Henry Miller’s boyhood home at 662 Driggs Ave. in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Henry Miller’s boyhood home at 662 Driggs Ave. in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

“The foam was on the lager.”

Now that Brooklyn is, by acclamation, the coolest place in the universe, it’s fitting that one of the borough’s literary lions is enjoying a week in the spotlight. The Big Sur Brooklyn Bridge Festival, which runs until Sunday, May 19, is a week-long celebration of the life and writing of native son Henry Miller, who spent the first years of his life in Williamsburg, in a three-story apartment building that’s still standing at 662 Driggs Ave. The Miller family occupied the top floor from 1892, the year after Henry’s birth, until 1900, when the respectable German-American Millers moved further inland to Bushwick to get away from the new arrivals pouring across the river from Manhattan, mostly Italians and Jews.

Today the 600 block of Driggs Avenue carries only faint echoes of Miller’s boyhood. No plaque commemorates his time there. Haberman’s noisy tin factory behind the apartment building is long gone. So are the tailor shop and veterinarian’s office across the street, and Pat McCarren’s saloon at the corner, where young Henry was sent to fetch pitchers of beer whenever relatives visited. “The foam was on the lager,” as Miller later wrote about the Williamsburg of his youth, “and people stopped to chat with one another.”

That world is gone, but no matter. Miller’s spirit still hovers over the streets of Williamsburg, which is why it was chosen as the site for this week’s festival by the Henry Miller Memorial Library of Big Sur, Calif., where Miller lived from the 1940’s until the mid-1960s, after his long-banned masterpiece, Tropic of Cancer, was finally published in the U.S. The Supreme Court eventually ruled that the novel was not obscene and could no longer be banned. Nearly a half-century after that historic ruling, the Big Sur Brooklyn Bridge Festival has a pop-up bookstore in Williamsburg featuring Miller manuscripts, letters, watercolors, and first editions; there are also panel discussions, readings, and comedy and musical performances.

That world is gone, but no matter. Miller’s spirit still hovers over the streets of Williamsburg, which is why it was chosen as the site for this week’s festival by the Henry Miller Memorial Library of Big Sur, Calif., where Miller lived from the 1940’s until the mid-1960s, after his long-banned masterpiece, Tropic of Cancer, was finally published in the U.S. The Supreme Court eventually ruled that the novel was not obscene and could no longer be banned. Nearly a half-century after that historic ruling, the Big Sur Brooklyn Bridge Festival has a pop-up bookstore in Williamsburg featuring Miller manuscripts, letters, watercolors, and first editions; there are also panel discussions, readings, and comedy and musical performances.

All of it made me stop and wonder: Does Henry Miller deserve such fuss?

“A life without hope, but no despair.”

Like many avid, life-long readers – particularly those of the American male persuasion – I went through a Henry Miller phase. Mine started late, after the peak of Miller’s fame and notoriety in the 1960s and ’70s. But my Miller phase proved to be more protracted and intense than most.

It started, appropriately enough, in Paris, where I had gone to live in 1979 because I’d fallen in love with a woman who was in school there and I thought it would be a fine place to finish writing an apprentice novel I’d been working on for several years. I was a walking cliche! – an American in Paris, suffering gorgeously, trying to write the great American novel in a seedy top-floor apartment that could fairly be called a garret. The whole thing was a fiasco. The writing wasn’t going well and I was constantly worried about money. One raw winter day, feeling utterly defeated, I knocked off work early, drew a hot bath, and slipped into the tub with a book chosen at random from the stack on the coffee table. It was Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller, a book I had somehow managed to miss during the high season of the sexual revolution. Reading the opening lines was like sticking my finger into a wall socket:

I am living at the Villa Borghese. There is not a crumb of dirt anywhere, nor a chair misplaced. We are all alone here and we are dead.

Last night Boris discovered that he was lousy. I had to shave his armpits and even then the itching did not stop. How can one get lousy in a beautiful place like this? But no matter. We might never have known each other so intimately, Boris and I, had it not been for the lice.

Boris has just given me a summary of his views. He is a weather prophet. The weather will continue bad, he says. There will be more calamities, more death, more despair. Not the slightest indication of a change anywhere. The cancer of time is eating us away. Our heroes have killed themselves, or are killing themselves. The hero, then, is not Time, but Timelessness. We must get in step, a lock step, toward the prison of death. There is no escape. The weather will not change.

It is now fall of my second year in Paris. I was sent here for a reason I have not yet been able to fathom.

I have no money, no resources, no hope. I am the happiest man alive. A year ago, six months ago, I thought I was an artist. I no longer think about it. I am.

What the fuck was this? I couldn’t say for sure. All I knew was that I had stumbled onto writing that was unlike anything I had ever read before, writing that spoke directly, almost weirdly, to my predicament, writing that had no use for plot, drama, foreshadowing, character development – all the writerly tricks that marked the “serious” fiction I’d been reading all my life. Instead of a conventional hero, there was just this American nobody shambling around the shabby back streets of Paris in the 1930s, dead broke, cadging money and drinks and meals and sex. The book’s second page hinted at what I was in for:

This then? This is not a book. This is libel, slander, defamation of character. This is not a book, in an ordinary sense of the word. No, this is a prolonged insult, a gob of spit in the face of Art, a kick in the pants to God, Man, Destiny, Time, Love, Beauty….

I couldn’t stop reading. The language was bewitching, a wised-up slang Miller picked up on the streets of Brooklyn and then burnished to a ribald, hallucinatory glow. Wherever he goes, Miller’s protagonist, known only as Joe, encounters a gallery of colorful misfits. They have false teeth and halitosis, their hands sweat, they fret about syphilis and lice and the clap. They visit “joints” and “dives” and pour out rivers of “flapdoodle” and “flummery.” They’re a bunch of “butter-tongued bastards” who “fulminate” and “bombinate” and “cluck like a pygmy.” Every now and then they “throw a fuck” into a “cunt.” The sex – the thing that would make Miller famous, to his undying chagrin – is graphic, ubiquitous, usually casual (or paid for up front), and frequently hilarious. One day Joe agrees to take a distinguished Hindu visitor to a whorehouse, where the guest, unfamiliar with French plumbing, proceeds to drop a pair of “enormous turds” in the bidet. The girls and the madam are horrified. Pandemonium ensues.

But those two turds lead Joe to a liberating epiphany about the utter hopelessness of human life:

Somehow the realization that nothing was to be hoped for had a salutary effect upon me. For weeks and months, for years, in fact, all my life I had been looking forward to something happening, some extrinsic event that would alter my life, and now suddenly, inspired by the absolute hopelessness of everything, I felt relieved, felt as though a great burden had been lifted from my shoulders… I made up my mind that I would hold on to nothing, that I would expect nothing, that henceforth I would live as an animal, a beast of prey, a rover, a plunderer.

A bit later he adds this refinement to the epiphany about the new world he has entered: “A world without hope, but no despair.”

In the end Miller, through his stand-in Joe, fulfills the promise of the book’s opening lines. He delivers that gob of spit in the eye of modern civilization and its empty promises to improve the human race. “The world is pooped out: there isn’t a dry fart left,” he declares. “Who that has a desperate, hungry eye can have the slightest regard for these existent governments, laws, codes, principles, ideals, ideas, totems, and taboos?” Delivering that gob of spit is an act of stupendous bravery because it requires a willingness to forego creature comforts and illusions and become a nobody. Better to be broke in Paris, Joe says, than to go back to America “to be put in double harness again, to work the treadmill.” It was this stance, as much as the writing itself, that turned me into a Henry Miller fan. Few possess his courage, his willingness to walk away from the American dream and embrace a life without hope. Fewer still manage to be what Miller claimed to be in the face of hopelessness – always merry and bright.

In the course of the next decade I would read every Miller title and interview I could get my hands on. But first I did something that would have appalled Miller: I pulled the plug on my failed Paris experiment and went back to America to work the treadmill, taking a job as a newspaper reporter in Norfolk, Va.

“Thomas Aquinas spoke here!”

Six months into the job, on the morning of Monday, June 9, 1980, I walked into the newsroom and learned that Henry Miller had died over the weekend in Pacific Palisades, Calif., at the age of 88. I felt a powerful need to write something about Miller for the next day’s paper, but I knew the skeptical city editor would demand a “local angle.” I paced and fretted. From what I knew, Miller had never set foot in that Virginia backwater. Then I remembered meeting Huntington Cairns, a writer and art critic who had worked at the Library of Congress for many years and was a long-time friend and supporter of Miller’s. Cairns was then living in retirement on the nearby Outer Banks. To my surprise, the city editor told me to go ahead and give Cairns a call. My story appeared in the next day’s paper under the stirring headline “Miller Is Extolled as Serious Artist.” It began:

Huntington Cairns, a citizen of the world who lives in Kitty Hawk, N.C., remembers walking to work in Washington years ago when an old friend approached.

It was Henry Miller, the writer.

“He said he wanted to go to a whorehouse,” Cairns recalled Monday. “I asked him what kind. He said he didn’t want to go to any ordinary one. He wanted to go where the senators went.”

Later in the article Cairns offers an assessment that I have come to agree with: Miller was a serious writer. He may not have been a great writer – in a league with Tolstoy – but he was an interesting writer and he was not writing pornography. He wanted the freedom to write his own view of the world as he saw it. And he was a hard-working man. He worked all day. He knew Paris like I know the palm of my own hand. We would pass a corner and he’d say, “Thomas Aquinas spoke here!”

A few years later I was working as a morning-drive disc jockey in Nashville and spending my free afternoons struggling to write a novel about a frustrated writer who’s working as a Nashville disc jockey and struggling to write a novel about his literary hero, Henry Miller. My phase was at its zenith. One day Miller, dead a half dozen years by then, walks into my fictional disc jockey’s apartment and strikes up a conversation, just like that. The two become fast friends. Pandemonium ensues.

My working title for the novel was The Colossus of Music City, a nod to The Colossus of Maroussi, still one of my favorite Miller books. One editor who turned down the manuscript wrote that my ghostly version of Miller “is certainly a lovable character – like a favorite uncle who drinks too much and whores around.” He may have been lovable, but not lovable enough. The novel failed to sell.

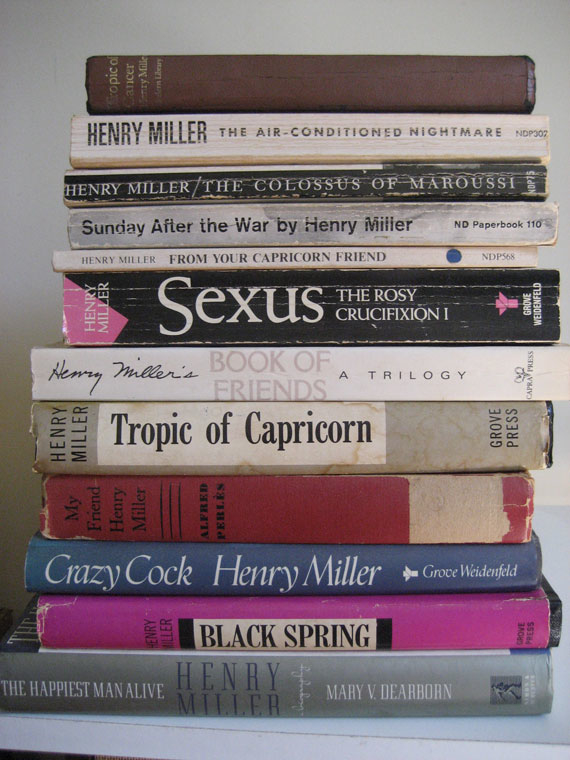

My own private Henry Miller Library.

My own private Henry Miller Library.

“The most boring businessman you can imagine.”

My Henry Miller phase began to fade after that. I’d read more than a dozen of his books – fiction and non-fiction, famous and obscure, wise and pedantic – before coming to the last straw, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare.

It was begun in 1941, after Miller had enjoyed a richly prolific decade. Tropic of Capricorn and Black Spring came steaming straight from the gutters of Brooklyn, Manhattan and Paris after Tropic of Cancer. Then it was on to Greece, where Miller wrote a sun-splashed ode to the sensuous life and a bon vivant named Katsimbalis. It is, along with Cancer, my favorite of Miller’s books. In Paris and Greece he was living off the cuff, far from his despised hometown and homeland, and as a result the writing was unfettered and full of joy.

It was begun in 1941, after Miller had enjoyed a richly prolific decade. Tropic of Capricorn and Black Spring came steaming straight from the gutters of Brooklyn, Manhattan and Paris after Tropic of Cancer. Then it was on to Greece, where Miller wrote a sun-splashed ode to the sensuous life and a bon vivant named Katsimbalis. It is, along with Cancer, my favorite of Miller’s books. In Paris and Greece he was living off the cuff, far from his despised hometown and homeland, and as a result the writing was unfettered and full of joy.

But Europe was sliding into the abyss and Miller narrowly slipped from under the gathering war clouds and returned, reluctantly, to the U.S. The gloom descended as soon as he boarded the American boat in Piraeus. “I was among the go-getters again,” he wrote, “among the restless souls who, not knowing how to live their own life, wish to change the world for everybody.”

After arriving in New York, he decides to take a cross-country road trip and record his impressions of a country he hasn’t seen in more than a decade. Face-to-face again with his countrymen, his guts get all wadded up and the writing becomes pinched and cranky. Worse, Miller makes the fatal mistake of buying into the claptrap that the artist is some sort of exalted figure, entitled to special treatment, immune to the rules and responsibilities that govern the rest of society:

Like every other big city in America New Orleans is full of starving or half-starved artists. The quarter which they inhabit is being steadily demolished and pulverized by the big guns of the vandals and barbarians from the industrial world… When the beautiful French Quarter is no more, when every link with the past is destroyed, there will be the clean, sterile office buildings, the hideous monuments and public buildings, the oil wells, the smokestacks, the air ports, the jails, the lunatic asylums, the charity hospitals, the bread lines, the gray shacks of the colored people, the bright tin lizzies, the stream-lined trains, the tinned food products, the drug stores, the Neon-lit shop windows to inspire the artist to paint. Or, what is more likely, persuade him to commit suicide.

The only thing missing from this unimaginative litany is cellophane.

Years after I read the book I learned that Miller had neglected to mention a telling encounter he had on his trip across the country. His editor in New York had arranged for him to visit Eudora Welty at her home in Jackson, Miss., and Miller took it upon himself to write her a letter in advance, letting her know that he could put her in touch with “an unfailing pornographic market” that paid a dollar a page. What would possess a man to make such an offer to a very proper Southern lady? I can only assume it was the bad boy’s eagerness to shock, to uphold the naughty reputation cemented by the still-banned but widely circulated Tropics books.

Whatever his reasoning, the visit to Jackson was a disaster and there is no mention of it in the book. As Welty later said, “We drove around in the family car. I took him all around. He was infinitely bored with everything.” After Miller left town, Welty called him “the most boring businessman you can imagine.” Businessman. Ouch.

“Must We Burn Henry Miller?”

A lot of women readers besides Eudora Welty have had trouble with Miller’s sexual candor, seeing it not as a badge of liberation but as the demeaning handiwork of a sexist at best, a misogynist at worst. By the time my Henry Miller phase came and went, he and his work had already been fed through the meat grinder by second-wave feminists, most notably Kate Millett in her 1970 book Sexual Politics, in which she castigates Miller along with D.H. Lawrence and Norman Mailer. “Miller is a compendium of American sexual neuroses,” Millett wrote, “and his value lies not in freeing us from such afflictions, but in having had the honesty to express and dramatize them.”

I agree. I suspect Miller agreed too. Erica Jong, author of the very Miller-esque novel Fear of Flying, definitely agrees. In an essay called “Must We Burn Henry Miller?” in her 1993 book The Devil at Large, Jong argues that Miller was not an enemy of women in general and feminists in particular. “Ultimately,” Jong writes, “Miller can be a stronger force for feminists than for male chauvinists. His writing consistently shows a ruthless honesty about the self, an honesty that even women writers would do well to emulate, because honesty is the beginning of all transformation.” Then Jong poses a rhetorical question to her fellow feminists: “Shall we burn Henry Miller? Better to emulate him. Better to follow his path from sexual madness to spiritual serenity, from bleeding maleness to an androgyny that fills the heart with light.”

I agree. I suspect Miller agreed too. Erica Jong, author of the very Miller-esque novel Fear of Flying, definitely agrees. In an essay called “Must We Burn Henry Miller?” in her 1993 book The Devil at Large, Jong argues that Miller was not an enemy of women in general and feminists in particular. “Ultimately,” Jong writes, “Miller can be a stronger force for feminists than for male chauvinists. His writing consistently shows a ruthless honesty about the self, an honesty that even women writers would do well to emulate, because honesty is the beginning of all transformation.” Then Jong poses a rhetorical question to her fellow feminists: “Shall we burn Henry Miller? Better to emulate him. Better to follow his path from sexual madness to spiritual serenity, from bleeding maleness to an androgyny that fills the heart with light.”

While Millett and Jong seem to have touched on the essence of Miller’s achievement and his worth, his place in the pantheon of American writers has never been fixed, which might be a good thing, something Miller himself would have approved of.

Steve Von, a psychoanalyst who will be part of a panel discussion at this week’s festival in Brooklyn, put it this way in an e-mail: “Henry Miller is a strange character in modern literature: both more and less popular than he seems. At first ignored, then outlawed, then celebrated, then forgotten, then remembered. He seems universally known, almost old hat, and yet he still has not been accepted by the academy.”

Now we’re getting close. Once so scandalous that he was outlawed, Miller is now old hat. How much the world has changed – and what a big part he played in changing it, for better and for worse.

Henry Miller did me several huge favors. He taught me that a novel can be whatever a novelist has the courage and the talent to conjure. He taught me that there’s something noble about stepping off the American treadmill, a lesson that’s more valuable today than ever before. He taught me that my native distaste for governments, authority, religions, taboos, cops, saviors, and salesmen puts me in good company.

Was Miller a great writer? I don’t know and I don’t care. He wrote one great book, a few very fine ones, a fair number of mediocrities and some outright junk. Not at all a bad life’s work for any writer. In the end, strange to say, the work matters less to me than the man who wrote it – or, more precisely, what that man had to go through to get it written. There, to me, lies greatness.

Images courtesy the author.