Until the day the golfer spotted a dismembered head in the cool waters of Stony Brook, the scariest beast in Hopewell was the New Jersey Devil. As elementary school students, we were shown videos of the Devil rampaging flocks of sheep and terrorizing farmers in the Pine Barrens. This was frightening, to be sure, but the Pine Barrens were several hours by car southeast of Hopewell (pop. 2200) and the videos never showed the Devil’s face owing to budgeting constraints, as the filmmakers could not afford any special effects. Plus we had a professional hockey team named after him — the Devils — and they were an inspiration to young children, not a menace.

I remember receiving the news about the head late one night in a house in the Sourland Mountains in 1989. My friend George and I were locked in a fierce battle of Nintendo Ice Hockey, the chief variables of the game being to decide whether to choose a slow, plump player, who could shoot the puck hard and check anything in his path; a skinny player who was extremely lithe but who had a weak shot and could be easily bumped off his skates; or a medium-sized player who was a compromise between the other two body types. It was an addictive formula, and one that Nintendo continues to exploit in its games today. Anyway, we were engrossed in this battle when George’s parents mounted the stairs and solemnly told us that a severed head had been found in a creek by the Hopewell Valley Golf Club, and added that they had locked the doors and we’d been up late enough playing-your-games-and-you-should-get-some-sleep.

We did not sleep that night, of course. The thought of a head without its body was something that had never occurred to us, and we were old enough, about 10, to know that someone had killed this body before lopping off its head. We consoled ourselves, as our world views splintered and cracked, by watching The Ultimate Warrior thrash his opponents on the World Wrestling Federation until the sun pried open our dreary eyelids.

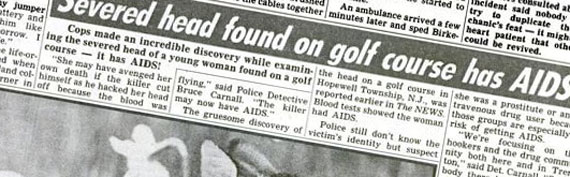

The local news followed the story of the severed head closely, and blood tests eventually revealed that it contained the AIDS virus. In 1989, AIDS was associated with two things, gays and blacks, and we believed you could contract it by cutting your head on metal and that the symptom was a long white hair on your tongue and throat. This only compounded our sense of terror: a dismembered head with a misunderstood virus.

The place where the head had been found was more bizarre, the seventh hole of an idyllic golf club. My family didn’t belong to the club, but I had been there with friends to swim in the pool, which had a deep-end colored a malevolent blue, so bottomless were its waters, and lifeguards that sneered as they twirled their whistles around their fingers. In my memories, the swimming pool is always sun-dappled and solar flared — enough to please J.J. Abrams — because we only went swimming on sunny days. Hopewell was a small town, and safe and complacent with its five churches, its family-owned deli, sport hunting shop, and pharmacy. It had once been a hotbed of the Ku Klux Klan, and before that a scene of fierce resistance during the Revolutionary War. Charles Lindbergh’s baby had been kidnapped from a second story window, and then discarded in the woods just outside town, but by the late 1980s Hopewell had become a desirable backwater with its ample green spaces, acres of woods, pristine creeks, Harvest Festival, and Memorial Day parade, where kids of all colors could roam freely without fear. We would ride our Huffies and Schwinns by the golf course, right over the spot where Stony Brook, the stream in which the head had been found, dipped beneath the road.

As time went on, and the head was never claimed, rumors began to circulate, and always seemed to end in one of two possibilities: the Mafia or a serial killer had done it. Serial killers were, of course, far scarier to a 10 year old than the Mafia. Unlike the Mafia, which (television had us believe) followed a moral code, serial killers were imbued with their own unique compass. As a kid, my main concern was to find out how many other killers were out there, because that would promote my survival. My parents reassured me that we were safe — what else could you say to a child about such a thing? — and I would believe them until the sun went down and our home filled with shadows. But there were deeper questions, too: Why hadn’t anyone noticed that a head was missing? Wasn’t the family looking for the head? The thought that no family member cared enough about this person’s head to claim it back was even more terrifying. If your family can’t search for your missing head, then what good are they, in the end?

Most of my questions about the head were fed by what my parents called “an active imagination,” but in hindsight the threats were never were too far away. While vacationing at my grandparents’ cabin in Wisconsin, my mom hid an ax under the bed because the bodies of slaughtered children had been turning up in the woods, before Jeffrey Dahmer had been caught; my best friend in Hopewell had once lived in Arkansas down the street from the mother of John Wayne Gacy, a serial killer who had apparently visited her regularly as my friend rode his bigwheel tricycle down the street.

Much later, working with asylum seekers in South Africa, I regularly met men and women from the Democratic Republic of Congo who fled war-torn areas where roving militias dismembered the bodies of civilian victims. The difference was that the practice was fed by a heady mix of psychotropic drugs, psychological warfare, and perverted interpretations of animist traditions. The scale of such murders was terrifying, but there were reasons in place. It was war and the militias feared the spirits of their victims. There was a certain logic.

As a Nigerian-American, I’ve also become accustomed to a few stereotypes, most of which revolve around Nigerian email scams, but also the selling of body parts. Not just internal organs, but arms, legs, feet, little fingers. (Just watch the South African film District 9, and you’ll see Nigerians who get off on dismembering people and also having sex with aliens from outerspace.) But again, there is a sort of reasoning to that illicit traffic. The bodies for these occult rituals are sliced apart for spiritual purposes, not as ends unto themselves.

As a Nigerian-American, I’ve also become accustomed to a few stereotypes, most of which revolve around Nigerian email scams, but also the selling of body parts. Not just internal organs, but arms, legs, feet, little fingers. (Just watch the South African film District 9, and you’ll see Nigerians who get off on dismembering people and also having sex with aliens from outerspace.) But again, there is a sort of reasoning to that illicit traffic. The bodies for these occult rituals are sliced apart for spiritual purposes, not as ends unto themselves.

Last week, after a 24-year search for more information about the head, the New Jersey State Police finally discovered the identity of the victim. She was a prostitute who had changed her name no less than 15 times, and she was identified by DNA tests that matched her with her aunt, who had filed a missing persons report with the police in 2001. Her name was Heidi Balch. She is believed to have been the first victim killed by Joel Rifkin, who confessed to murdering someone with the name of one of her aliases in 1993, and who had been sentenced to 200 years in prison after killing 17 prostitutes on a rampage. Rifkin claimed to have begun murdering prostitutes because he had contracted AIDS from one.

The HIV virus was the main character of South African author Kgebetli Moele’s 2009 novel The Book of the Dead, and the protagonist moved from victim to victim boasting of its conquests. It was not Moele’s best book — that would be Room 207, a must read — but it was chilling to read how the virus thrived on intimacy and broken relationships. Revenge was never the point of the virus in that story: it lived only for the sake of living. Rifkin, by contrast, claimed to be butchering for revenge and not for pleasure. In this, the fictional virus holds the moral upperhand, for it doesn’t pretend to be serving some larger purpose.

The HIV virus was the main character of South African author Kgebetli Moele’s 2009 novel The Book of the Dead, and the protagonist moved from victim to victim boasting of its conquests. It was not Moele’s best book — that would be Room 207, a must read — but it was chilling to read how the virus thrived on intimacy and broken relationships. Revenge was never the point of the virus in that story: it lived only for the sake of living. Rifkin, by contrast, claimed to be butchering for revenge and not for pleasure. In this, the fictional virus holds the moral upperhand, for it doesn’t pretend to be serving some larger purpose.

Like science fiction, serial killers twist our values on their head and allow us to reflect back on ourselves — What would happen if our planet had two suns instead of one? Or if we communicated through telepathy? — and, in the case of serial killers — what if you didn’t care if you killed someone? Or took pleasure in the killing? Serial killers are big business. Their psychological profiles and crafty, nefarious plotting can be patiently examined in a television series like Dexter or Bates Motel and people will watch them.

Only after I read the news about the discovery did I realize how long I had suppressed even thinking about the murder. For two decades, I now realized, I had been holding my breath as we drove along the road past the golf course; and all that time the head loomed spectral and ghoulish in the crenellations of my mind.

The New Jersey State Police managed to trace Heidi Balch’s identity by searching records of prostitution offenses at the time. If my consciousness was first shattered in 1989 when they found the head, it was this fact that shattered it again. Heidi Balch was killed because she had been pushed, by will or by circumstance, to the margins of our society to the extent that her very livelihood was a criminal act. Rifkin, Dahmer, and Gacy preyed on the weak and marginalized. It’s hard to imagine a sober conversation about legalizing prostitution in America today or empowering sex workers with rights, especially when abortion laws are becoming still more restrictive. Heidi Balch was unclaimed and nameless for 24 years. Now we know her name, but if she were alive today what would prevent us from forgetting her again?

Image Credit: Weekly World News, May 23, 1989.