Willa Cather did not want her letters published, ever. She could not have been clearer or more emphatic on this point. There is, then, a respectable argument that Selected Letters should not be in the world, inasmuch as its publication does violence to the wishes of the very author whose legacy this book’s editors purport to serve. I am inclined to disagree with that argument, but I find it impossible to state the affirmative case for posthumous publication of letters and unfinished texts in terms I would care to defend. The facts of each case are so stubbornly different. To the publication of Fitzgerald’s The Love of the Last Tycoon one is inclined to say “Yes;” to the publication of Hemingway’s True at First Light one is inclined to say “No.” Critical scruples are likely beside the point, in any event. Where there is a market for publication, publication will eventually occur; that is the inexorable commercial logic. One simply wishes it to be done well rather than ill.

Willa Cather did not want her letters published, ever. She could not have been clearer or more emphatic on this point. There is, then, a respectable argument that Selected Letters should not be in the world, inasmuch as its publication does violence to the wishes of the very author whose legacy this book’s editors purport to serve. I am inclined to disagree with that argument, but I find it impossible to state the affirmative case for posthumous publication of letters and unfinished texts in terms I would care to defend. The facts of each case are so stubbornly different. To the publication of Fitzgerald’s The Love of the Last Tycoon one is inclined to say “Yes;” to the publication of Hemingway’s True at First Light one is inclined to say “No.” Critical scruples are likely beside the point, in any event. Where there is a market for publication, publication will eventually occur; that is the inexorable commercial logic. One simply wishes it to be done well rather than ill.

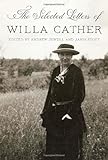

The Willa Cather Trust is unusual among such bodies in that its decisions regarding the disposition of Cather’s remnants are made with substantial scholarly input. Here the trustees chose their editors well. Janis Stout is the author of perhaps the best conventional Cather biography (Willa Cather: The Writer and Her World), and Andrew Jewell is the keeper of the substantial Cather Archive at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Stout and Jewell undertook a considerable task of selection, and they seem to have been content to let the letters that survived their winnowing process stand largely on their own. Perhaps they could have done more to place the letters in relief against Cather’s contemporaneous work and the signal events of her life. But they could also have done more harm, through either persistent intrusion or stubborn over-reading of the letters. Their understated approach mitigates any insult to Cather’s privacy done by the choice to publish.

The Willa Cather Trust is unusual among such bodies in that its decisions regarding the disposition of Cather’s remnants are made with substantial scholarly input. Here the trustees chose their editors well. Janis Stout is the author of perhaps the best conventional Cather biography (Willa Cather: The Writer and Her World), and Andrew Jewell is the keeper of the substantial Cather Archive at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Stout and Jewell undertook a considerable task of selection, and they seem to have been content to let the letters that survived their winnowing process stand largely on their own. Perhaps they could have done more to place the letters in relief against Cather’s contemporaneous work and the signal events of her life. But they could also have done more harm, through either persistent intrusion or stubborn over-reading of the letters. Their understated approach mitigates any insult to Cather’s privacy done by the choice to publish.

This volume comes 18 years after Joan Acocella’s lacerating New Yorker essay, “Cather and the Academy” (later published in book form as Willa Cather & the Politics of Criticism, which resolved certain conflicts within Cather studies the same way the atomic bomb ended World War II: by destroying one side’s ability to fight. Acocella, herself a feminist and critic of strong conviction, took on the feminist and queer critics in the Cather field, accusing them of shrillness, tone deafness, and ultimately bad faith. These charges stuck, and subsequent readings of Cather have returned to core principles of literary criticism — which is to say they have returned to the texts.

This volume comes 18 years after Joan Acocella’s lacerating New Yorker essay, “Cather and the Academy” (later published in book form as Willa Cather & the Politics of Criticism, which resolved certain conflicts within Cather studies the same way the atomic bomb ended World War II: by destroying one side’s ability to fight. Acocella, herself a feminist and critic of strong conviction, took on the feminist and queer critics in the Cather field, accusing them of shrillness, tone deafness, and ultimately bad faith. These charges stuck, and subsequent readings of Cather have returned to core principles of literary criticism — which is to say they have returned to the texts.

Cather was one of nature’s miracles, possessed from an early age of an unaccountable conviction that she was meant for something. Yes, she was female, and she lived in Nebraska. The world of letters was a long way away in every sense. Cather could not have been unaware of these facts. But as Acocella puts it, Cather simply opened the door to artistic freedom and walked through it. Seeing that there was a door was Cather’s first and greatest feat of imagination. For several centuries of women that had preceded her, there had only been a brick wall, extending in either direction as far as the eye could see. But at the same time that Virginia Woolf labored heroically to give expression to a female artist’s entitlement, Cather simply assumed it.

Another striking thing about Cather as a social being is how little anxiety she appears to have had about status and class, even while rising vertiginously from rural obscurity to warm correspondences with H.L. Mencken, Alfred Knopf, and Sinclair Lewis. She wrote to these “great men” (and some great women, too; Sarah Orne Jewett, for example, was a frequent correspondent) without anxiety, in her own voice, without wheedling or special pleading, displaying an intelligent ease, and her correspondents replied in kind. One is tempted to say that as a woman from Red Cloud, Nebraska, she was so much an outsider as to be free of the more complex and intractable concerns about status from which another young writer, at least mildly acquainted with the “literary” world, might have suffered. But Red Cloud, like any other place, had its hierarchy of name, wealth, and manners, and Cather’s early correspondence demonstrates that she was both attuned to it and respectful of it. Cather was a radical, but she remained a bourgeois radical, keeping the good manners with which she was brought up.

The form and meaning of Cather’s radicalism have been a source of scholarly debate, even discomfort. In style she was avant-garde, but her relation to American modernism was complex and at times even fraught. She claimed enormous personal freedom for herself, and in her writing she depicted the achievement of that freedom for women artists and what it cost them. But her cotton shirtwaist pressed against no barricades. For Cather, freedom was fundamentally an individual rather than a collective project. This stance has been unsatisfactory to some contemporary critics who would prefer to make of her a martyr-activist.

Cather’s letters of 1922 shed light on a difficult episode in her career, which came with the publication of her World War I novel, One of Ours, in which a Nebraska farm boy dies in the fields of France feeling that he has given his life “for an idea.” Cather’s rare anxiety about what she had written is confirmed here in a letter to H.L. Mencken, whose opinion she knew would be pivotal to the book’s reception. The novel, she told Mencken, was one young man’s story, and only that, and should not be read as standing for the experience of an entire generation that went to the trenches. Cather well knew that the prevailing narrative of the war among writers who saw action at the front was otherwise. Mencken, Hemingway, and others savaged One of Ours as the work of a genteel lady novelist, and the book remains one of Cather’s least admired, defended only for its early scenes set in her familiar Nebraska.

Cather’s letters of 1922 shed light on a difficult episode in her career, which came with the publication of her World War I novel, One of Ours, in which a Nebraska farm boy dies in the fields of France feeling that he has given his life “for an idea.” Cather’s rare anxiety about what she had written is confirmed here in a letter to H.L. Mencken, whose opinion she knew would be pivotal to the book’s reception. The novel, she told Mencken, was one young man’s story, and only that, and should not be read as standing for the experience of an entire generation that went to the trenches. Cather well knew that the prevailing narrative of the war among writers who saw action at the front was otherwise. Mencken, Hemingway, and others savaged One of Ours as the work of a genteel lady novelist, and the book remains one of Cather’s least admired, defended only for its early scenes set in her familiar Nebraska.

From the beginning Cather conceived of her artistic project as that of recording the history of a vanishing way of life, a life that once gone would be gone forever. She set herself up very early as a spiritual archivist of sorts, and her work is full of omens of decline and obsolescence. Even a spiritually resolute novel like Death Comes For The Archbishop is suffused with sadness for something lost.

From the beginning Cather conceived of her artistic project as that of recording the history of a vanishing way of life, a life that once gone would be gone forever. She set herself up very early as a spiritual archivist of sorts, and her work is full of omens of decline and obsolescence. Even a spiritually resolute novel like Death Comes For The Archbishop is suffused with sadness for something lost.

Yet Cather is the least sentimental of artists.

One of her most striking scenes comes in My Antonia when a hobo commits suicide by throwing himself into a grain thresher. The thresher, a potent symbol of the coming machine society, makes of the hobo what the values of that society would do to the Bohemian farmers of Cather’s youth. If the crucial inflection point of modernity for the next generation of writers was the war, for Cather that point came somewhat earlier, as the farmer’s relation to the land was changed by mechanization and commercialization in the 1890s.

Reading these letters is satisfying in that they tend to confirm our basic sense of Cather as an artist and a consciousness. The “Aunt Willie” of later years is the same woman who wrote O Pioneers! and The Professor’s House. An integrated and abundantly healthy personality is at hand. This is not say, of course, that Cather lived an entirely happy life. The end for her was lonely, as it is for most people. She perhaps felt that she had received somewhat less than her due, as most of us feel at one time or another. But she had her life, as many of us never do, and against considerable odds.

Reading these letters is satisfying in that they tend to confirm our basic sense of Cather as an artist and a consciousness. The “Aunt Willie” of later years is the same woman who wrote O Pioneers! and The Professor’s House. An integrated and abundantly healthy personality is at hand. This is not say, of course, that Cather lived an entirely happy life. The end for her was lonely, as it is for most people. She perhaps felt that she had received somewhat less than her due, as most of us feel at one time or another. But she had her life, as many of us never do, and against considerable odds.

Cather was not a modest woman. She knew very well what she was and saw no reason to dissemble. But she was also content to let her work speak for itself. This is another sense in which she speaks to us across a large cultural divide. She preceded the age of publicity, and the idea that the personal is political would have seemed to her both foolish and naïve. She died a New Yorker and a devotee of the Metropolitan Opera, but her values were always those of yeomanry, of Red Cloud. Like well-made furniture, her novels strengthen with age, taking on the character of their absent maker. Her reputation is not the largest in American letters, but at this moment it appears to be one of the sturdiest.