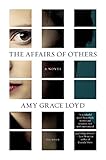

Amy Grace Loyd, the executive editor of Byliner and a former fiction and literary editor at Playboy, has edited some of the best writers of our time. She’s developed her own confident and refined style of storytelling and shows it in her sensuous debut novel, The Affairs of Others. In expansive and precise language, Loyd explores the rhythms and sensations of human arrangements and exposes layers of time, grief, and love in contemporary urban life. Lloyd’s writing often takes its time. She wants the reader to pause and savor her notes that city rain has a “mineral” smell or sorrow has a “peculiar altitude.”

Amy Grace Loyd, the executive editor of Byliner and a former fiction and literary editor at Playboy, has edited some of the best writers of our time. She’s developed her own confident and refined style of storytelling and shows it in her sensuous debut novel, The Affairs of Others. In expansive and precise language, Loyd explores the rhythms and sensations of human arrangements and exposes layers of time, grief, and love in contemporary urban life. Lloyd’s writing often takes its time. She wants the reader to pause and savor her notes that city rain has a “mineral” smell or sorrow has a “peculiar altitude.”

Loyd’s real success is evident in two areas: sex and the city. She reconstructs the moods of post-9/11 New York, most especially in her narrator, Celia Cassill. Reflecting the recent history of her city, Celia is a bruised and barricaded young widow who has created spaces that she can carefully control. She keeps herself physically and emotionally apart from others, and remains anchored in an ongoing mourning for the past and her husband.

Loyd is expert in describing Celia’s trampled and tentative Brooklyn neighborhood. She conjures the streets, sidewalks, and the subway of the city as places that both connect and separate people simultaneously. She communicates precisely how wide streets, like Atlantic Avenue, form divisions between neighborhoods as well as demarcating the past from the present in people’s minds.

Loyd creates a microcosm of the city landscape in Celia’s apartment building. Celia is the landlady — at once connected to her tenants and deliberately set apart from them, at once living in the past and yet occasionally tugged into the present.

While Celia’s husband has been dead for five years, she has not gotten over the loss, and actually doesn’t see anything wrong with remaining immersed in her past. Her husband left her enough money for her to buy a building and become a landlady to a small, carefully selected group of tenants. She has rules and routines, carefully guarded and prescribed interactions with her neighbors, and a respect for the privacy of others she offers in exchange for them respecting her boundaries. Celia keeps to herself and her memories, and Loyd is careful to reflect this behavior in other city dwellers who experience life along the same lines — connected and apart, present and distant.

But there’s always an inciting incident in city life — and novels — to shake up a comfort zone and ignite change. Loyd introduces the charismatic Hope into Celia’s static world, and the walls come tumbling down. Subletting from a trusted tenant, Hope moves into Celia’s building, and triggers a progression of events that break down barriers among the fragile occupants. The elderly tenant on the top floor goes missing. The married couple on the floor below him begin fighting and separate. Hope is on the run from a failed marriage and begins a sexually violent affair with a hulking troubled lover. And Celia herself is disturbed by the stirrings of desire and violence in the rooms above that force her to confront the limitations of her serene isolation, and how she has been navigating her life.

Celia is pulled out of her orderly stasis and yanked into the connected lives of her tenants. Loyd has her narrator break bad in some surprising ways. Soon Celia is exchanging violent slaps with the adult daughter of her missing tenant; eavesdropping on the unmistakable sounds of Hope being bent over a table by her dominating lover; knocking out a man with a golf club; violating privacy in every way imaginable by invading her tenants’ apartments and snooping through their pockets, diaries, and beds. Celia’s journey is a wonderfully disturbing and satisfying passage through mourning and toward rejoining the world.

Loyd describes urban characters and urban places as codependent entities, extensions of each other. Sometimes bodies become places — which brings us to how Loyd writes about the erotic vibrations in her characters.

This writer gives good sex. Loyd avoids the pitfalls of bad sex writing almost assuredly because she avoids describing body parts — this seems to be the key. (She does falter once and it jars — but then the reader plunges back in.) The Affairs of Others isn’t an instance of what a dirty-book-weary friend mockingly calls “sexual fiction,” it’s a triumph of describing what is sensed and experienced during sex rather than what is performed or penetrated in the sex act. Celia experiences sex — when she engages in or overhears it — much like she experiences her city, as both threat and connection, distance and intimacy. It’s a way for her to violate her own privacy — whether she’s eavesdropping on Hope and her lover or starting an affair herself that may bring her back into the present world.

The Affairs of Others captures the moods of a tired city and of a mourning widow, both reluctant to find renewal. Loyd often deploys the noirish tones of a mystery novel in the search for the missing tenant, various violent confrontations, and several visits from a police detective — and this is the right mood for her narrator’s journey. In true cherchez la femme-mode, Loyd places a woman at the source of all that has been disturbed in her narrator’s life, but it’s not only Hope the interloper who has forced Celia to break down her carefully built boundaries — it’s Celia’s own human desire to be alive to the possibilities of being part of the lives of others.