poems. The poet’s response, the only response that registers on an individual level, is tangential and local. Tim recruits Paul to write a protest song. Much of Traveling Sprinkler follows this trajectory, but only in Paul’s meandering Chowderesque way.

The authorized history of hip hop’s cultural and musical expansion is that of local, folk origins. The DJ presided over the ceremony, providing rhythmic instructions to partygoers to maintain the music’s momentum. In time, these MC duties were outsourced to vocal specialists who conjured additional layers of narrative and linguistic complexity that survive, but in a different form, the party-event. Paradoxically, it is the MC’s flow — the delivery system of the lyrics, rooted in nonverbal features of the song — that enables the recognition of the words in anthology. This, too, was the radical notion behind Only Rhyme, assembling a book that isolates sounds. If Bob Dylan, whose lyrics also have been printed and bound, is awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, the proper objection isn’t regarding his songwriting but the singing quality of poetry. In The Anthologist, Chowder explains: “We like to visit the parallel sound-studio universe…independent of the other part of our head, which is the conscious part.” If rhyme serves an aural function in poetry, “music fogs over” the consonant particulars of lyrical rhyme. Music, the overarching concern of Traveling Sprinkler, “is about the idea that one cellist’s A is going to sound slightly different than another cellist’s A.” In written notation, of words or music, “there are losses incurred.” The plurality that reigns over head music is curtailed “by a black blob on a page.” The liberated anthologist burns a mixtape CD and gives it to Roz, his reluctant though accessible muse, the anti-Laura. Always the omnivore, Paul digs current and classic pop songs while also meditating in long stretches on classical composers, but from the underdog perspective of the bassoon. Stravinsky, influenced by Debussy, chose a solo bassoon to open The Rite of Spring, but tortures it by forcing it into the register of the flute. In spite of its limits, the woodcraft bassoon provides an organic connection to spring, while the flute is “a tube of metal.” Paul’s jaw is shot from playing the bassoon when he was younger, but he enjoys building his repertoire of guitar chords and also gains pointers from Nanette’s nineteen-year-old, Raymond, who composes rap songs digitally. Paul assembles an orchestra from the everyday, feeding his Logic digital audio workstation with the plucking of an egg slicer and the sloshing of a pasta pot, which he can manipulate on his new MIDI keyboard.

Technology enables the poet to complete the reductionist’s journey from language’s music to the fundamental elements of musical sound. In The Anthologist, Paul relays warnings from big names like Elizabeth Bishop and W. H. Auden against the growing Big Business of poetry. “Philip Larkin said that when you start paying people to write poems and paying people to read them you remove the ‘element of compulsive contact.’” His sense of powerlessness toward affecting change in society as writer of verse compels Chowder to retread his domain and seek out regions of compulsive contact with people rather than listing under faceless institutions. Raymond inhabits such a space, working away at original compositions on his computer while also DJing at a local club, college-age but taking time off, knowledgeable yet unaccredited. Raymond and Paul’s partnership, promiscuous and unauthorized, embodies the best virtues of the social media over which Paul devotes increasing time, to share songs, watch video, read political discourse, and self-educate his musicianship. His competition with dead critics finds a logical resolution in active, real-time exchanges with the living nonce.