About halfway through the screening of the new documentary Herblock: The Black and the White, one of the closing entries in this year’s Tribeca Film Festival, it occurred to me that you haven’t really made it in America until someone has made a movie about you.

Three of the many talking heads in this documentary — reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, and former executive editor Ben Bradlee of The Washington Post — have already been the subjects of a movie, the much-praised 1976 feature film All the President’s Men, which was based on Woodward and Bernstein’s book about the fall of President Richard Nixon. What’s more, the actors who played the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporters in that movie — Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman — are the subjects of a new documentary about the making of the original feature film and the enduring fascination with Watergate. This new documentary is called, appropriately if unimaginatively, All the President’s Men Revisited. Stop the presses! Hollywood people never tire of talking about themselves and their achievements!

Three of the many talking heads in this documentary — reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, and former executive editor Ben Bradlee of The Washington Post — have already been the subjects of a movie, the much-praised 1976 feature film All the President’s Men, which was based on Woodward and Bernstein’s book about the fall of President Richard Nixon. What’s more, the actors who played the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporters in that movie — Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman — are the subjects of a new documentary about the making of the original feature film and the enduring fascination with Watergate. This new documentary is called, appropriately if unimaginatively, All the President’s Men Revisited. Stop the presses! Hollywood people never tire of talking about themselves and their achievements!

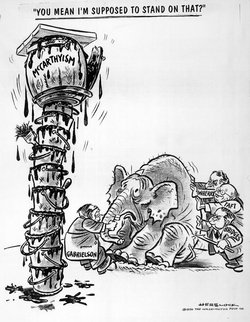

But back to Herblock. It’s a heartfelt, uplifting documentary about the legendary Washington Post cartoonist Herbert Lawrence Block, known universally by his nom de guerre, Herblock. Peppered with the predictable talking heads — though not Redford and Hoffman, mercifully — it tells the story of a self-effacing artist from Chicago whose patriotism, prescience, and deft pencil led American journalism’s charge against such bogeymen as Hitler (even before he was elected chancellor), the gun lobby, Sen. Joseph McCarthy, segregationists, big oil, big business, big military budgets, big money in politics (as early as 1950), the arms race, Stalin, the Vietnam War, and, most famously, Richard Nixon. Herblock drew McCarthy and Nixon with swarthy mugs, sweating, frequently crawling out of mud puddles or open sewer holes. Herblock coined the pejorative “McCarthyism,” and he hated Nixon’s guts and wasn’t shy about saying so. In our watered-down, fair-minded times, such venom is bracing.

In addition to all those talking heads, the documentary consists of many pictures of Herblock’s cartoons, interspersed with a long on-camera interview with him in his cluttered office at the Post. Dressed in his trademark baggy sweater, he comes across as a wise, witty uncle. “He worked until he died,” says one of the talking heads. Not quite. Herblock’s last cartoon appeared on Aug. 26, 2001, and he died six weeks later at 91, after working at the Post for 55 years and winning three Pulitzer Prizes, the Medal of Freedom, and an uncountable number of enemies among the rich, the powerful, and the corrupt.

In addition to all those talking heads, the documentary consists of many pictures of Herblock’s cartoons, interspersed with a long on-camera interview with him in his cluttered office at the Post. Dressed in his trademark baggy sweater, he comes across as a wise, witty uncle. “He worked until he died,” says one of the talking heads. Not quite. Herblock’s last cartoon appeared on Aug. 26, 2001, and he died six weeks later at 91, after working at the Post for 55 years and winning three Pulitzer Prizes, the Medal of Freedom, and an uncountable number of enemies among the rich, the powerful, and the corrupt.

The film makes the points that Herblock was always looking out for the little guy, that he was an ardent believer in the importance of a free press in a democracy, and that he enjoyed complete editorial freedom. This last point was not always the case. During the 1952 presidential campaign, the Post editorial board supported the Republican candidate, Dwight Eisenhower. Herblock drew scathing cartoons of Ike, portraying him as an out-of-touch lightweight. When the Post started pulling his anti-Eisenhower cartoons, readers howled — and pointed out that Herblock was syndicated in hundreds of other papers and they would take their business elsewhere. The Post editors caved in, and Herblock was forevermore off the leash.

After the Herblock screening ended and the applause died, the documentary’s director and co-writer, Michael Stevens, stepped onto the stage to answer questions. First he introduced several people in the audience who were involved in making the movie, including Alan Mandell, who, it turns out, is an actor who played Herblock in those interview scenes in Herblock’s office. This bit of legerdemain was jarring — I had assumed I was watching the real Herblock on the screen, not a convincing look-alike. Was it dishonest of Stevens to put words in the mouth of an actor in a documentary, without alerting the audience? And where did those words come from — the dozen books Herblock published in his lifetime? Interviews he gave? Stevens’s imagination? I raised my hand but never got to ask my questions.

[Editor’s Note: Filmmaker Michael Stevens has pointed out to us that this question is answered in the film’s credits, which state: “starring ALAN MANDELL as HERBERT BLOCK based on the writings and speeches of HERBERT BLOCK”]

As I headed home from the theater, those unsettling questions were crowded out of my mind by a memory. One of my most prized possessions is a photograph that was taken in The Washington Post newsroom on election night in 1952, when I was three months old and an out-of-touch lightweight named Dwight Eisenhower was in the process of defeating Adlai Stevenson for the presidency. The photograph depicts a scene of great hubbub — reporters crowding around a messy table full of old newspapers and sandwiches and coffee cups, while a man pours coffee from a big white hobo pot. It’s not hard to imagine the clatter of typewriters, the screaming of telephones, the distant murmur of a police radio, the cigarette smoke bluing the air. It’s a man’s world, and for me there is only one man in it: the guy pouring the coffee: my father.

I love the details of that photograph. The map of the world on the wall. The copy spike on the cluttered table. The milk in glass bottles. The lovingly wrapped sandwiches. The stacks of china cups and saucers. And, above all, my father’s patent-leather hair, his French cuffs, the dainty way he holds the coffee pot’s lid with his left pinkie as he pours for his fellow newsmen. That picture seems like an artifact from some prehistoric age.

My father was a respected Post reporter and rewrite man at the time — “the fastest typist in the newspaper business,” as Bradlee, then a hard-charging fellow reporter, would later put it in his memoir, A Good Life. (Upon reading those words in the 1990s, my father, a proud man, had sniffed, “I like to think I was the fastest writer in the newspaper business.”) Bradlee does not appear in that election-night photograph. Neither does Herblock, who had his own office down the hall. But the most noticeable absence, for me, was not the men who have now been immortalized by movies; it was an old-school police reporter named Alfred E. Lewis who worked on a series of articles with my father that nearly won a Pulitzer Prize. Lewis spent 50 years as a lowly cop reporter at the Post, nearly as long as Herblock, without acquiring a fraction of the cartoonist’s fame or fortune.

My father was a respected Post reporter and rewrite man at the time — “the fastest typist in the newspaper business,” as Bradlee, then a hard-charging fellow reporter, would later put it in his memoir, A Good Life. (Upon reading those words in the 1990s, my father, a proud man, had sniffed, “I like to think I was the fastest writer in the newspaper business.”) Bradlee does not appear in that election-night photograph. Neither does Herblock, who had his own office down the hall. But the most noticeable absence, for me, was not the men who have now been immortalized by movies; it was an old-school police reporter named Alfred E. Lewis who worked on a series of articles with my father that nearly won a Pulitzer Prize. Lewis spent 50 years as a lowly cop reporter at the Post, nearly as long as Herblock, without acquiring a fraction of the cartoonist’s fame or fortune.

The series my father and Lewis collaborated on was called “The Charmed Life of Emmett Warring,” about a powerful and slippery D.C. racketeer, a prime target in the Post’s campaign to root out police corruption. The articles ran on the front page every day for a week and jumped to two full inside pages, an astoundingly detailed and literary collaboration between a gumshoe street reporter and a lightning-fast rewrite man. Years later, after he had left the newspaper business, my father showed me a typed, single-spaced, two-page memo from his editor, spelling out the kind of detail he wanted in the series, right down to how many pairs of shoes Emmett Warring owned, what his house looked like, what brand of booze he drank, and how much of it. That memo is still astonishing to me — the realization that people cared so much and worked so hard at putting out a daily newspaper.

Bradlee, in his memoir, called Al Lewis “the prototypical police reporter, who had loved cops more than civilians for almost fifty years.” My father told me that Al Lewis had a hard time writing coherent English prose, but he knew every cop and every criminal in D.C., and he frequently beat the cops to the scene of a crime. In other words, he was an invaluable asset to the paper’s city desk. Twenty years after Ike’s victory, Lewis hadn’t lost a step.

On Sunday, June 18, 1972, the Post ran what appeared to be a routine breaking-and-entering story. It opened like this, straight, no frills:

5 Held in Plot to Bug Democrats’ Office Here

By Alfred E. Lewis, Post Staff Writer

Five men, one of whom said he is a former employee of the Central Intelligence Agency, were arrested at 2:30 a.m. yesterday in what authorities described as an elaborate plot to bug the offices of the Democratic National Committee here.

It turned out that when Lewis arrived at the Watergate complex with the acting police chief several hours after the bungled burglary, he sailed past the roped-off reporters outside the building and went right up to the crime scene, where he gathered vital color and details. Eight other reporters contributed legwork to Lewis’s report in that Sunday’s paper. One was a hungry young hun named Bob Woodward; another was “Peck’s bad boy,” in Bradlee’s words, a renegade named Carl Bernstein. At the time no one appreciated the story’s implications. But it’s a safe bet that the Post’s first Watergate story would not have had such punch and detail without the contacts and legwork of an old-school cop reporter named Al Lewis. And no one connected the mushrooming scandal’s dots more quickly than Herblock.

Herblock is a welcome reminder that there was a time, not so very long ago, when American newspapers were stocked with people like Herb Block and Al Lewis and Dick Morris, men and women who were passionate about producing quality journalism and didn’t give a thought to ratings, celebrity, blog hits, or search engine optimization. Today, even a superb investigative reporter like Bob Woodward has been neutered by the seductive fame and money that fester inside the Beltway. People in America are still producing quality journalism, but, like serious fiction, it is being pushed deeper and deeper into the margins of the culture by forces that seem unstoppable.

All the more reason to remember and celebrate faceless foot soldiers like Al Lewis. I say he deserves to be the subject of a documentary or feature film at least as much as the far more decorated Woodward and Bernstein and Bradlee and Herblock. I have a strong hunch that Herblock, that great champion of the unsung little guy, would have agreed with me.

Image Credits: Bill Morris and Wikipedia