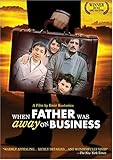

In the great Emir Kusturica film, While Father Was Away on Business, the young protagonist believes that when his father goes to work, the man simply leaves the house and stands in the garden for eight hours. It’s a marvelous detail that captures the egocentric nature of children’s thinking: How could my parents be doing something important if it doesn’t have to do with me? I work at home, and when my sons were young, I had the feeling that the film’s scenario was inverted, and that my children thought that I stood frozen inside the house while they were at school, only to be reanimated when they burst back through the door at the end of the day. Sure they knew I was a writer, but what did that actually mean to them? They were writers, too. They could form recognizable letters with a number two pencil, and increasingly, they could string those letters into words, albeit words “inventively” spelled. And the books they read or the ones I read to them? Yes, the title pages always said “by so and so,” but in the magical logic of children, these stories had always lived behind the covers of the books, just the way a tinny song exists in a music box even when you don’t open it, or the way that the cupboard can be counted on to contain at least one appealing snack, no trips to the grocery store required.

But, when my older boy was in the second grade, I found out that being a writer meant something very specific to him. One day, he brought home a calendar that he had made. As I turned the pages, I saw that a number of the pictures he had drawn to accompany the months — the particularly important months like June — the beginning of summer vacation — and December — Christmas, Hannukah, and his birthday — were all the same. Drawn with the waxy stutter of boldly colored crayons was a blond-headed woman with her back to the viewer sitting in a chair, staring at a computer.

I was taken aback. I made it a practice to work only when my kids were at school. When they were home, I played and cooked and listened and arbitrated, built pillow forts and Lego spaceships. But my son’s not-so-subtle message let me know that even if I were present, he was aware that some essential part of me existed only when I was working. He knew I had a secret.

I was taken aback. I made it a practice to work only when my kids were at school. When they were home, I played and cooked and listened and arbitrated, built pillow forts and Lego spaceships. But my son’s not-so-subtle message let me know that even if I were present, he was aware that some essential part of me existed only when I was working. He knew I had a secret.

And, of course, he was right. I do not spend a lot of time talking about my day-to-day work life with my children because, while I’m constructing a story or a novel, it is a secret. The process is a tremulous and amorphous one that often defies articulation, one that, for me, rarely benefits from being shared. In fact, the very private nature of my work is an essential ingredient. The isolation creates a necessary pressure that makes the writing necessary: I have to get it out so someone else can know about it. Speaking a story out loud before it is fully realized can release that pressure and obviate my need to actually set the story down on the page.

There are two modes to my working life — the actual keyboard to computer screen time, when words are parsed for specificity and nuance, and sentences are formed and refined, and the other less conscious but no less important work that happens by living life while an idea takes shape. So, I can play rounds of Candyland or, now that the kids are older, discuss college and life plans, and my subconscious will be teasing out a story problem. I don’t think I am any worse of a mother or a writer for the inextricable way the two parts of my life are joined, but I do recognize that my son was right those many years ago when he drew his calendar pictures: my focus is directed two ways — towards family and towards work. Occasionally one of my kids might ask “What is your book about?” As I formed some general description that would satisfy him while maintaining my idea’s anonymity, I would notice his attention drift away, not, I think, because of disinterest (although a story about wizards or exploding rockets might have engaged him more) but because that was not the question he meant to ask. It takes years for a child to come to fully understand that his parent is a completely separate being from him. And this question — what was this thing I did every day that so captivated me and that suggested my very individual life — was one he was not sure he wanted yet answered.

My sons are older now and each is immersed in a creative preoccupation of his own. Coincidentally, both are musicians, the older one is a drummer in a band, the younger one is immersed in classical music and composition and spends an enormous amount of time alone in a room with a piano and staff paper. If I were to draw a picture of them, it would be of the broadening back of a teenager leaning, Shroeder-like, over the keyboard, or a lean figure, face obscured by a curtain of hair, bent over a drum kit. We share a bit about process — about how frustrating it can be to settle down to a session of work and an hour or two hours later come out with little to show. I can let them know that I understand that creating something out of nothing is a lot like throwing a pot on a potter’s wheel. You raise up a form and then squash it back down, constructing and deconstructing your ideas over and over again until you begin to feel what the form should be. And I can urge them to stick with an idea no matter how wobbly it feels at first, because part of the creative problem is to put aside preconceived notions of what you want something to be and allow surprise and accident to take over. And I can remind them that a creative endeavor is not magic or kismet. It is a job of work, pure and simple. It is the hours playing drum figures over and over again. It is sitting down in front of that blank piece of staff paper and disciplining yourself to make marks on it.

But here’s the great irony: I want nothing more than to know what goes on in their heads while they are writing or performing music, not because I will ever understand why one chose a particular polyrhythm over another for a drum fill, or how the other imagines melodies, but because I want access to what I know is a highly emotional and deeply personal part of who they are. But I also realize that asking is about as inappropriate as trying to dig for information about their romantic lives. It’s none of my business. And it shouldn’t be. Because they deserve the same privacy that I demand for my work. Because I know that it doesn’t, in the end, do any good to talk about it.

A few years ago, I gave a reading of one of the stories from a new collection. My children were 17 and 14. They’d heard me read before, but I could tell that, for the first time, they were consciously aware that there were two Marisa’s in the room — their mother, who, they were sure, thought only about them and their needs and happiness, and this other Marisa, a person with feelings and ambitions and creative impulses that did not have a lot to do with them, or if they did, only obliquely. I looked up at them a few times while I was reading and I could sense their discomfort. They looked at all the people sitting and standing in the bookstore, perplexed that these people who didn’t know me as well as they knew me were concentrating so intently on what I had to say. And I could sense, too, that they weren’t sure how they were supposed to respond to my work. As my children? Or as objective listeners, free to judge and appreciate without those attitudes having any bearing on the foundation they relied on. I felt very protective of them at that moment, of their vulnerability. I wanted to stop reading and tell them not to worry, I was really only their mom. I wanted to assure them that they had been right all along: that when they went to school I simply stood in the living room until they arrived back home to give me purpose. I sped up my reading, hoping to get through the story faster in order to minimize any distress they might be experiencing. Finally, with relief, I came to the end of the piece. I was nearly out of breath and totally rattled. I wanted the night to be over as fast as possible, for the books to be signed, for me, my husband and my kids to get back in the car for the drive home. I wanted to hear them argue about radio stations and tell me that they were starving and did we have any fooooood? And then, I looked up from the book I was signing, and there they were, my boys, flanking me. My older son’s hand was on my shoulder. My younger son was looking shy and a little proud. They claimed me.

Image: Unsplash/Jade Seok.