When I was 10 years old, there was a song I could not stop singing, and that I very much wished that I could. It was “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” by The Beatles, the third track on the first side of their 1969 album, Abbey Road. Though the melody of the song has a catchiness that made it attractive to me, the lyric has a darkness that made it dreadful. The melody wears short trousers and the lyric wears long. And that lyric, about a murderer, messed me up. There came upon me, not rationally but massively, the conviction that if I continued to sing this song then my parents would die. And yet I could not stop singing it. There I would be, walking blithely through the house, or walking blithely across the garden, and then realize that for the last few seconds, I had, yet again, been singing of Maxwell Edison and his homicidal hammer, and a great dread would invade me, because it meant, this singing, the removal of my parents from the world. This was a laughable idea, of course. But that an idea is laughable isn’t much of a bar to its presence in the human mind, is only patchily the occasion of laughter. I, certainly, wasn’t doing any laughing. The song became, for me, a thing of unmanning malignity, a breach through which the worst of all facts could have at me, through which the thoughts I most wanted kept out crashed in. I knew it, this song, as an ambush. It was a thing by which, at any time of day, I could be undone.

When I was 10 years old, there was a song I could not stop singing, and that I very much wished that I could. It was “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” by The Beatles, the third track on the first side of their 1969 album, Abbey Road. Though the melody of the song has a catchiness that made it attractive to me, the lyric has a darkness that made it dreadful. The melody wears short trousers and the lyric wears long. And that lyric, about a murderer, messed me up. There came upon me, not rationally but massively, the conviction that if I continued to sing this song then my parents would die. And yet I could not stop singing it. There I would be, walking blithely through the house, or walking blithely across the garden, and then realize that for the last few seconds, I had, yet again, been singing of Maxwell Edison and his homicidal hammer, and a great dread would invade me, because it meant, this singing, the removal of my parents from the world. This was a laughable idea, of course. But that an idea is laughable isn’t much of a bar to its presence in the human mind, is only patchily the occasion of laughter. I, certainly, wasn’t doing any laughing. The song became, for me, a thing of unmanning malignity, a breach through which the worst of all facts could have at me, through which the thoughts I most wanted kept out crashed in. I knew it, this song, as an ambush. It was a thing by which, at any time of day, I could be undone.

It is not amongst the most loved of The Beatles’ songs, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” Ian MacDonald, in Revolution in the Head, his celebrated disquisition on The Beatles’ discography, describes this McCartney composition as a “ghastly miscalculation” and as “sniggering nonsense” and claims it was a song that Lennon despised. The tale of a murderous medical student, it has a jarringly jaunty tune — a Trojan tune that smuggled the horrific into my head. The song I discovered when investigating my parents’ record collection, a discovery as unfortunate as that of some cursed amulet that brings woe to its owner, but of which the owner can never be rid. But Abbey Road is, despite “Maxwell,” the Beatles album that means the most to me, perhaps, in part, because I knew it when I was young, and it has the additional import, therefore, of a lost thing found, or of a thing delivered from afar. Whatever makes a rock from the Moon matter more than a rock from your garden — that ingredient is present, I find, in the things first known. But the album, of course, requires no biographical happenstance on the part of the listener to have meaning. Good things are to be found therein. Including the moment, during the second side’s long medley, when the briskness of “Polythene Pam” gives way to the lengthier phrasing of “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window,” and the moment of changed pace feels like the moment a glider is freed from the plane that pulls it, the brutish motoring left behind in a rapturous banishing of racket and rush. Yet for all that is good on the album, it is what is bad that remains, for me, most potent. There was a long period of my life when even the sight of the third track’s title on the back of the sleeve was a cause of disquiet. And though I know that I will have to listen to the track again for the writing of this essay, I am now at the end of the second paragraph and have yet to get the listening done.

It is not amongst the most loved of The Beatles’ songs, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” Ian MacDonald, in Revolution in the Head, his celebrated disquisition on The Beatles’ discography, describes this McCartney composition as a “ghastly miscalculation” and as “sniggering nonsense” and claims it was a song that Lennon despised. The tale of a murderous medical student, it has a jarringly jaunty tune — a Trojan tune that smuggled the horrific into my head. The song I discovered when investigating my parents’ record collection, a discovery as unfortunate as that of some cursed amulet that brings woe to its owner, but of which the owner can never be rid. But Abbey Road is, despite “Maxwell,” the Beatles album that means the most to me, perhaps, in part, because I knew it when I was young, and it has the additional import, therefore, of a lost thing found, or of a thing delivered from afar. Whatever makes a rock from the Moon matter more than a rock from your garden — that ingredient is present, I find, in the things first known. But the album, of course, requires no biographical happenstance on the part of the listener to have meaning. Good things are to be found therein. Including the moment, during the second side’s long medley, when the briskness of “Polythene Pam” gives way to the lengthier phrasing of “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window,” and the moment of changed pace feels like the moment a glider is freed from the plane that pulls it, the brutish motoring left behind in a rapturous banishing of racket and rush. Yet for all that is good on the album, it is what is bad that remains, for me, most potent. There was a long period of my life when even the sight of the third track’s title on the back of the sleeve was a cause of disquiet. And though I know that I will have to listen to the track again for the writing of this essay, I am now at the end of the second paragraph and have yet to get the listening done.

It was not the only piece of music, this, that snared me with its melody and disturbed me with its words. There was also Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, which, I think, was the first record I ever owned. The five- or six-year-old me sent away a certain number of labels from bottles of Ribena, and received, in return, a copy of Peter and the Wolf on flexi-disc. I found it magically pretty, this piece of music. It seemed to me extraordinary that something so pretty could exist, and be in my possession. Here was gorgeousness caught, as baffling a capture as a snatched sunbeam or a phantom filmed. And yet I found listening to it an ordeal. Because the narration was about a cat, a bird, and a duck being hunted by a wolf, and, in the case of the duck, eaten. Which I did not like. The chasing of the cat made me afraid, I remember, for my own cat, who seemed to me very meaningful, and, as I listened to the narration, very vulnerable. The narration, as it happens, has a cushioned conclusion, pulls back, at the last, from an adult frankness about death — Peter persuades the hunters not to kill the wolf but to take it to the zoo, and as the wolf is led away we hear the duck it has eaten quacking from inside its stomach. This is mortality fashioned with a child in mind, mortality tailored to the tender. Nevertheless, the tale bothered me, and quite soon the mortality proved more worrying than the melody was alluring, and I put the record safely to one side. But with “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” the record could not be put safely to one side. Because I couldn’t stop singing it.

It was not the only piece of music, this, that snared me with its melody and disturbed me with its words. There was also Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, which, I think, was the first record I ever owned. The five- or six-year-old me sent away a certain number of labels from bottles of Ribena, and received, in return, a copy of Peter and the Wolf on flexi-disc. I found it magically pretty, this piece of music. It seemed to me extraordinary that something so pretty could exist, and be in my possession. Here was gorgeousness caught, as baffling a capture as a snatched sunbeam or a phantom filmed. And yet I found listening to it an ordeal. Because the narration was about a cat, a bird, and a duck being hunted by a wolf, and, in the case of the duck, eaten. Which I did not like. The chasing of the cat made me afraid, I remember, for my own cat, who seemed to me very meaningful, and, as I listened to the narration, very vulnerable. The narration, as it happens, has a cushioned conclusion, pulls back, at the last, from an adult frankness about death — Peter persuades the hunters not to kill the wolf but to take it to the zoo, and as the wolf is led away we hear the duck it has eaten quacking from inside its stomach. This is mortality fashioned with a child in mind, mortality tailored to the tender. Nevertheless, the tale bothered me, and quite soon the mortality proved more worrying than the melody was alluring, and I put the record safely to one side. But with “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” the record could not be put safely to one side. Because I couldn’t stop singing it.

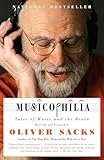

They are hardly strangers to each other, music and compulsion. The phenomenon of the earworm, of the tune that refuses to leave you be, has been much remarked. Oliver Sacks, in Musicophilia, his book on neurological oddities relating to music, describes people prey for long periods to the irresistible mental repetition of a tune, and quotes a correspondent who suggests that the cause lies in our hunter-gatherer past, when learning the sounds of wildlife through repetition would have been of assistance to survival. With me, the repetition was not mental but vocal. I was given to unbidden singing, sometimes to the annoyance and amusement of those around me, and can remember the day, in my early 20s, when I managed to leave such singing behind, my work colleagues giggling as I repeatedly started to sing and then, on each occasion, immediately stopped and apologized, and, over a couple of hours, brought the automatism finally to a halt. It’s no accident that music, which can so unevictably inhabit us, is often depicted as magic. In the fairy tale, “Roland,” the title character rids himself of a witch by playing her a magic tune on his fiddle. The witch cannot stop dancing and eventually dances herself to death. In “The Wonderful Musician,” a lonely fiddler seeks to attract a companion with his playing, and a woodcutter, hearing this playing, leaves his work in spite of himself and stands and listens to the fiddler as if enchanted. Sometimes what music means is that our will is neither here nor there, and my will, when I was 10, was exactly that. I was in the grip of a ghastly enchantment, and did not have what was necessary to get myself free of that grip.

They are hardly strangers to each other, music and compulsion. The phenomenon of the earworm, of the tune that refuses to leave you be, has been much remarked. Oliver Sacks, in Musicophilia, his book on neurological oddities relating to music, describes people prey for long periods to the irresistible mental repetition of a tune, and quotes a correspondent who suggests that the cause lies in our hunter-gatherer past, when learning the sounds of wildlife through repetition would have been of assistance to survival. With me, the repetition was not mental but vocal. I was given to unbidden singing, sometimes to the annoyance and amusement of those around me, and can remember the day, in my early 20s, when I managed to leave such singing behind, my work colleagues giggling as I repeatedly started to sing and then, on each occasion, immediately stopped and apologized, and, over a couple of hours, brought the automatism finally to a halt. It’s no accident that music, which can so unevictably inhabit us, is often depicted as magic. In the fairy tale, “Roland,” the title character rids himself of a witch by playing her a magic tune on his fiddle. The witch cannot stop dancing and eventually dances herself to death. In “The Wonderful Musician,” a lonely fiddler seeks to attract a companion with his playing, and a woodcutter, hearing this playing, leaves his work in spite of himself and stands and listens to the fiddler as if enchanted. Sometimes what music means is that our will is neither here nor there, and my will, when I was 10, was exactly that. I was in the grip of a ghastly enchantment, and did not have what was necessary to get myself free of that grip.

So yes, what I thought, when I was 10, was this: that as a consequence of my singing “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” — my monstrously involuntary singing of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” — my parents would die. But not immediately. In three years’ time. When I would be 13 and they would be 42. There seemed to me a fatal conjunction in those numbers. Because both were inauspicious. Thirteen traditionally so. And 42 because that was the age at which Denis, the man who lived opposite, had died. Denis had two children who were much the same age as my sister and me. And yet, somehow, this hadn’t stopped him dying. Denis’s death, I now suspect, had much to do with my troubles. If he could die, I had realized, then my parents could too. I would have known this already, of course. But his death gave the knowledge heft. That those who were the land you lived in could be lost to you, that the ones where all the warmth was could be removed — Denis’s death had flicked a switch and made this knowledge live. And my anxiety about it, I am speculating, infected my singing of the song. There was a reason, I think, why it was this particular song that was a problem, and not another. It was because my singing of this song seemed a transgression. It was about a murderer bringing a hammer down upon people’s heads. It was not a song, I felt, that I should have been singing. Yet sing it I did. I was a 10-year-old much given to toeing the line, and yet there I was, guilty, unarrestably, of transgression. And bad things are born of transgression. Just as Adam and Eve, in their consumption of the forbidden fruit, had brought mortality upon the race, so was I, in my singing of a forbidden song, bringing mortality upon my mother and father. I was doing wrong and the horrible would follow. And yet I couldn’t stop. I could not.

Here we are now, six paragraphs in, and still I haven’t steeled myself to listen again to the song. I have, over the years, listened to it on several occasions, and without any significant psychological collapse. But I am finding the notion onerous now. Not because I fear a resumption of the compulsion. Or because I fear that to hear it will spell my parents’ end. I am long rid of such thinking, and will walk under the unluckiest of ladders with wild abandon. Nevertheless, I was in the habit of hating it, and the habit has made a partial return, though I know that there is nothing there to hate. That a prejudice has been debunked can be of strangely little impediment to the persistence of that prejudice. I used to recoil, for example, at the thought of watching a western, and decided to watch half a dozen to confront my prejudice and make larger the likeable world. And I did, indeed, find that I liked them, and felt the prejudice depart. And then, as time passed and I went a while without watching another, I felt the prejudice grow back, in peculiar heedlessness of experience. “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” is not, I know, a thing of nasty magic, yet an odor of nasty magic remains. Yes, there that odor is. Some art we have to be feeling strong to consume, and some art we have to be feeling weak. But that there exists a piece of music that has a strange power over me — I do not entirely dislike this idea. I am apt to be grateful for the strange, for that to which my thinking might gainfully go. And that it’s possible to create a piece of art that plays havoc with a human — this idea can do gingering things to a writer, as can all evidence that art is not a thing inert. That it might be possible to summon something of similar import, a sentence or a story that does not pass traceless through the soul — this makes one hasten to the waiting page far wider of pupil.

It is right, I think, to talk now of the Yorkshire Ripper. For the Yorkshire Ripper, I suspect, may be pertinent. I was, as a child, particularly given to nocturnal fears, and there was a period when I would spend large parts of each night leaning out of bed in stricken vigilance, monitoring the stairs for the Yorkshire Ripper’s ascent. The face of this murderous inadequate I knew from the front page of my parents’ paper, which meant that he was, by this time, safely in custody. And in his long and sanguinary career he had shown no interest whatsoever in butchering small boys. But my fear of him was a thing to which the facts had no access. And it wasn’t only for myself that I feared. My parents’ room stood between mine and the top of the stairs, and I would weigh in my mind whether this was a cause of comfort or concern, whether my parents provided a bulwark against the awful or would in fact be the first things the awful fell upon. I wasn’t clear what powers my parents had. It was possible murderers had more. I once, when young, raised the question of my parents dying with my mother, and she laughed, and declared that that was a long, long time away and wasn’t something I had to worry about. But when I was 10, I was worried. At the thought of being alone in the world, and with less strength than the world required. When I think, now, of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” I think also of the Yorkshire Ripper. They overlap in my mind. Let me look up the dates. I have looked up the dates. They match. I was bedevilled by the one at the same time as I was bedevilled by the other. But my fears about both petered out. By the time I was 13 and my parents were 42 and the fatal conjunction of the numbers was in place, my compulsive singing of the song had ceased, along with my fear, and the year reached its end without the augured apocalypse coming to pass.

Now, I suppose, I must behave like an adult, and listen again to the song. That plaguing perkiness. That bright-eyed blight. I am not without hopes that this will induce in me some enormous meltdown so as to give the final paragraph some pizzazz. If the listening were to coincide with terrible news about my parents, what weight the final paragraph would have. The writing of that last sentence caused me some unease. I felt the errancy in it imperilling my parents. I felt the infraction in it doing something damning. It does not confine itself entirely to one’s childhood, does it, the childish mind. But here we go then. Here we go.

I am back and I am, of course, unharrowed. Nothing terrible was triggered. None of the odious potency remained. “When the fear yields,” wrote Saul Bellow, in Henderson the Rain King, “a beauty is disclosed in its place.” It would be pushing it, perhaps, to categorize “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” as a thing of beauty. But I did not dislike it. There was McCartney’s light voice taking a pleasant melody over the oompah underpinnings, and the lyric that fell so foul on my infant self fell utterly fallow on my adult. There was nothing there to induce upheaval. The only element of the track that caught on me was to be found during the final verse, a very quiet organ line that I have never noticed before, a thing muted enough to be mysterious, lying there beneath the more obvious elements of the orchestration, and the hiddenness of which passed, to my ears, for profundity. I want to listen to that again.

I am back and I am, of course, unharrowed. Nothing terrible was triggered. None of the odious potency remained. “When the fear yields,” wrote Saul Bellow, in Henderson the Rain King, “a beauty is disclosed in its place.” It would be pushing it, perhaps, to categorize “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” as a thing of beauty. But I did not dislike it. There was McCartney’s light voice taking a pleasant melody over the oompah underpinnings, and the lyric that fell so foul on my infant self fell utterly fallow on my adult. There was nothing there to induce upheaval. The only element of the track that caught on me was to be found during the final verse, a very quiet organ line that I have never noticed before, a thing muted enough to be mysterious, lying there beneath the more obvious elements of the orchestration, and the hiddenness of which passed, to my ears, for profundity. I want to listen to that again.

Instead, however, I have just listened to a version of the song by Jessica Mitford, a larky version in which she pays but scant obeisance to the tune, her elderly voice plonking down on the notes with jolly imprecision, her ineptitude so blithe that one starts to think it admirable. The original, though far less slapdash, is larky too. There is a point, during the verse in which Maxwell dispatches his teacher, when McCartney has to conquer an inclination to laugh. And the bassline, in its amiability, would suit a humorous tuba. A tuba wasn’t used. But it’s a song — and I realize how grave a statement this is — that teeters on the brink of using a tuba. He has said, McCartney, that for him the song embodies the fact that bad things can happen out of the blue. That isn’t a reading of the song I would ever have arrived at. Because it isn’t about terrible things happening to one person. It’s about one person doing terrible things. Nevertheless, when I was 10, the song did, for me, embody the worst blow a person could know, and I think perhaps I experienced the light treatment of dark matters not as an attempt to draw the sting of such matters – or whatever it is one is doing when one deals depthlessly with death — but as a violation I would be punished for being privy to.

I am not so strange, I suspect, in having once thought a tune taboo, in having thought myself the font of the horrible, my trespasses the murderers of my parents. Magical thinking, I have just read, in a culpably tardy session with a search engine, is particularly common amongst children, especially with regard to death. They are apt to blame themselves for a death, to think that what’s at the root of it is their wretchedness. In the film, MirrorMask, written by Neil Gaiman, which has just shown, with kindly timing, on TV, the young protagonist, while throwing an adolescent tantrum, wishes her mother dead, and then, when her mother falls ill soon after, thinks her wish the culprit. That the meaningful are mortal — a large part of human oddness is born of this fact. Wherever the meaningful are mortal, oddness will follow. As prevention or as explanation or as solace. Though guilt about the dead, of course, isn’t always groundless. They die, the loved, and then there is guilt. Because we will not always have lived up to the fact that they mattered. But the situation, when I was 10, was this — I was a child faced with an adult fact, and childishness followed. Perhaps, buried somewhere within my thinking, was the notion that if my parents’ dying was down to me, then I could, by being good, make them immortal. To think death the consequence of sin is to think death defeatable. Because we can stop being sinful. But I, for a long while, couldn’t stop. My tongue would make the decision to sing, and there I would be, up to my neck in the terrible. I think about singing it now, the opening line of the song. But I only think about it. No, that won’t do. I shall sing it. I have sung it. But quietly. I didn’t exactly belt the thing out.

I am not so strange, I suspect, in having once thought a tune taboo, in having thought myself the font of the horrible, my trespasses the murderers of my parents. Magical thinking, I have just read, in a culpably tardy session with a search engine, is particularly common amongst children, especially with regard to death. They are apt to blame themselves for a death, to think that what’s at the root of it is their wretchedness. In the film, MirrorMask, written by Neil Gaiman, which has just shown, with kindly timing, on TV, the young protagonist, while throwing an adolescent tantrum, wishes her mother dead, and then, when her mother falls ill soon after, thinks her wish the culprit. That the meaningful are mortal — a large part of human oddness is born of this fact. Wherever the meaningful are mortal, oddness will follow. As prevention or as explanation or as solace. Though guilt about the dead, of course, isn’t always groundless. They die, the loved, and then there is guilt. Because we will not always have lived up to the fact that they mattered. But the situation, when I was 10, was this — I was a child faced with an adult fact, and childishness followed. Perhaps, buried somewhere within my thinking, was the notion that if my parents’ dying was down to me, then I could, by being good, make them immortal. To think death the consequence of sin is to think death defeatable. Because we can stop being sinful. But I, for a long while, couldn’t stop. My tongue would make the decision to sing, and there I would be, up to my neck in the terrible. I think about singing it now, the opening line of the song. But I only think about it. No, that won’t do. I shall sing it. I have sung it. But quietly. I didn’t exactly belt the thing out.