I recently made the mistake of confessing a fantasy to a friend. I told him I dreamed of being a reclusive writer. Tame, I know, given the whole point of a fantasy is to go whole hog. Yet isn’t there something incredibly seductive about those mysterious figures who hide away? We imagine them toiling away in a remote mountain cabin or a Manhattan apartment and only rarely, and with much fanfare, releasing dispatches through an intricate web of agents and lawyers, dispatches that allow an anxiously waiting reading public to make sense of the chaos that has become our world. A guru who bursts forth every thirteen or seventeen years like a cicada.

Hermit, Thoreau wrote. I wonder what the world is doing now.

My friend cut to the chase. “You’re not famous enough to be reclusive,” he said. “Actually, you’re not famous at all. Maybe you’ll get some traction after you’re dead?”

Apart from the obvious — i.e., there’s always death and the possibility of posthumous resurrection — my wise friend might also be right that a person might need a certain amount of celebrity in order to be known for having disappeared. And to my discredit, deep down, I admit this is pretty attractive. I want to retreat from the world and think and write in solitude. At the same time I wouldn’t mind a few readers knowing I’m out here being all mysterious.

Orner? Wait, didn’t he kick for the Vikings?

No, no I’m talking about the writer, you know the dude that vanished…

A genuine recluse, of course, wouldn’t give a damn.

Lately, I’ve wondered if this odd fantasy is rooted in my uneasy relationship with how connected we all are with each other these days. Not long ago I was at a Literary Festival (so much for being reclusive) and I attended a panel discussion about the future of the book as the book. The prognosis, I learned, is inconclusive. Might have a few actual physical books in the future, might not. Only one thing didn’t seem in doubt at all, and that is the future of the writer of these inconclusive books. This future, we were told, is directly tied to having a personal online presence. A writer, one panelist declared, who doesn’t personally reach out to readers via social media is DOA.

This was alarming for several reasons. One is that I’ve tried it. I’m never quite sure what to say. I’ve shared things my friends are doing. “Teddy Finkel just got back from the trip of a lifetime in Banff!” I’ve also posted a few things I’m up to as well. But each time I’ve done so, there’s this dread. The impulse — now an industry — to spread good news about oneself far and wide has become soul-crushing. It makes me want to retreat into the garage (where the Wifi can’t find me) with my outmoded books and unfinished manuscripts. Maybe I’m just not that good at being myself. I’ve come to see social media as a skill like anything else. Some are talented at it; others, less so. I’m a mediocre interior decorator also. Nor can I cook, change the oil, or dance.

And yet if I don’t I’m DOA?

There is, though, a larger issue at stake. For me, the whole point of fiction has always been to forget about me. To paraphrase Eudora Welty, the most elemental aspect of the art of fiction is the challenge of seeing the world through another person’s eyes. I spend much of my life trying to live up to Welty’s gauntlet. There is something about the increased demand that fiction writers speak as themselves that feels like a violation of what I used to hold so sacred, the tenet that it is not about me but about the characters I create. I’ve always considered inventing people and introducing them into an already crowded, indifferent world to be an act of faith. The only faith I’ve got. It’s my way of saying that I love this planet and its people in spite of everything we do every day to kill it — and each other.

Obviously, social media itself isn’t the trouble. The crux, as I see it, is that lately the substance of what we create is often considered almost incidental to the way that we writers, personally, market our product. We now must sell our books like we sell ourselves. During the panel discussion on the future of the book, for instance, what goes inside the books in question received passing, almost grudging mention. It isn’t the first time I’ve noticed this trend. Just yesterday I read a piece about pricing in self-published e-books. Apparently $3.99 is the sweet spot? Sweet spot? Am I a dinosaur to wonder what this $3.99-dollar book is actually about?

And yet, paradoxically, I find that this almost fanatical focus on sales over content might provide the alternate route of escape. No need to flee to the cabin in the Bitteroot just yet, as appealing as this sounds. Maybe I can live out my reclusive dream by hiding in plain sight, by choosing not to engage personally on-line, to declare myself, on my own terms, DOA.

Don’t do it, the experts cry. Besides being a recluse has been out since Cormac McCarthy went on Oprah. Forget it, you want to be read, you got to sell baby sell.

But do we? Really? When for so many of us out here have a hard enough time inventing lives that aren’t our own?

It may say too much about me that I take my life not only from Eudora Welty, but also from the beautifully goofy movie Say Anything. I’m a child of the 80s, what can I say? You remember Lloyd Dobler? I don’t want to sell anything, buy anything, or process anything as a career. I don’t want to sell anything bought or processed, or buy anything sold or processed…

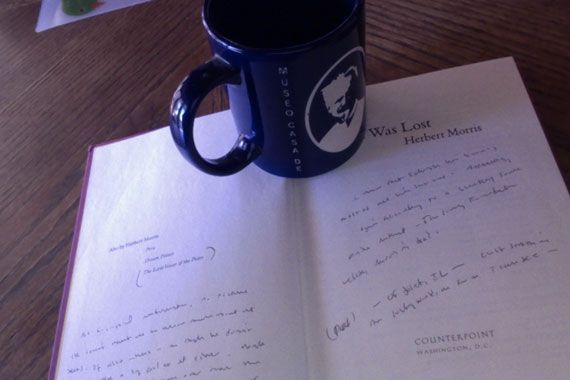

I take solace in the example of writers who, in spite of all trends, have gone another direction. On my desk, right now, I have a book of poetry by a man named Herbert Morris. Aside from his six books, the fact that he attended Brooklyn College, and the date of his birth (1928) and death (2001), almost nothing, as far as I can tell, is publicly known about him. The man clearly wanted it this way.

On the jacket of What Was Lost, his last book, published in 2000, there is no author photo, no biographical information, and no acknowledgements. Richard Howard deepens the mystery with a quote: “Always the dark stranger at Poetry’s feast of lights, Herbert Morris has returned to haunt the banquet with these fifteen notional ekphrases, surely the most generous creations American culture has produced since Morris’s own Little Voices of the Pears.”

On the jacket of What Was Lost, his last book, published in 2000, there is no author photo, no biographical information, and no acknowledgements. Richard Howard deepens the mystery with a quote: “Always the dark stranger at Poetry’s feast of lights, Herbert Morris has returned to haunt the banquet with these fifteen notional ekphrases, surely the most generous creations American culture has produced since Morris’s own Little Voices of the Pears.”

It took me three dictionaries to track down the word ekphrases. A gorgeous word, it means a concentrated description of an object, often artwork. Apt as it applies to Morris whose poems are all about paying attention – truly seeing.

I may have found my recluse, minus any fame, in this dark stranger. I only have his poems, not his personality, but they are exactly what I need. For me it takes great concentration to read What Was Lost, and thus, I slow way, way down as I follow the tangled, meandering thoughts of his intensely lonely characters. Morris may be a poet, but he is also, to my mind, among the most hypnotic fiction writers in contemporary literature. I fall into a Morris poem the way I do into a Sebald novel. It is a whole immersion into the intensity of a moment.

Morris writes of other people, sometimes well-known people, such as Henry James or James Joyce, in moments of profound isolation. One utterly breathtaking poem “History, Weather, Loss, the Children, Georgia” is about a photograph taken of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt as they sit in a car before a group of schoolchildren. The photo was snapped just before the children began to serenade the president. The poem begins slowly, exquisitely, as Morris constructs the scene through the smallest of details about the children. They’ve been rehearsing all week for this occasion. Their mouths are poised, frozen forever in little O’s. Even the threads of their clothes receive attention. As does the hand printed banner, Welcome Mister President. Only toward the very last lines does the poem zero in on Franklin and Eleanor themselves. These two icons may be long dead, as is this haunted moment in Warm Springs, Georgia in 1938. And yet, and this is where the poem aches, Franklin and Eleanor are not historical props but rather two vulnerable human beings sitting together — apart — in the back of an open car. The poem delicately, yet vehemently, chastises Franklin for “his wholly crucial failure” to do something pretty simple and that’s touch his wife.

or once, once, whisper to her

intimacies any man might well whisper

on the brink of the heartbreak of the Thirties

(the voiceless poised to sing, air strangled, sultry,

the music teacher’s cue not yet quite given…

I imagine Morris, whoever he was, staring at this photograph so long and with such absorption that Frankin and Eleanor began to sweat in the humid air. And still Franklin’s fingers don’t reach for her. The poem mourns the loss of so many things, including this touch that never happened.

Ultimately this is not only what I crave as a writer, but as a reader of fiction. I want living, breathing, flawed characters on the page. Now more than ever I want to know about private failures not publically shared triumphs. Herbert Morris gives us the miracle of other people in their intimate, unguarded moments.

He may not have trumpeted himself when he was alive. He kept himself apart, and the details of his own life out of the equation. Perhaps as a consequence he may not have sold many books, but even so he found his way to my desk. I dug him out of the free bin outside Dog Ear Books in San Francisco. How can I express my gratitude to a man who never sought it, who only wanted me to know his creations, not their creator? And think about it, how many others might be out there, somewhere, under all this noise, telling us things we need to hear?

Photo courtesy of the author.