1.

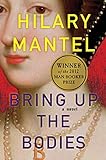

The modern world swooned last month when the bones found under a parking lot in Leicester, England were confirmed to be indeed those of Richard III. Part of the fuss was due to the wonderfully incongruous image of a 15th century king entombed under this age’s most banal and omnipresent architectural fixture — “What’s under my parking lot?” we mused breathlessly. And, to be sure, Anglophilia is ascendant in these tremulous days of “Downton” and Hilary Mantel’s fittingly titled historical novel Bring Up the Bodies. But the real business with the skeleton of course had to do with Richard’s status as a hated historical king, the deformed, dissembling, and nephew-smothering arch-bad guy whose downfall mercifully concluded the grisly War of the Roses.

The modern world swooned last month when the bones found under a parking lot in Leicester, England were confirmed to be indeed those of Richard III. Part of the fuss was due to the wonderfully incongruous image of a 15th century king entombed under this age’s most banal and omnipresent architectural fixture — “What’s under my parking lot?” we mused breathlessly. And, to be sure, Anglophilia is ascendant in these tremulous days of “Downton” and Hilary Mantel’s fittingly titled historical novel Bring Up the Bodies. But the real business with the skeleton of course had to do with Richard’s status as a hated historical king, the deformed, dissembling, and nephew-smothering arch-bad guy whose downfall mercifully concluded the grisly War of the Roses.

It’s more or less agreed among people who take the time to review these things that Richard was the target of a posthumous smear campaign orchestrated by the triumphant Tudor dynasty (whose founder Henry VII defeated Richard in 1485). Official Tudor chroniclers during the mid-16th century purposefully blackened Richard’s character, and Shakespeare followed suit by putting a hunchbacked tyrant on stage in the electrically charged history, The Tragedy of King Richard The Third. Rightly or wrongly, Richard went down in history as a regal punching bag, a ruler who embodied the worst of late-medieval chicanery.

It’s more or less agreed among people who take the time to review these things that Richard was the target of a posthumous smear campaign orchestrated by the triumphant Tudor dynasty (whose founder Henry VII defeated Richard in 1485). Official Tudor chroniclers during the mid-16th century purposefully blackened Richard’s character, and Shakespeare followed suit by putting a hunchbacked tyrant on stage in the electrically charged history, The Tragedy of King Richard The Third. Rightly or wrongly, Richard went down in history as a regal punching bag, a ruler who embodied the worst of late-medieval chicanery.

But now, with even the American media reporting at fever pitch on the miraculous discovery, the contested reburial plans, and digital facial renderings (evidently, Richard III resembled Shrek’s Lord Farquaad), it appears that England’s most reviled king may just get a reappraisal. Richard’s apologists hope that his newfound celebrity will encourage us all to submit our old Shakespearean prejudices to a round of honest fact-checking. It’s a simple procedure, in which historical evidence is marshaled to root out the mythology inherent in literary representation, to the point where the literary work in question can be dismissed as little more than myth itself.

The technique has its fair uses — we might be grateful for it when dealing with, say, Kipling’s odes to imperialism. But its corollary is nearly always the driving of a wedge between art and history, two disciplines, we are admonished, that best not consort with one another. Already we can see the process at work with Richard III. Even Harold Bloom, high priest of American Bardolatry, recently averred in Newsweek that “Shakespeare’s ironic, self-delighting, witty hero-villain has a troubling relation to actual history.” This is defensible enough, yet we should remember that there is no corrective for propaganda like a reader’s awareness thereof. If we arm ourselves with this knowledge, Shakespeare’s art can yield deeper, more illuminating insights into Richard’s life and times than we might imagine. However, if we divorce Richard III from the “actual history” we are insensitive to literature and, worse, we weaken our own understanding of monarchy, power, and history itself.

2.

In Shakespeare we encounter Richard III as an evil genius, one theatric-evolutionary step beyond the Vice character of medieval morality plays. Richard deceives and beguiles his way to the crown, killing off his rivals and then his friends until he has only ghosts to attend him. There is a clear logical schema for all this hell raising: the man is a monster, a hideous swamp-world creature, “Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time / Into this breathing world scarce half made up.” His monstrosity served him in wartime, yet now civil conflict has given way to stable Yorkist supremacy under his brother Edward IV, and the bellicose Richard finds himself without suitable vocation. The weapons have been hung up on the walls, and the lutes come down for seduction and other trifles of peace. “Since I cannot prove a lover / I am determined to prove a villain,” Richard intones, and that’s that.

And yet Shakespeare just doesn’t come sans complication. Richard is too clever a thespian, too candid a soliloquist, and, belatedly, too tormented by conscience to lose all title to sympathy from the audience. He is too conflicted and desperate in his final scenes to bunk amicably with Iago in the prison of Shakespearean opprobrium — Iago who, like a mischievous alien beamed down to Venice exclusively to fuck with Othello, just sort of shuts down after Desdemona is murdered. In fact, Richard’s near-remorse on the eve of the fatal Battle of Bosworth Field provides material for some of the most contorted, dialogic, and self-conscious lines in the Complete Works. After a night of visitations from the ghosts of his victims, a frightened Richard “Starteth up out of a dream”:

What do I fear? Myself? There’s none else by.

Richard loves Richard; that is, I am I.

Is there a murderer here? No. Yes, I am.

Then fly. What, from myself? Great reason why:

Lest I revenge. What, myself upon myself?

…Alas, I rather hate myself

For hateful deeds committed by myself!

I am a villain. Yet I lie, I am not.

Fool, of thyself speak well. Fool, do not flatter.

What happened to the cool calculation and protean slipperiness of the old sly Richard? Whence this fabulously split subject, marooned by his own malfeasance? This Richard improbably presages the dazzling self-doubt of Gerard Manley Hopkins, the late-19th-century disconsolate and poet of brooding, rhyme-packed, sprung-rhythm verse. Turns out this most detestable of English kings, killer of little boys, and bane of decent folk everywhere also clutches that thing Hamlet purports to have, “that within which passes show,” a deeper interiority, a nagging conscience, an ego turned on itself. And yet Richard, like a good schoolboy intent on completing an assignment, has proved a villain. So why does he quake?

The pith of the tale, for modern viewers at least, is that even as Richard proves a villain, he disproves the concept of pure villainy — at the end of the day, a much more consequential disproof than proof. The question at hand is not whether Richard kills people, rides roughshod over morality, or perversely revels in doing so. The problem for us — we distant modern viewers who have seen so many kings come and go in these history plays — is that as soon as Richard affixes the label of villainy to himself the label starts to lose its distinction, to melt into the milieu of political violence.

3.

The other part of the “story” in the exhumation of Richard III — the interest over and beyond monarchic infatuation and historical import — also had to do with our abiding lust for proof. This time it came not from Tudor ideology but from the de-politicized precincts of scientific empiricism. And what proof: the identity of the bones of Richard the Third has been settled in a bravura display of genetic testing, radiocarbon dating, and advanced anthropological sleuthing. Mitochondrial DNA found in a tooth pulled from Richard’s jaw matches mitochondrial DNA of two descendants of his sister, one Michael Ibsen, furniture maker of London, and a second anonymous relation.

As the story broke I joined the multitudes of media viewers in satiating my curiosity and awe. I read the articles, gaped at the curved spine, scrutinized the nasty blow to the head. I went on YouTube and found the videos produced by the University of Leicester detailing all of the digging, extracting, and testing done to get to the elusive bones, and then to their precious DNA cargo. Suddenly Richard III became a marvel of scientific certitude, a job-well-done of today’s sophisticated epistemological techniques. Now we know.

“What do we know? Know Richard? There’s none else by…” So the bones are Richard’s. As he might have said, “I am I.” But the tautology does us as much good as it did the roles’ first interpreter, Richard Burbage, when he declared it before an Elizabethan audience. It was as if the moment Richard’s mortal remains hit the Internet, he ceased to be a villain or a politician and became merely a curiosity, stripped of intrigue or depth, a subject of pop historian enthusiasm.

To be sure, it was a banner day for the Richard III Society, the organization which, since 1924, has dedicated itself to promoting a rehabilitated Richard. Members of the group, which as it happens is patronized by the current Duke of Gloucester, raised $250,000 to support the search for Richard’s grave and his genetic testing. It was money well spent. As one organizer told the New York Times, “Now we can rebury him with honor, and we can rebury him as a king.” This defanged, refurbished king was a civic-minded administrator who improved the commons’ channels for airing grievances and lifted bans on printing. His violence was understandable given the times. As for the young princes in the Tower — who really knows what happened.

We all want to be remembered well, and that’s a hard proposition when you die on the losing side of bitter dynastic struggle. The Richard III Society may be correct in asserting that Richard was vilified without substantial proof. There is proof Richard did enact some nice, forward-thinking policies — as solid proof that the parking lot bones once fit together to form Richard’s scoliotic frame. But there’s something meretricious, or perhaps just distracting, about the whole question of proof in this case. If Richard wasn’t as bad as we think he is, there also seems to be no need to truly pal around with his ghost. To invoke a touchstone of modern political affability, Richard probably wasn’t a guy you’d want to have a beer with, a power-hungry warlord at best. And it remains likely that much of the evidence that would prove or disprove Richard’s rotten reputation has been lost.

That’s no reason to gag Richard’s supporters — let them toast to their gallant White Boar if they want — but the lessons worth drawing from the whole business are too important to be lost in the penumbras of medieval recordkeeping or the weirdness of historical fanclubs. This is true especially when the crux of the lesson can be found in Shakespeare’s plays. By this I mean that, besides celebrating the Tudor ascension, Richard III and the other history plays demonstrate time and again the precarity, anxieties, and senselessness of the whole monarchical enterprise. No one belongs on the throne, not Richard and not Henry Tudor, but each must believe he does. Thus, it’s not that Richard III is so off the mark in representing the spirit of its subject. Rather, the great falsehood, deeply rooted and insidious to this day, is the belief that all the other players in the sordid history were so dissimilar from the scheming Duke of Gloucester. The theatrical Richard’s manic fear of self-harm (“Lest I revenge. What, myself upon myself?”) bespeaks the big idea here: his violence is selfsame with a larger violence, a culture of conflict that will undo him.

Thus, a fascinating paradox is at work in Richard III, one with far-reaching implications for our notions about the proper relationship between art and history. It so happens that a piece of literature drenched in historical revisionism nonetheless captures Richard’s zeitgeist with impressive moral and political clarity. Our own pop-historical gaze seems downright blurry by contrast. How can this be? It seems the paradox is an effect of repression: due to our liberalist preference for transparency, information, and empiricism, we refuse to peddle in political myths. But our romance with regalia suggests their attractiveness; we maintain an unacknowledged appetite for a power system whose very structure rests upon the myth and spectacle of an unverifiable claim to kingship.

Shakespeare’s art, on the other hand, luxuriates in this kind of myth. Writing centuries later about Dostoevsky, the critic Mikhail Bakhtin described how the great Russian novelist transformed the monologic “idea” into the living “image of an idea,” the irreducible dialogue that composes a single idea. This is precisely the mechanism of Richard III, a dramatic work that is not interested in dispelling myths, but rather in giving them life, and then subjecting them to the logical pressures of experience. Long before Richard’s bones were exhumed and his identity finally proven, Shakespeare had already unearthed from the pit of Richard’s soul the essence of his character, the self-contradiction of his idea: “Is there a murderer here?” No/Yes. It’s not villainy, it’s politics: monarchic despotism that sanctions horrific violence. It’s the stuff of kingship, and it’s still going on. The embattled Bashar Al-Assad is, after all, a king in trouble too. He might pause to think on Richard.

Image via Wikipedia