The last time I saw Elmore Leonard alive was in 2004 at a now-defunct New York bookstore, where Leonard had come to promote his latest novel and I had come to pay homage to a literary hero.

The novel was called Mr. Paradise. I lurked in the back of the store while a long line of fans waited to get their books autographed, maybe exchange a few words with the author. The atmosphere was more like a church than a place of business, for Leonard had developed a large, loyal, and nearly reverent following during a career that had been chugging along for more than half a century by then and kept on chugging until Tuesday, when Leonard died at 87 at his home near Detroit.

The novel was called Mr. Paradise. I lurked in the back of the store while a long line of fans waited to get their books autographed, maybe exchange a few words with the author. The atmosphere was more like a church than a place of business, for Leonard had developed a large, loyal, and nearly reverent following during a career that had been chugging along for more than half a century by then and kept on chugging until Tuesday, when Leonard died at 87 at his home near Detroit.

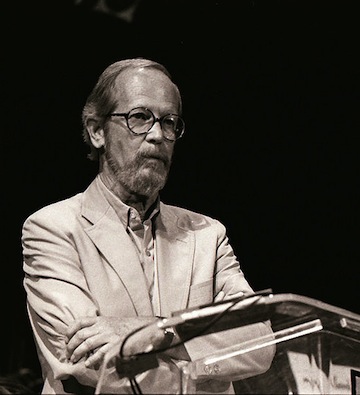

As Leonard signed books that day in New York, I noticed that he rarely looked up and he exchanged a minimum of small talk with his fans. He was well into his 70s by then, and the book-flogging drill had obviously lost its luster for him long ago. In that moment I realized my act of homage was going to be even trickier than I’d feared. I had been a fan of Leonard’s writing for years,so I didn’t doubt my sincerity. But I could see that paying homage to a writer as famous and seasoned as Leonard was a fraught transaction. It’s almost impossible not to come across as sycophantic and fawning. Or, worse, creepy.

When the last fan had gotten his book signed, I took a deep breath and stepped up to the table. Leonard gave me a look I took to be frosty. ALWAYS A STRAGGLER, it seemed to say. I held out a signed copy of my own first novel, Motor City, and said, “Mr. Leonard, my name is Bill Morris. I played football with your son Pete at Holy Name School back in the ’60s. I wanted to give you this copy of my first novel and let you know I’ve loved your writing for years.”

Leonard’s face changed. A warm smile melted the frost. He thanked me for the book, asked after my parents, who he claimed to remember, told me with evident pride that his son Pete had started publishing novels of his own, which I knew. Terrified of pressing my luck, I cut the conversation short, thanked him and left the store. Leonard’s warmth had been palpable. So had his relief that his duty was done — until next time.

The first times I saw Elmore Leonard were in the 1950s and ’60s, when we were living near each other in a Detroit suburb and I was playing football with his kid. All I knew about Pete’s dad back then was that he wasn’t like my father and most of the other fathers in the neighborhood, who boarded big shiny cars in the morning and went off to make money making cars. Mr. Leonard was different. He worked in something mysterious called advertising — then came home and wrote stories and novels. Even as a grade schooler, this struck me as impossibly romantic and exotic. It was possible for a respectable middle-class man to be a writer, an artist!

Leonard was rightly revered for his impeccable ear for spoken English, his clean prose, his insistence that the author must remain invisible, and that writing should never be writerly.

But I think his achievement went well beyond what was in his books — and in the uneven movies they inspired. Leonard won the favor of some high literary types, including Walker Percy and Martin Amis, a sign that he had accomplished something that once seemed unthinkable: he lifted genre writing out of the ghetto and made readers and critics see that fine writing cannot be bottled or diminished by labels.

Loren D. Estleman, another prolific Michigan-based author of high-quality crime and western fiction, was saddened by the news that his friend Elmore Leonard had died. “All he cared about was his work,” Estleman said by phone on Tuesday. “He was the absolute last of the ad men — the Mad Men — who went from writing ad copy to writing for the pulps and then on to the world market of writing quality novels.”

Leonard was among a handful of pioneers — Philip K. Dick, George V. Higgins, and John le Carré also come to mind — who opened the world’s eyes to something that now seems self-evident: the quality of the writing is the only thing that matters.

I’ve often wondered if Elmore Leonard read that novel I gave him back in 2004. Probably not. I don’t care. It was enough to spend a few moments in the presence of an immortal.

Image Credit: Wikipedia